He was our Kenneth

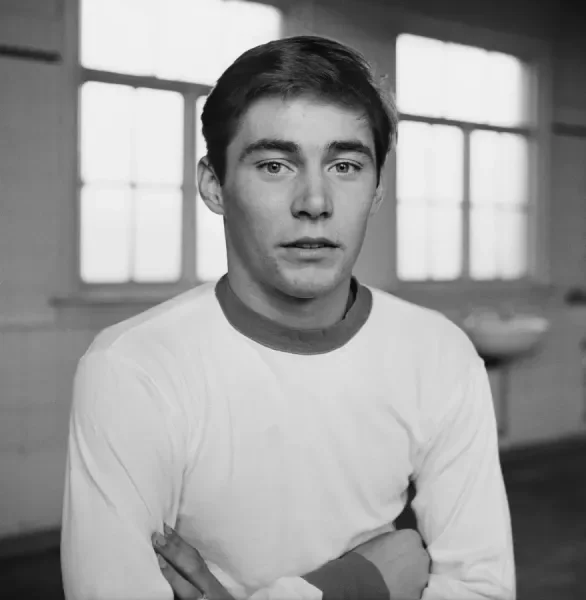

Ken at Aston Villa

Part One: Copley

Copley, 1947

He was born Kenneth Morton on 19 May 1947.

No middle name.

At home, Eddie and Edna called him Kenneth. Outside the house, particularly in the North East of England, he was Kenny.

He was our Kenneth.

Copley was small. One road through the village. Farmhouses set back off the lane. From the very top to the very bottom, barely a kilometre. Quiet enough that you noticed sound when it arrived.

When Ken talks about it now, he says it reminds him of All Creatures Great and Small. That same sense of countryside calm, of people knowing one another, of space to roam.

Sundays were special. Copley Sunday meant picnics, family together and football on any bit of grass that would allow it. Cousins were there. Neville and John Chapman. Neville would later play for Middlesbrough, but back then he was just older, fitter, someone to chase in the summer holidays.

Copley felt safe. Friendly. A farming community where people said hello, where they noticed if you didn’t have your ball with you. There were only one or two shops at first, a Co-op later. A handful of council houses. Not many children. Five-a-side or six-a-side at most. If the ball went over a wall, nobody complained.

Ken was an only child. Well looked after. Well cared for.

He was born in a terraced house, two or three in a row of five. There was a yard and across the driveway a patch of grass. Enough space to juggle, to practise, to wear the ground down. To have a kick without troubling anyone.

Eddie was a busy man. He ran a garage and helped the local farmers. Edna was kind and loving. Like most households of the time, it was disciplined and structured, but Ken never got into trouble. He was always playing football.

Their first house had a backyard. Over the lane was an allotment. That became another place to play. When they later moved to Copley Lane, there was a hot bath ready when he came home muddy and tired. Boots left at the back door. Football was never discouraged. It was simply part of life.

Ken remembers Auntie Effie and Auntie Gwenie, his aunties by marriage. Gwenie was a Sunderland supporter, so football talk and football history were always around. His dad was friendly with Gordon Coe, president of Evenwood Town Football Club. At the time, the club was bringing players in from the army barracks and Eddie spent a lot of time driving and picking them up. Football, again, was just there. Woven in.

One of Ken’s earliest football memories has never left him.

He would have been eight or younger, at a match between Evenwood and Bishop Auckland. The legendary Bob Hardisty was carrying the ball out of defence when Ken ran under the wooden barrier and took it cleanly off him.

He didn’t get into trouble. The Evenwood crowd applauded. Bishop Auckland supporters were less impressed, the tackle stopping the start of an attack. Hardisty looked shocked, then smiled. Ken remembers him coming over afterwards and shaking his hand.

He doesn’t think his dad was with him that day. He thinks he was on his own.

Football never arrived in Ken’s life. It was always there.

Other boys went to the beck, the stream that ran nearby, or into the woods. Ken went with the ball. Always with the ball. He can’t remember getting his first one, only that he always had one.

After school was his favourite time of day. Three o’clock. Dribbling in and out of the white lines painted on the road home, then straight up to the recreation ground. He walked to school every day, ball under his arm, even though there was a bus.

Breakfast was simple. Cornflakes. His favourite meal was beans on toast. Still is.

Winters could be harsh. Snow covered the roads. His dad would clear them with the plough, and Ken would jog behind it on the way to school. If the driveway was blocked, it was cleared so he could have a kick. Weather rarely stopped him.

He wore sandshoes most days, boots for football. They weren’t brilliant. Wet Saturdays were just Saturdays in the North of England. The sound of the ball on stone walls was a dull thud. His mother always knew where he was.

If he couldn’t get out, he read. Football annuals. Football cards. Licking his fingers to turn the pages while waiting for the chance to play again.

Television was black and white. Match of the Day on Saturday nights showed him new things. Different goals. Players running with the ball. Diving headers. The next day he would be out practising what he’d seen, alone if necessary, becoming Tom Finney or Stanley Matthews in his own mind.

He was good at other sports. Decent at cricket. A strong tennis player. A very good athlete. He won the 100, 200 and 400 yards at school. But none of it competed with football.

While other boys his age played in the woods, Ken, six or seven years old, played football with older boys at the rec. He was always challenged. Losing taught him resilience. When something went wrong, he worked harder. Got the ball out and battered it against the wall until it felt right again.

He didn’t talk much on the pitch. He let his football do the talking. He wasn’t a bragger. He was loved in the village. People noticed him without making a fuss.

He was never lonely. There was always a ball.

Looking back now, he says football was everything to him.

“If I look at it now,” he says, “it was like a marriage.”

When asked where home feels like now, he says it’s where we live today. But when we watch English television and he sees a village, a lane, a patch of countryside, he still says, smiling, just like Copley.

Copley gave him space.

Family gave him security.

Football gave him direction.

This is where the story begins.