Governance + Politics

If I were President

This is also a daydream.

Not a campaign.

Not a pitch.

Just an exploration of what leadership at the top of the game could look like if it were grounded in football, not status.

The President does not run football day to day.

But they shape what the organisation stands for, what behaviour is normal and what is quietly tolerated.

That matters more than most people realise.

The role is not ceremonial

The President is not there simply to attend functions and smile for photos.

The President sets the moral and cultural tone of the organisation. What they say yes to, what they stay silent on and what they challenge tells everyone else what is acceptable.

I would see the role as stewardship, not prestige.

This game was here before me. It will be here after me. My job would be to leave it healthier, calmer and more stable than I found it.

The governing body exists because its members exist

A football governing body can sometimes begin to feel like the centre of the game.

It is not.

It exists because clubs and associations exist.

It exists because volunteers give their time.

It exists because children play, parents drive, coaches coach and communities care.

Without that, there is no organisation to govern.

Authority in football is not ownership. It is stewardship on behalf of members.

That means listening matters.

Respect matters.

Partnership matters.

Clubs and associations are not there to serve the governing body. The governing body exists to serve the game they are already delivering.

Associations and clubs are the engine room

Junior associations and community clubs are not peripheral parts of football.

They are the engine room of the game.

They are where players begin, where families connect, where volunteers learn leadership and where the next generation of football people is formed.

Every senior player, coach, referee and administrator starts somewhere. Almost always, it is in an association or a community club.

If those structures weaken, the whole system weakens. Not immediately, but inevitably.

Support does not only mean funding. It means clarity. Stability. Realistic expectations. Systems that recognise most of the work is done by volunteers.

What happens there today determines what football looks like in ten and twenty years.

Children’s safety and joy come first

At its heart, football is a children’s activity.

If children are not safe, if they are not having fun, if they are not treated with respect, then nothing else we build matters.

Safeguarding is not a compliance box. It is culture.

I would speak about child safety openly and often.

I would expect safeguarding to be properly resourced.

I would support strong, clear processes when issues arise, even when they are uncomfortable.

Safeguarding must have authority, independence and proper resourcing, not just policy documents.

But safety is only half the picture.

Football must also be joyful.

If the environment becomes too adult, too political or too pressured, we forget who the game is for. Children stay in sport when it is fun, when they feel they belong and when adults behave like role models.

Participation is not sustained by structures alone.

It is sustained by experience.

Protecting the game from ego

Football politics attracts strong personalities. Ambition. Territory. History. Grievances.

The President cannot add to that noise.

I would work to lower the temperature, not raise it. To defuse, not inflame. To bring conversations back to what is best for football when they drift toward who wins.

Not every disagreement needs to become a battle.

Not every slight needs to be remembered forever.

Backing the CEO and challenging in private

The President and CEO relationship sets the tone for the whole organisation.

Public undermining weakens the organisation. Blind loyalty weakens it too.

I would support the CEO in public, but behind closed doors I would ask hard questions. Are we listening. Are we overloading volunteers. Are we solving problems or just managing optics.

The President’s job is not to run operations.

It is to ensure the person who does is supported and properly challenged.

Keeping the Board grounded

Boards can drift upward into governance language, risk registers and strategy documents.

All important. None of it the game itself.

I would constantly bring the focus back down.

Clubs.

Associations.

Volunteers.

Children playing on cold mornings.

If a decision makes life harder for the people actually delivering football, we should know that before we vote, not after.

The President also has a practical role here, ensuring Board meetings are disciplined, agendas are clear and decisions are followed through. Good governance is not just what is discussed, but how the Board functions.

Making culture a governance issue

Culture is not soft. It is structural.

If volunteers feel disrespected, if clubs feel unheard, if junior football feels invisible, that is not a communications issue. That is a governance failure.

I would ask regularly

Do clubs trust us

Do associations feel supported

Do volunteers feel the load getting lighter or heavier

Those answers matter as much as financial reports.

Culture is also about behaviour standards. Respect for referees, volunteers and each other cannot be optional. The President can help set the expectation that how we behave is as important as what we achieve.

Normalising transparency about conflicts

In a small football state, everyone has connections.

Pretending conflicts do not exist is theatre.

I would set the expectation that interests are declared calmly and routinely. No embarrassment. No drama. Just honest governance.

Trust grows when reality is acknowledged.

Stability over constant reinvention

Boards often want to leave a mark.

Sometimes the bravest decision is not to change things.

Football people can handle hard seasons. What they struggle with is endless structural churn.

Stability allows clubs and volunteers to plan, recover and build properly.

Volunteer impact matters

Before approving new requirements, systems or reporting, I would ask

Who is doing this work

And when

Usually the answer is a volunteer, late at night.

If we are not reducing load somewhere else, we are quietly burning people out.

Being a visible advocate for football

The President should not be silent outside boardrooms.

Football needs a public voice.

I would speak up when football is overlooked.

When it is misunderstood.

When it is unfairly diminished.

Not combatively. But clearly and consistently.

Advocacy is also about steady relationships. The President helps maintain constructive, ongoing dialogue with councils and government so football is represented early, not only when issues arise.

Promoting the game, not just the organisation

I would be visible at grounds.

Visible in conversations about facilities.

Visible when football needs representation.

If football people only see their President at formal events, the role feels distant. If they see them occasionally on the fence at ordinary matches, the role feels connected to reality.

Defending football without apology

Football sometimes carries an unnecessary defensive tone.

I would speak about football as a major sport, a community builder and a global game that belongs here.

Pride in the game is not arrogance. It is leadership.

Keeping the long view

CEOs think in seasons and budgets. Boards think in terms.

The President has to think in decades.

How does this affect football in ten years.

Will this leave the system stronger or just quieter for now.

Being a bridge in times of tension

Football always has fault lines. Metro and regional. Junior and senior. Elite and community.

The President cannot remove these tensions. But they can prevent them becoming fractures.

Leadership sometimes means helping different parts of the game understand each other, not just argue past each other.

Protecting fairness and process

Trust in football depends on people believing processes are fair and independent.

The President helps ensure that complaints, disciplinary matters and decision-making pathways are clear, consistent and free from influence. Fair process protects people and it protects the game.

Remembering leadership is temporary

Power in sport can become sticky.

No one is indispensable.

Part of the role is preparing others, encouraging new leaders and ensuring the organisation is not dependent on one personality. That includes actively mentoring future leaders and ensuring governance knowledge is passed on, not lost when individuals step away.

Healthy systems outlast individuals.

And yes, I would care

Not about status.

Not about titles.

About the game.

About the people who give their time to it.

About the kids who just want to play.

Care is what stops decisions being made purely for optics or politics.

The bigger picture

The President cannot fix everything.

But they shape the environment in which everything happens.

They help decide whether football feels political and heavy, or stable and supported.

That influence is quiet, but it is enormous.

All This, So We Can Play 90 Minutes on a Saturday - NPL Transfer Window

What You Don’t See on a Team Sheet

Every week people see names.

Who is in.

Who is out.

Who signed.

Who didn’t.

What they don’t see is the regulatory machinery sitting behind those names.

And during a transfer window, that machinery is running at full speed.

Our NPL transfer window closes at 5pm on Tuesday 10 February. To most people, that sounds like a football date. To clubs, it is a compliance deadline.

Football loves an acronym, and there are plenty in this space. I’ve included a simple glossary at the bottom if any of the terms are unfamiliar.

The Forest, Not Just the Trees

At NPL level in Tasmania, a club is not just picking players.

It is operating inside a layered governance system.

At the top sits FIFA. That’s where international transfer rules and player status definitions live. If a player has previously been registered overseas, international clearance is required. No clearance, no registration.

Below that is Football Australia. They apply FIFA regulations here and add national ones. That includes the National Registration, Status and Transfer Regulations, prescribed professional contracts, and the Domestic Transfer Matching System (DTMS). Even a domestic move involving a professional player can sit inside a FIFA-based transfer platform.

Then comes Football Tasmania. Here is where squad construction rules apply. Player Roster Principles (PRPs). Squad size limits. Visa limits. Goalkeeper nationality restrictions. Age eligibility rules. These are not suggestions. They are compliance requirements.

And then there are the competition rules. Match sheets. Registration categories. Technical area identification. Match day requirements. Media and signage obligations. A player can be legally registered but still ineligible if these layers are not met.

All of this must line up before kickoff.

A System That Evolved - The Player Points System

For many years, NPL clubs operated under the Player Points System (PPS).

Instead of just saying “name 23 players,” the PPS gave each player a points value based on experience, background and playing history. Clubs had to build a squad that stayed under a total points cap.

It was designed to prevent wealthy clubs stacking experienced players, protect competitive balance and encourage youth development. In practice, it meant constant calculations, classifications, and discussions about how players were categorised.

I can remember sitting around the table trying to work out when a player first played for us. What counted. What didn’t. What it meant if they had left for a year, like Nick my step son did when he signed for Melbourne City. Did that change their category? Their points? Their status? Their loyalty? There was a lot of memory involved in that system.

That system has now moved to Player Roster Principles (PRPs). Instead of a numerical points cap, PRPs focus on roster structure — squad size, visa limits, youth eligibility and similar controls. The aim is still competitive balance and development, but the mechanism has changed.

Different system. Same compliance layer.

The Transfer Window Is When It Compresses

A transfer window is not just a period to sign players.

It is a deadline for contracts to be completed, statuses to be correctly classified, documents to be lodged, systems to match information between clubs, registrations to be approved and clearances to be received.

If a player is classified as professional, that triggers a different set of obligations. Prescribed contracts. Additional documentation. DTMS processes. It is not just ticking a different box.

If a player has played overseas, there may be an international clearance in another time zone, in another federation, on another schedule. (ITC)

And all of this is happening while coaches are training, players are asking questions, and matches are approaching.

This Isn’t Just “Typing Names In”

At this level, football admin sits inside global rules, national regulations, state roster controls and competition operations.

Each player is a small compliance project.

One contract.

One status decision.

One registration.

Possibly one DTMS process.

Possibly one international clearance.

One roster inclusion.

Multiply that by a squad.

Thank goodness this isn’t my area of expertise. We are incredibly lucky to have Rick, our Registrar, who actually understands this world. Every club has someone like Rick - the quiet expert making sure the paperwork matches the rules so players can actually play.

Why It Exists

There are good reasons for this structure.

Fair competition.

Player protection.

Youth development pathways.

International order in a global game.

But the work required to satisfy that structure lands at club level. Often on volunteers or people already wearing several hats.

When a Name Appears - or Doesn’t

Sometimes a player isn’t missing because a coach changed their mind.

Sometimes they are waiting on a clearance.

Or a system step.

Or a document.

Or an approval.

That part isn’t visible from the sideline.

But it is very real.

All of this governance, paperwork, systems and approvals - across FIFA, national rules, state regulations and competition requirements - sits there quietly in the background.

All so a group of people can legally play 90 minutes of football on a Saturday.

That’s the bit most people see.

The rest is the invisible work that makes it happen.

Glossary — Football’s Favourite Acronyms

FIFA – World governing body of football.

FA (Football Australia) – National governing body for football in Australia.

TMS – Transfer Matching System used for international transfers.

DTMS – Domestic Transfer Matching System for professional player movements within Australia.

NRSTR – National Registration, Status and Transfer Regulations.

PRP – Player Roster Principles governing squad construction.

PPS – Player Points System, the previous NPL squad control model using a points cap.

NPL – National Premier Leagues competition tier.

ITC – International Transfer Certificate for international clearance.

DTC – Domestic Transfer Certificate generated in DTMS.

DRIBL – Match day team sheet and match data system.

Play Football – National online player registration platform.

AFC / OFC – Asian and Oceania Football Confederations (visa player category).

This Little Blog Has Turned Into Something Much Bigger Than Me

Ken and I at Spurs stadium in October. Yes, they were playing NFL there.

When I stepped down from the presidency at South Hobart, I felt a shift.

For years I had carried responsibility. Every word mattered. Every opinion had weight. There were things I thought but could not say. Things I saw but had to hold back on. That is part of leadership.

Stepping aside did not mean I stopped caring.

It meant I finally had space to think out loud.

And to say some of the things that had lived quietly in my head for years.

This blog started in that space.

It was not a strategy. It was not a plan. It was simply a place to put the football thoughts that had nowhere to go anymore.

It has become something much bigger.

A new chapter I didn’t see coming

My first post went up on 8 December.

Since then, 2.9K people have visited the website, with more than 5.1K post views.

That honestly blows me away.

I did not start this to build numbers. I started it because my head was still full of football. Stories. Ideas. Frustrations. Memories. Questions.

Writing gave all of that somewhere to go.

What I did not expect was how much I would love the process.

Why I knew people were interested

I had a hint that people cared about football stories long before this blog took off.

For years I had a little hobby of taking photos at games. Training. Sidelines. Celebrations. Moments that might seem small but mean everything to the people involved.

I uploaded them to Flickr simply to store and share them.

Over two years those photos have had 4.2 million views.

That was not one viral moment. That was steady interest from people who care. Parents. Players. Coaches. Friends. Local football people looking for faces, memories and moments.

It told me something important. People want to see and remember this game in all its detail.

And yes, I am quite sure at least 100K of those views were Ken.

Learning something completely new

I built the website myself on Squarespace.

That sentence still makes me laugh.

A few months ago I would not have known where to even start. There were moments I felt slow, frustrated and completely out of my depth.

But I stuck at it.

I learned about structure. Headings. Flow. How to shape a piece so it actually says what I mean, not just what falls out first. I draft, then amend, then rethink, then craft again.

And yes, I had help.

ChatGPT has been like a patient tutor sitting beside me. It helped me understand writing structure, think through ideas, check my flow, and sometimes do research that sent my brain off in new directions. I regularly remind it that NZ grammar and spelling matter to me. Yes, I was born in New Zealand.

But the stories, the opinions and the experiences are mine. The words come from my life in football. This tool helped me learn how to shape them.

It stimulates my thinking. It keeps me energised. It gives my football brain a place to work.

The people who said yes

A special thank you to the football people who have said yes to being interviewed.

That generosity matters more than you might realise.

When someone shares their story, their pathway, their doubts, their memories, it changes how we see them. The coach on the sideline is no longer just the coach. The referee is not just a whistle. The volunteer is not just a name on a committee list.

They are people with history, setbacks, turning points, family influences and moments that shaped them.

I have about ten interviews from all around the state on the go right now, so keep an eye out for more football people and their lives on and off the field.

The people behind the scenes

A big thank you to Nikki, who so generously arranges the photos with each interviewee and then travels around to take their portrait.

Her care and patience add another layer to these stories. A face, a moment, a presence that brings each piece to life.

She often sends the photo through with a little note like, “What a nice bloke,” or, “I took so many photos and they were all great, he takes a great photo.” Those small comments say a lot. They remind me that these are not just interviews. They are people, and good ones.

A thank you as well to Matthew Rhodes for allowing me to share the interviews on Tassie Football Central. That helps these stories reach further than my own little corner of the internet, and gives Tasmanian football people the visibility they deserve.

What people are actually reading

It has been interesting to see what has resonated most so far.

The Stop Telling Football People to Be Grateful series, especially Part 3, OMG the Money, has been widely read as has “If I were the CEO”.

And the interviews.

Hundreds of people are reading those conversations with football people from all parts of the game. That tells me something important. People do not just want scores and ladders. They want context. They want to understand the people inside the game.

I am also learning that Facebook likes do not necessarily translate into blog posts being read. The quieter numbers, the people who actually click through and spend time reading, tell a much more meaningful story. For example 700 people have read James Sherman’s interview so far.

A small apology

If you have struggled to find posts by category lately, that is a Squarespace issue, not me.

They have said they are working on it. Hopefully it is fixed soon.

Keep the ideas coming

If there is a person, story or topic you think should be covered, please use the contact page and let me know.

This space is growing because football people keep giving me things to think about.

This blog might have started as something for me.

But it is very clearly becoming something for the football community too.

And that is the best outcome I could have hoped for.

Thank you for reading.

From Preston Streets to Tasmanian Touchlines

Jon Fenech photographed by Nikki Long

An interview with Jon Fenech, Sporting Director and NPL Men’s Head Coach, Kingborough Lions United

Some football journeys are planned.

Some just never really stop.

When you speak with Jon Fenech, you get the sense his path into coaching in Tasmania is simply the latest chapter in a life where football has always been present, shaping decisions long before they looked like decisions.

Growing up in football

Jon grew up in Preston in the north-west of England, with a Maltese father and British mother. Football was everyday life. Streets, parks, local pitches on weekends, usually with his dad and brother.

At 13 he was scouted by Blackpool Football Club and joined their academy, later becoming a young professional. At 17 he represented the Malta national football team at youth international level.

His journey then took him through Malta and southern Europe before returning to the UK to complete a Business and Economics degree at Durham University, playing semi-professionally alongside study.

One memory still sits high. Watching Roberto Baggio at the 1994 FIFA World Cup, sitting with family and watching his father ride every emotion as an Italy supporter. That moment cemented his love for the game, not just the football itself, but what it means inside families and across generations.

He later moved to Brisbane to help grow a property recruitment business with a university friend, while staying involved in football through playing and coaching in the lower leagues in Queensland. Football never really left. It simply shifted shape.

From player to coach

Jon began his coaching badges while still playing. As injuries and life commitments increased, he realised he could no longer give playing what it demanded.

Friends working at the highest levels of the professional game encouraged him back into football through coaching. That shift allowed him to combine leadership and management skills from business with his first love, football. He has always enjoyed analysing the game and helping players improve. Coaching felt like a natural evolution rather than a replacement.

Life beyond the pitch

There is, by his own admission, not much time outside football.

Alongside his role at Kingborough Lions United Football Club, Jon is completing a postgraduate degree in football management and sporting directorship through the Professional Footballers' Association, and has recently started his A Licence with the Asian Football Confederation.

Any spare time is spent with his daughter, and thanks to her, he has developed a surprising passion for jigsaw puzzles.

Coaching philosophy

Forward. Outwork. Together.

That is how Jon sums it up. Attack with intent, outwork the opposition and compete as one team. For him, progressing and creating matters more than playing safe. It is a mindset as much as a tactic.

His three non-negotiables sit clearly underneath that.

Courage to play forward, because growth requires risk and a willingness to take the game on.

Honest work rate, meaning effort, reactions and discipline in every moment, not just when things are going well.

Team-first behaviour, where decisions and standards must serve the group, not individuals.

At their best, his teams are high-energy and proactive. They press aggressively when appropriate, attack with speed and intent, and fight for each other in every moment of the game. What he describes is not only a style of play, but a behavioural standard that runs through the group.

Why Tasmania, why now

Jon describes his move as the right leap at the right time. He had built a corporate career he genuinely enjoyed and was proud of and left a great company in capable hands, but it felt like the moment to try something new.

When the opportunity arose at Kingborough Lions United Football Club, it immediately felt right. From his first conversations and time spent around the facilities, he saw a club committed to building something sustainable. Not just chasing short-term success, but creating a long-term future for players and the community. He also notes he is fortunate to have excellent facilities at Kingborough, even while recognising the broader challenges across the state.

Tasmania itself stood out. He talks about a strong football community, passionate people, and real potential. On any given weekend you see people from different clubs turning up to watch other games, catching up in clubrooms and supporting the game beyond their own team. That sense of connection is something he believes is not always present in bigger football markets.

What surprised him

One of the most pleasant surprises since arriving has been that connectedness. Junior nights at the club. Match days where familiar faces keep turning up across different grounds.

He was also struck by the scale and speed of change. Tasmanian football is moving quickly from community participation models towards demands for performance pathways, which are still very limited. Clubs are growing. Facilities are improving. Operational demands are increasing. Yet much of the work is still carried by volunteers and overstretched staff. The ambition is strong. The infrastructure and systems are still catching up.

And still, cold winter nights, lights on, a handful of people in jackets along the fence and great football moments. Environment is not just facilities, it is people.

Where Tasmania falls behind

Infrastructure depth is the biggest gap. Facilities, pitch availability and training environments are under pressure as demand at junior and youth level rises rapidly.

Operational systems are another challenge. Many clubs are still transitioning from volunteer-run models to more professional operations, which are far more established in Queensland and the UK.

There is also inconsistency in development environments. Not every player trains within a structured pathway. For Jon, this is not about talent. It is about systems, volume, and environment quality.

How Tas teams compare nationally

When asked how Tasmanian teams would translate into other competitions, Jon does not focus first on talent. He focuses on environment.

He believes a mid-table Tasmanian NPL side would likely compete in FQPL 1 in Queensland, while the top Tasmanian teams would compete in NPL Queensland. The difference, in his view, is not simply ability. It is squad depth, professionalism and the ability to maintain standards across a long, demanding season.

For Jon, it is not about the best eleven players. It is about the environment that supports them week after week.

The biggest myth

Jon believes the biggest myth Tasmanian football tells itself is that it is further behind than it actually is. That belief, he says, limits ambition before the work even begins.

In his view, Tasmania has the quality to aim higher, but it needs to start building with national relevance in mind rather than constantly comparing itself from a position of deficit. For Jon, mindset is part of the system, not separate from it.

Coaching in Tasmania

There are some very strong coaches operating at senior NPL and WSL level. The biggest opportunity lies in youth and women’s football, where coaching is often volunteer-led and knowledge does not always filter consistently down from senior environments.

Coaching is strongest where clubs have clear structures and alignment between youth and senior football. It is weakest where coaching is disconnected from club-wide planning and environments remain purely participation-driven without development frameworks.

Better support for grassroots coaches, male and female, is a key step. Jon adds that he would love to appoint more female coaches at Kingborough, but finding them is the hardest point.

Coach education, Jon says, should be about standards, not labels. He speaks positively about the work of David Smith and Football Tasmania, but believes real development happens beyond certificates, through workshops, mentoring, collaboration and shared learning environments. The best coaches never stop learning.

What governing bodies should focus on

Jon believes Football Tasmania should increasingly shift from administration toward enabling growth.

Advocating for statewide infrastructure, particularly more artificial surfaces, supporting clubs with increasing operational demands, strengthening long-term player pathways and leading statewide conversations about football’s future are all central.

What should be avoided are short-term decisions that undermine long-term development, leaving clubs to manage rapid growth without adequate support, duplicating efforts, or alienating clubs. Strong clubs, he believes, ultimately drive strong football outcomes statewide.

Three changes to lift standards

If he could lift standards in three years, Jon’s answers are straightforward but closely connected.

Facility upgrades across the state for year-round access, because consistent environments underpin consistent development.

Stronger alignment between youth and senior football, so players move through connected pathways rather than isolated teams and programs.

Improved operational and administrative support at clubs, because as expectations grow, clubs need systems that can carry the load rather than relying on overstretched volunteers.

For Jon, standards do not rise through words alone. They rise when the environment makes higher standards normal day to day.

His message to players and coaches

Jon’s message to players and coaches who want to improve is simple. Seek environments that demand more.

From his own journey, leaving England, transitioning out of playing and later stepping away from the corporate world, Jon says his biggest growth moments came when he chose environments that challenged him.

Improvement comes from training consistently in structured, competitive environments, being accountable for your own development, understanding that higher standards require sacrifice, particularly in semi-professional settings and adopting a growth mindset that recognises progress is often gradual.

The hinge point

Tasmanian football sits at a hinge point.

Ambition is rising. Expectations are rising. The standards players want to reach are rising. But systems, infrastructure, and support are still trying to catch up. It is not a talent problem. It is an environment problem. That is where he believes the real gap sits.

Those who lean into higher standards now will not just improve themselves. They will help shape what the game here becomes next.

And that is the real work.

Playing Up in Football: Development or Status?

It’s a Saturday morning.

Parents line the fence. Coffee cups. Folding chairs. A game that looks like every other junior game.

Then someone says it, loud enough for a few people to hear.

“She should be playing up.”

It’s said with pride. Sometimes with frustration. Often with pressure.

Playing up has become a badge. A signal. A marker that a child is ahead.

But in football development, things are rarely that simple.

Because the question isn’t just can a child play up.

The real question is:

Is it helping them grow, or just helping adults feel reassured?

What does “playing up” actually mean?

Playing up simply means a child trains or plays in an older age group.

A 10-year-old in Under-11s.

A 13-year-old in Under-14s.

It is an age decision, not a talent certificate.

Playing up is a tool, not a trophy.

A personal example

My son Max was always tall for his age. He was born in March.

At one junior tournament we were asked to show his birth certificate because officials assumed he must be older. He simply looked more physically mature than the other boys.

It felt amusing at the time, but it was also a reminder of something important.

In junior sport, we often mistake early physical development for advanced ability.

Some children grow earlier. They are taller, stronger, faster sooner. Others catch up later. That timing difference shapes how kids are selected, coached and perceived.

The Relative Age Effect

There is another layer to this that many parents don’t realise.

In youth sport, children are grouped by calendar year. That means in one team, there can be nearly twelve months difference between the oldest and youngest players.

At age 10 or 11, twelve months is huge.

The child born in January can be almost a full year older than the child born in December. They are often bigger, stronger and more coordinated simply because they have had more time to grow.

Research calls this the Relative Age Effect.

It shows that players born earlier in the selection year are over-represented in junior teams and representative programs. They look more “advanced” when, in reality, they are simply older within their age group.

This doesn’t mean they aren’t talented.

But it does mean that what looks like ability can sometimes just be timing.

And later, as puberty evens things out, those early physical advantages often disappear.

Early advantage is often just early growth.

Why age groups don’t tell the full story

Within one age group, some children are nearly a year older, some hit puberty early, some much later.

Those differences can look like talent when they are really just timing of growth.

When playing up can help

Playing up can be useful when it stretches a player without overwhelming them.

Older games usually mean faster decisions, less time on the ball, more tactical demands and greater physical pressure.

That can accelerate learning if the player is ready.

In strong development environments, playing up is usually used part-time, not permanently.

A player might train with older players sometimes, play some matches up and still play in their own age group where they can lead, express themselves and build confidence.

That balance is where development tends to thrive.

But harder does not automatically mean better

If the challenge gap is too big, ball touches drop. Creativity disappears. Confidence shrinks. Enjoyment fades.

A child surviving is not the same as a child developing.

Development happens when challenge is balanced with confidence.

The child’s experience

A child playing up doesn’t think, “This is a good development stimulus.”

They think,

“I hope I don’t mess up.”

“I hope I’m good enough.”

“I don’t want to let people down.”

When challenge turns into fear of failure, learning slows.

Research consistently shows that loss of confidence and enjoyment, not lack of ability, is one of the biggest reasons young athletes leave sport.

Ball touches matter more than status

A child who touches the ball often, makes decisions and learns from mistakes may develop faster than a child who rarely sees the ball while trying to survive in an older game.

Exposure is not the same as development.

Football age is not just physical age

Some players can make a mistake and move on. Not be the best player on the field. Take feedback calmly. Stay confident when challenged.

Others are still learning those skills.

Emotional readiness is often the real divider.

Is it for the child or for the parent?

Let’s be honest. Sometimes it’s one, sometimes it’s the other.

When it’s for the child, you see freedom in their play. They still demand the ball. They try things. They leave the field talking about moments in the game.

When it’s about status, the focus becomes the label. Comparisons start. The child becomes quieter, safer, more cautious. The personality in their football shrinks.

Kids care about involvement.

Adults care about advancement.

Those are not the same.

What coaches see over time

After years in youth football, patterns appear.

Early playing up kids are not always the ones still playing at 17. Late developers often surge when puberty evens things out. Confidence and love of the game predict longevity more than early physical dominance.

Football development is a marathon. Playing up can’t be the trophy at the first checkpoint.

The goal is not to raise the best 11-year-old.

The goal is to raise the best 18-year-old.

Fast forward six years

Puberty has levelled the field. The early physical gap has closed.

What’s left?

Decision making.

Confidence.

Resilience.

Love of the game.

Those are the things that last.

Why coaches sometimes say “not yet”

When a coach says no, it may be about protecting the player, physically, emotionally and socially and keeping development steady rather than rushed.

It is not always a lack of belief.

At MSS and SHFC, our starting point is always a player’s true age group. That gives us a stable base for confidence, involvement and leadership opportunities. From there, we watch closely. We assess how a player copes with challenge, how they respond to mistakes, how they handle physical pressure and how they behave emotionally in games. If a player consistently shows they are ready for more, we may introduce opportunities to train or play up. But it comes after observation, not assumption.

Playing up is something earned through readiness, not awarded as a status symbol. coaches sometimes say “not yet”

Every parent feels this

The quiet worry that your child might fall behind. The urge to see them recognised. Progressing. Challenged.

That instinct comes from love.

The key is recognising when pride and comparison start driving decisions more than development.

Final thought

One day your child won’t remember what age group they played in.

They will remember whether they felt confident. Whether they felt capable. Whether football still felt fun.

Playing up is a tool, not a trophy.

Because we are not trying to win childhood.

We are trying to grow footballers who stay in the game.

If the NPL Shrinks to Six Teams, How the Pyramid Actually Works - Part 2

I do not claim to be a competition design expert, but I have spent enough time inside football to see how structures affect players, clubs and volunteers. I hear football people talking and, often, complaining. This is an attempt to start a practical conversation about what might actually work better.

I have sat in workshops where football has paid professionals to spend entire days, at considerable cost, discussing competition structure.

On one of those occasions, the outcome was the idea that all games should be played at the same kick-off time.

That was not something clubs had been asking for.

Yet it was presented as what the game supposedly wanted.

The result was a season of smaller crowds, fewer shared matchday experiences and an inability for people within football to support other clubs once their own game finished.

It was a reminder of something important.

Structure decisions shape the lived experience of the game. When those decisions miss the mark, the consequences are not theoretical. They show up in empty sidelines and disconnected competitions.

That experience has stayed with me.

Because it highlights why conversations about league design cannot just be abstract exercises or consultant reports. They need to reflect the reality of how football actually functions here.

Bigger Does Not Automatically Mean Stronger

Before getting into structure, there is a deeper assumption that needs to be addressed.

In Tasmania we often equate a bigger top tier with a stronger competition. More teams at the top can be presented as growth. It sounds positive. It signals inclusion. It is easier to explain to government and stakeholders.

But bigger does not automatically mean better.

League strength is not measured by how many teams are included. It is measured by how competitive the matches are, how intense the environment is week to week, how well players are developed and how strong the overall standard becomes.

When the player pool is spread too thinly, expanding the top division can actually lower the average level. Gaps widen. Uneven games increase. Survival football replaces performance football. The league looks larger, but the competition inside it becomes flatter.

Growth in numbers and growth in standard are not the same thing.

Sometimes concentrating quality lifts the whole system faster than spreading it.

That is not shrinking the game. It is strengthening it.

So if we are serious about the idea raised in Part One - a six-team NPL - the mechanics have to be clear.

This is what that system would look like.

Step One - The NPL

The top tier becomes six teams playing four rounds for a 20-match season.

This concentrates quality, increases weekly intensity and provides more meaningful football.

The bottom-placed NPL club does not go down automatically. They enter a promotion and relegation playoff.

A 20-game league season combined with structured cup competitions remains a moderate player load compared to many football environments. It spreads intensity across competitions rather than compressing it into a short league window.

Opportunity is not defined by how many teams sit in the top division but by how many meaningful competitive minutes players actually get.

Step Two - The Second Tier

The second tier remains regionalised with a Northern Championship and Southern Championship.

This respects travel realities and volunteer capacity. The top tier is where the strongest clubs already travel. Regionalisation below protects sustainability where it matters most.

Each competition runs its season to determine a Champion.

NPL clubs may field teams in these leagues but those sides are development teams and are not eligible for promotion. If such a team finishes first, eligibility passes to the highest-placed independent club.

Step Three - North vs South Playoff

The Champion of the North and the Champion of the South play a home-and-away playoff.

The winner becomes the Challenger.

This connects the regions at the point where performance matters and avoids assumptions about relative strength.

If the Challenger is not competitive over two legs, the gap between levels is exposed. That is valuable information for the system.

Step Four - Promotion and Relegation Playoff

The Challenger plays a home-and-away playoff against the bottom-placed NPL club.

The winner earns the NPL place for the following season.

Some will ask why the bottom NPL club gets a second chance. This model recognises the gap between tiers and makes the final movement a sporting contest at the interface of levels. It ensures the promoted club can compete immediately and that the NPL standard is protected.

If the playoff becomes one-sided, that is still information. It shows whether the gap between tiers is closing or not.

Step Five - Promotion Is Earned Through Performance and Confirmed Through Readiness

Winning is necessary. It is not sufficient.

Clubs must meet agreed NPL standards in areas such as ground suitability, lighting, medical provision, governance, financial sustainability and squad readiness.

Standards are not about exclusion. They are about clarity of level.

If the Challenger does not meet standards, promotion does not occur that season. The sporting result of the playoff cannot be bypassed by promoting a club that did not win the pathway.

Step Six - Promotion Intent Must Be Declared in Advance

Championship clubs must declare before the season begins whether they are eligible and willing to compete for promotion.

Only clubs that have declared intent and meet baseline readiness criteria can enter the promotion pathway.

Clubs that do not declare can still compete in the Championship competition but are not eligible for the playoff. If such a club finishes in a qualifying position, eligibility passes to the next highest-placed eligible club.

This prevents a situation where a club plays through the pathway and then declines promotion, which would stall the pyramid.

Adding Football the Right Way

A six-team NPL does not mean less football.

It means a different balance between league and cup football.

A structured summer cup in the South.

A formal Hudson Cup in the North.

The Lakoseljac Cup statewide.

The League title.

That creates four meaningful trophies across the season.

Cup football adds variation, knockout pressure and different tactical demands.

Cup competitions also do something league formats cannot.

They create unpredictability.

They give lower-league or less fancied clubs the chance to make a run, create moments and capture attention. That variety is part of football’s character. It brings different winners into the story and keeps more clubs feeling connected to meaningful outcomes across the season.

True cup football is compelling for spectators, valuable for media coverage and memorable for players. It produces stories that a league table rarely does on its own.

Crowds have been good for summer cups. The Hudson Cup provided strong football. Clubs have entered both.

League plus cups is not less football. It is more meaningful football.

Cups only add value when scheduled properly and treated as formal competitions, not friendlies in disguise.

This Is Simpler Than It Sounds

The structure sounds detailed, but the logic is simple.

Win your level.

Prove you are ready.

Compete for the place.

Playoffs add only a small number of additional match weekends and are manageable within a calendar freed by a 20-game league season.

A Transitional Step

Right now, standards checks are necessary because the ecosystem is uneven.

But the aim is that over time Championship-level clubs operate at a similar baseline. As that happens, the standards check becomes less of a gate and more of a formality.

The focus shifts back to performance on the field.

This model is not about keeping clubs out.

It is about creating a system that encourages clubs to grow into the level.

How the Transition From Eight to Six Teams Works

If the current NPL has eight teams, the move to six must be handled in a way that is clear, fair and based on football, not administration.

The simplest and most defensible transition is performance-based.

In the transition season, the NPL remains at eight teams.

At the end of that season, the bottom two teams on the ladder are relegated.

There is no automatic promotion that year.

The league naturally reduces from eight to six based on results on the field.

The new structure, including the Championship playoff pathway, begins the following season.

This avoids political decisions, historical arguments or subjective assessments. Every club starts the season knowing exactly what is at stake. Ladder position decides.

It is not about removing clubs. It is about resetting the scale of the top tier to match current depth.

Championship clubs are given advance notice that the promotion pathway begins the following year, providing time to prepare for standards and readiness requirements.

This keeps the transition sporting, transparent and fair.

Commit to It

The final piece is cultural.

Whatever model is chosen, it cannot change every season.

Clubs need certainty.

They need time to adjust, plan and grow.

If a new structure is altered at the first sign of discomfort, the system never settles.

Year one will feel different. Year two will still be bedding in. That does not mean it is wrong. It means the game is adapting.

Competition structures only work when they are formal, stable and treated as important.

This model is not about tinkering.

It is about committing.

Set the structure. Make it clear. Let clubs work within it.

Standards rise over time, not overnight.

When I Said “Women Aren’t Loud Enough”

At yesterday’s club strategic planning meeting we were discussing a familiar issue.

Why don’t more women coach?

I made a comment that came out easily. Almost casually.

Women often aren’t loud or commanding enough to control a group of boisterous 11-year-olds. In junior football you have to dominate the space.

Heads nodded. It sounded practical. Experience-based. Sensible.

Then Mark Moncur, who is heavily involved in gymnastics and sits on our board, said something that stopped me.

Most of his coaches are women.

They manage large groups of energetic kids.

They cope very well.

And just like that, my confident explanation didn’t feel so solid.

Because if women can do it there, why not here?

So I’ve been sitting with what I said.

Was I describing reality?

Or was I describing football culture?

It’s uncomfortable to realise I may have repeated the same assumptions that have limited women in the game for years.

Was I wrong?

The honest answer is uncomfortable.

I wasn’t completely wrong about the environment. Junior football, especially boys in that 8 to 12 age, can be loud, chaotic, physical and full of boundary testing. You do need presence. You do need authority.

But I may have been wrong about who is capable of that.

And more importantly, I may have described the style of authority football is used to, not the only kind that works.

1. The environment women are stepping into

Coaching this age group is not just teaching skills.

It is behaviour management.

Noise management.

Parent management.

Open parks. Parents three metres away. Every instruction audible. Every decision visible.

And football is still culturally coded as male territory.

So for many women, stepping in is not just taking a role. It is stepping into a space where authority is more likely to be questioned.

A man raising his voice is often seen as strong.

A woman raising her voice can be judged very differently.

That double standard is tiring before the whistle even blows.

2. Authority is socially taught, not naturally owned

When we say junior coaching requires someone to be loud and commanding, we are really talking about comfort with visible authority.

Boys are more often encouraged to be loud, to take up space, to lead physically and verbally.

Girls are more often corrected for the same behaviour, told not to be bossy, pushed toward harmony.

So by adulthood, when someone stands in front of a group of energetic boys, they are not just coaching.

They are pushing against years of social conditioning about how much space they are “allowed” to take up.

That is not about ability. It is about confidence under social pressure.

3. Many women don’t see themselves in the role

In sports like gymnastics, netball or dance, most coaches women saw growing up were women. The authority figure looked like them.

In football, most coaches they saw were men.

So women don’t just think, Can I do this?

They think, Do I belong here?

Belonging is powerful. Without it, people hesitate.

4. Fear of judgement hits harder in football

A new male coach can be rough around the edges and it is seen as part of learning.

A new female coach often feels like she represents all female coaches.

Mistakes feel public. Visible. Attributed to gender, not experience.

Add dads on the sideline, boys testing boundaries and existing male coaches nearby and it can feel like a performance, not a learning space.

That emotional load adds up.

5. The pathway into coaching is different

Many male coaches come through a simple pathway.

I played, so I will coach.

Women’s playing pathways have historically been shorter, less competitive and less resourced.

So many women feel they did not play at a high enough level to coach, even though junior coaching is largely about communication, organisation, care and structure.

Skills many women already have, but do not recognise as coaching credentials.

6. It’s not that women can’t handle boys

It’s that the system doesn’t support them doing it

Women who do coach juniors successfully often have

A co-coach

A club that backs them publicly

Clear behaviour standards

Visible authority from leadership

When that backing is not obvious, they feel exposed.

And exposed people leave.

7. Why gymnastics looks different

Gymnastics is not quiet or passive. Kids run, fall and push limits.

But the authority style often looks different. Structured. Precise. Expectation-driven. Consistent rather than loud.

The coach doesn’t “dominate the space”. The structure does.

Football, on the other hand, has a louder behavioural environment, more public criticism culture and a higher tolerance for chaos.

So women are not avoiding coaching children.

They may be avoiding environments where authority is contested, support feels thin and mistakes feel amplified.

The shift in my thinking

Maybe the issue isn’t volume.

Maybe it is

Do we introduce female coaches with visible authority?

Do we shut down sideline interference?

Do we set behaviour standards that back them?

Do we pair them, support them, protect their space?

Or do we hand them cones, wish them luck and then judge whether they were “strong enough”?

That’s a system issue.

So was I wrong?

I was right that junior football is a demanding environment.

But I was wrong to imply the limitation sits with women.

The limitation may sit with how football defines authority and how little we have adapted that definition.

Maybe the question isn’t whether women are ready for football coaching.

Maybe it’s whether football is ready to make room for different kinds of authority.

That’s a humbling thing to admit.

But maybe that is exactly where change starts.

Why a Six-Team NPL Makes Competitive Sense - Part 1.

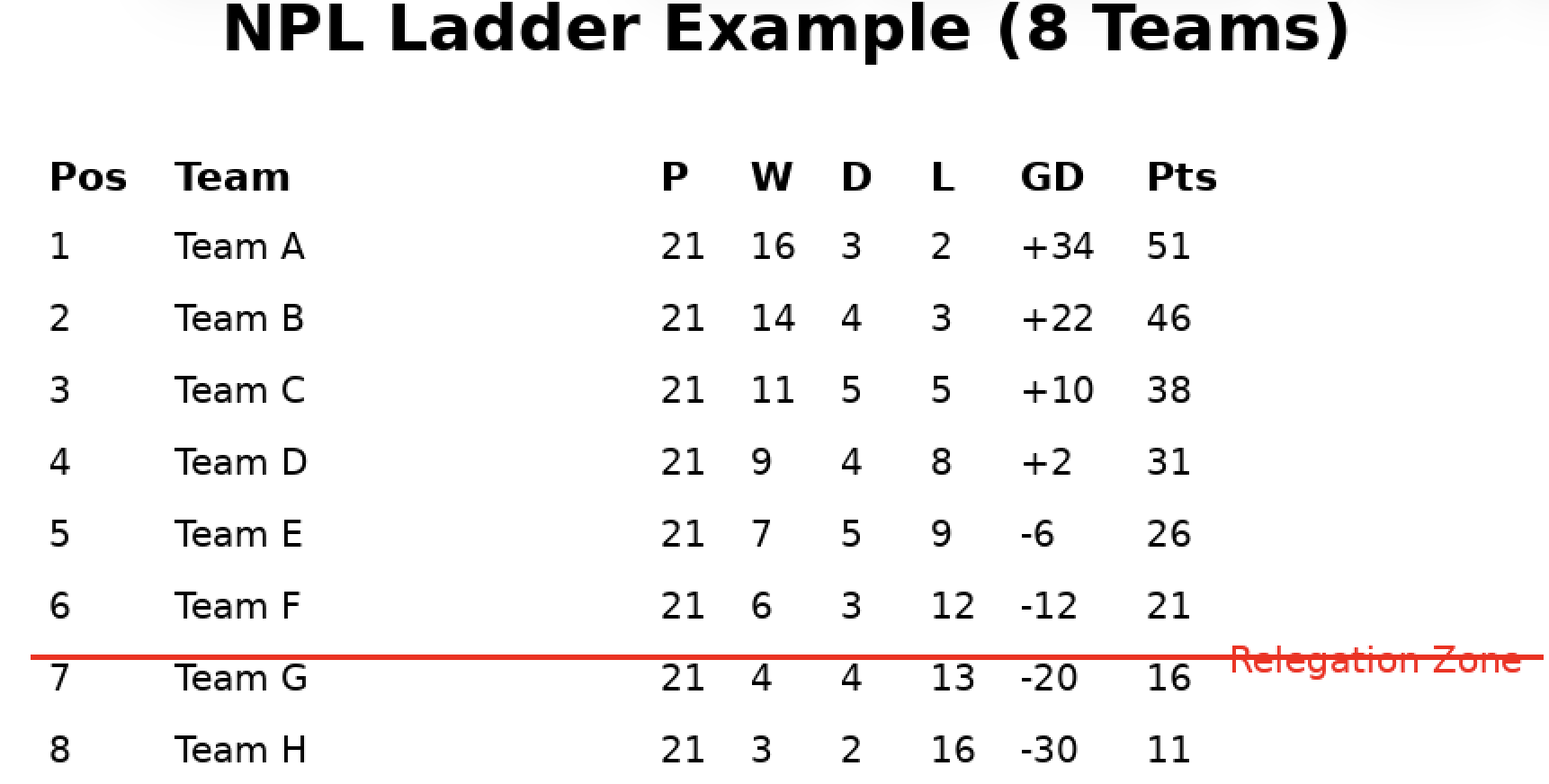

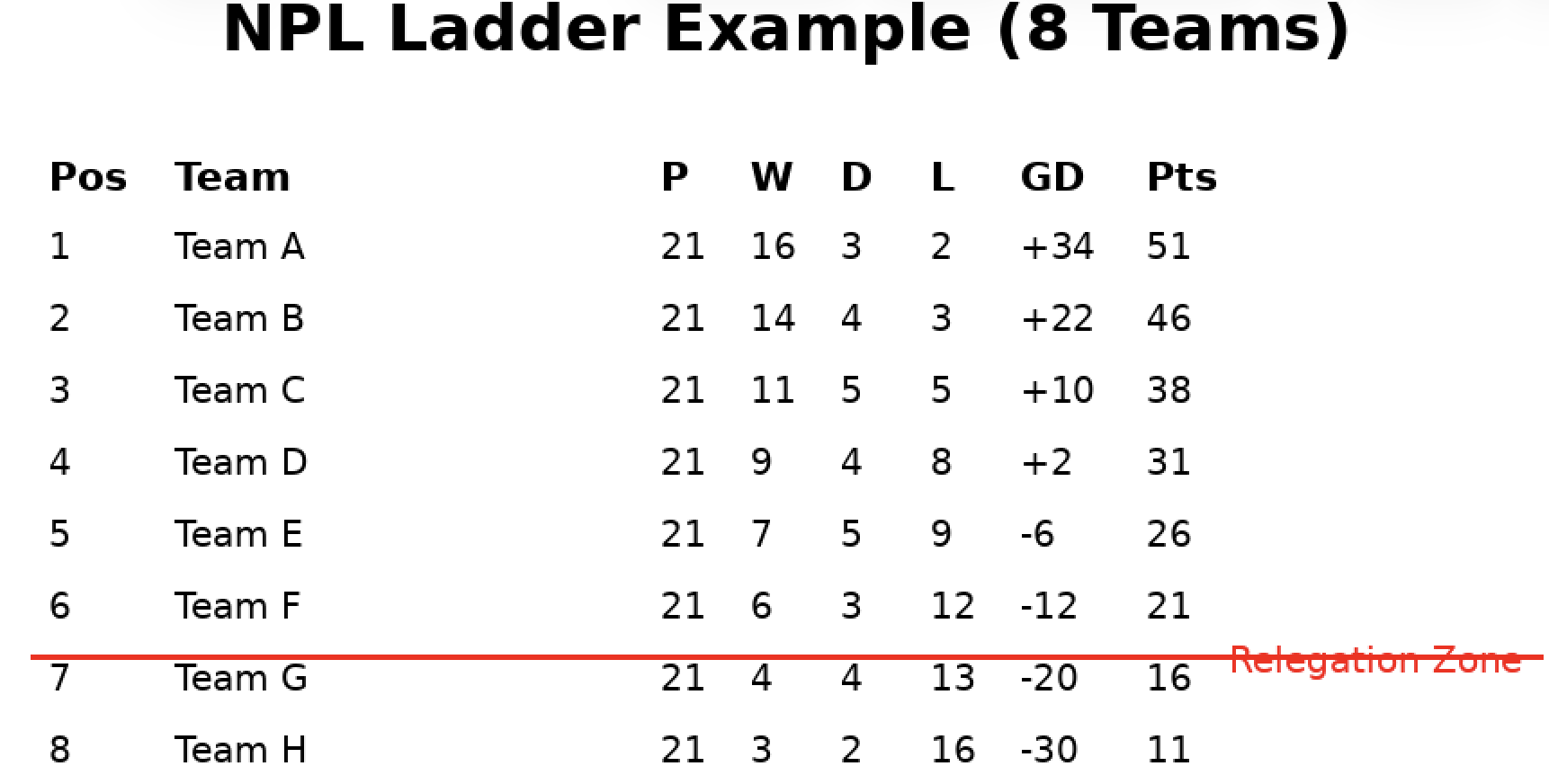

2025 Tasmanian NPL League Table

Yesterday our club held a Board strategic planning session.

Across a wide range of topics, one issue surfaced more than once.

Eighteen games.

Not enough football.

Not enough minutes.

Not enough exposure.

Not enough sustained pressure for players trying to develop at senior level.

It is easy to criticise structures from the outside. It is harder and more useful, to think through what the alternatives might actually look like.

That conversation made me stop and shift perspective.

Instead of pointing out what is not working, what are the practical options. What are the trade-offs. What are the uncomfortable decisions that come with designing a competition that genuinely lifts standards.

Because this is not a simple problem.

Tasmania has geography.

Volunteer-run clubs.

Travel realities.

A small player pool.

A desire to be competitive nationally.

Any structure has to live inside all of those constraints.

But constraints do not remove the central question.

If we accept that eighteen games is not enough meaningful football for the top level, what league design makes the most sense.

This is not about who belongs where.

It is about competitive design.

Reading the Ladder as a Diagnostic Tool

League tables tell stories beyond who finished first.

When recent NPL results are viewed as patterns rather than names, the competition does not look like one tight race. It looks like three distinct performance bands.

A top group separates strongly. High points totals. Large goal difference. High scoring. Few conceded. These teams are tested occasionally, not consistently.

A middle group competes tightly with each other. Balanced results. Moderate goal difference. This is where the most developmentally valuable football tends to occur.

A survival group concedes heavily and carries large negative goal difference. These teams are not simply losing. They are operating at a different depth level. In these environments teams often move into survival mode. Risk reduces. Young players are protected. Confidence erodes. Development slows.

This is not a criticism of any club.

It is a structural signal.

When a league clusters into performance bands, it suggests the distribution of talent across the number of teams may not align with the size of the player pool.

The Scale of the Gap Matters

When we look at the numbers more closely, the goal difference spread across the league was not small.

It was significant.

The teams at the top of the table were operating with very strong positive goal difference, scoring freely and conceding very little. At the other end, some teams carried heavy negative goal difference and high goals conceded totals.

That is not just variance.

That level of separation tells us the competition was not functioning as one consistent performance environment. It suggests a gap in depth, experience and squad capacity across the number of teams at the level.

When the difference between top and bottom becomes that large, several things happen.

Top teams are not stretched often enough.

Bottom teams operate in survival mode rather than development mode.

The middle of the table carries most of the genuinely competitive load.

That is not a criticism of individuals or clubs.

It is a signal that league structure and player distribution may not be aligned.

Why Blow-Outs Matter

Heavy scorelines are not moral failures.

They are indicators.

When the gap between strongest and weakest becomes too wide, top players are not stretched in certain fixtures. Coaches cannot replicate national-level intensity. Spectators disengage from predictable outcomes. The overall standard plateaus rather than rises.

Close games build atmosphere. Rivalries gain meaning. Late-season matches matter. Supporters stay engaged.

Competitive balance is not just about entertainment.

It is about whether the weekly environment resembles the level we say we are developing players for.

Two Structural Levers

There are only two ways to change this.

The number of rounds.

The number of teams.

Both influence player minutes, squad depth pressure, weekly intensity and national competitiveness.

Option One — Eight Teams, Four Rounds

Seven opponents multiplied by four equals twenty eight matches.

This increases exposure. Rotation becomes possible. Injuries do not derail development. The table reflects consistency.

This is the volume model.

But it only works if squad depth across eight clubs keeps matches competitive week after week. More games do not automatically mean more high-level games.

Option Two — Six Teams at the Top Level

Five opponents multiplied by four equals twenty matches.

Fewer total games, but higher intensity.

Stronger squads.

More top-v-top football.

Fewer survival line-ups.

More games where outcomes are genuinely in doubt.

This is the concentration model.

It assumes development comes through sustained pressure rather than pure volume.

Movement Matters

Structure alone does not lift standards.

Movement does.

Promotion and relegation introduce consequence.

Performance determines position.

Complacency has risk.

Ambition has a pathway.

A smaller top league only works if it is open.

If a Championship club wins but chooses not to go up, that is a choice about competitive level. The next eligible club progresses. If none meet standards, the NPL remains unchanged. The structure cannot bend around reluctance.

Top-tier football is a performance environment, not a participation badge.

Geography Is Real

Tasmania is not a compact metro region.

Travel matters. Costs matter. Volunteer capacity matters.

The Championship tiers are already regionalised North and South. That should remain. Geography shapes the second tier.

But geography cannot be the sole determinant of top-tier structure. That leads to fragmentation, not progression.

The challenge is to design a system that manages geography while still demanding competitive standards.

Will Players Tire of Repeated Opponents

Some will ask.

That depends on what the league is for.

Variety is a participation value.

Repeated high-level opposition is a performance value.

Repeated fixtures build tactical depth, adjustment, rivalry and psychological resilience. That mirrors higher-level football.

Retention Matters

When capable players spend seasons underfed for minutes, they drift away.

Not because they do not love football.

Because they want to play.

Structure quietly shapes retention.

A Considered View

This is not complaint. These ideas come from long involvement in the game and recent discussions with Ken, whose experience spans generations and levels.

This is not a club position.

It is a competitive one.

Where This Leads

If a call must be made based on competitive reality rather than comfort, the model most likely to lift weekly standards is clear.

A smaller, open top division.

Six teams. Four rounds. Promotion and relegation.

Not to exclude.

To concentrate quality, increase intensity, create consequence and mirror the environments players face beyond the state system.

Expansion can follow when depth supports it.

Standards rise when structure demands more.

Identifying the structural problem is only the first step.

The next questions are harder.

How promotion and relegation would operate across North and South.

What happens when clubs decline to move up.

And how standards can be protected while geography is respected.

Those mechanics matter just as much as league size, and I will look at them next.

Jan Stewart, Kingborough Lions Football Club

Jan Stewart photographed by Nikki Long

Football Faces Tasmania, recorded 2022

Why Jan matters

I used to see Jan most weekends at football.

She is one of those people who just makes you feel good. Always friendly. Always caring. The kind of person you naturally drift toward because her energy is calm, warm and genuine.

Football clubs run on people like that.

I do not think Jan is coaching at the moment, which honestly makes me a little sad. Because she is one of the kindest people I think I have known in football and that kindness is not softness, it is strength. The girls who come through coaches like Jan learn more than football, they learn belief.

Jan Stewart is one of those people who makes football feel safe.

Not safe in a soft way. Safe in the way that makes you try again. Safe enough to be new. Safe enough to be awkward. Safe enough to learn in public. Safe enough to be brave.

Football is damn lucky to have her and so are the girls coming through who do not yet know what they are capable of.

This is a Football Faces Tasmania story from 2022. Jan wrote it herself, straight from the heart. I am publishing it now so it has a permanent home.

Jan’s story, in her words

Some years ago now, I came into the game as a football mum.

My son was 7 at the time. My 10 year old daughter was watching his training session from the sidelines and said, “Mum, can I play?”

I laughed warmly.

“Girls do not play football,” I responded.

Two weeks later she was registered in a mixed team, and now at 24 she is still playing, when it stops raining in Northern NSW.

When our youngest daughters decided at 6 to play, I became a coach, and a learner player.

I was not ever very skilled in my football playing journey.

However, I did learn enough to grow my skill as a coach, and also a great love for the game.

Fifteen years later, and many, many hours on the football park coaching and playing, I finally feel like I am beginning to understand. Growing also is my confidence.

For me, this is what I want to be able to instill and grow in our youth girls.

With confidence comes strength, which empowers the players with the belief that they can achieve anything they set their mind to. It helps them find their way for their confidence and strength to shine.

It begins with them mastering the simplest of skills, such as passing.

Accurately.

Not every player knows their ability.

Not every player has a support base behind them.

Not every player knows what a football pathway is.

Not every player has good mental health.

To be someone in their lives that offers positivity and belief, and shows them what they can achieve through playing football, is so rewarding, and a great privilege.

Be brave.

Be confident.

Be strong.

This is what I wish for our youth players, and I believe that you can be powerful young female footballers.

These skills will carry you through life.

Jan Stewart

Football Faces Tasmania

Football Faces Tasmania was created to celebrate the people who shape Tasmanian football.

You know most of them. You see them at games, in the canteen, at the gate, organising the club, buying the equipment, coaching the team, managing the team, keeping the lights on, literally and figuratively.

Whatever their role, they volunteer for the benefit of many and their contribution should not be forgotten.

The questions are asked by Victoria Morton. Photos are by Nikki Long.

If you know someone whose football story should be remembered and celebrated, please tell me.

Why the Matildas Feel Safe - And Men’s Football Still Doesn’t

Photo Vogue Australia

Why Sam Kerr Is Celebrated and a Socceroo Would Still Be a Shock

We all saw the joy around Sam Kerr’s wedding.

Celebration. Pride. Love. Visibility.

She is openly gay. It was not framed as bravery. It was simply life.

Sam Kerr’s wedding showed what acceptance can look like in football. It also quietly showed us where the men’s game has not yet arrived.

Now ask yourself this.

If a current Socceroo, in his prime, came out tomorrow, would the reaction feel the same?

We know the answer.

That difference is not really about sexuality.

It is about gender, power, masculinity, and the culture men’s football still carries.

The history men’s football still carries

Ken often talks about earlier decades in football. The 60s and 70s. He says there were players “everyone knew” about. Nothing was said openly. Just whispers, sniggering, coded comments behind hands.

That silence was not acceptance. It was containment.

Then in 1990, Justin Fashanu came out in England. The first male professional footballer to do so publicly. The reaction was brutal. Media frenzy. Isolation. Stigma. His story ended in tragedy.

That moment mattered.

Men’s football absorbed a lesson, not about inclusion, but about risk. The message that travelled through the game was simple, this is dangerous.

Women’s players have faced their own battles for respect, funding and legitimacy. But the cultural fight around sexuality unfolded differently in their game. Women’s football did not carry that same public trauma point. That difference still echoes.

Cultures remember, even when they don’t speak about it.

Where I sit in this story

Andy Brennan has been part of our football life since he was four years old. My son’s best mate. In and out of our home. One of “our boys”.

He is also a very good footballer. He came through South Hobart, earned a move to South Melbourne and later played in the A-League with Newcastle Jets. He has lived inside elite men’s football environments.

When he told me he was gay and that he was going to come out publicly, my first instinct was not judgement. It was fear.

Fear of crowds. Fear of headlines. Fear of what football environments can be like and what they would do to him.

That protective, mother reaction says as much about men’s football culture as any analysis does.

Andy went on to be more resilient than I imagined. Happier. More confident. More himself. But my first response was shaped by the history this game carries.

Women’s football grew differently

Women playing football were already stepping outside traditional gender expectations. The sport developed fighting for recognition, not protecting a long-established identity.

LGBTQ+ visibility became part of the culture early. Not as a campaign, but because players existed and did not hide.

So now:

Matildas share partners on social media

Sponsorship campaigns include same-sex relationships

Fans celebrate it as normal

The Matildas have been allowed to be whole people in public. Male players are still expected to be only footballers.

That visibility does not destabilise the identity of women’s football. It fits the story the game tells about itself.

The commercial contradiction

Women’s football is marketed around authenticity, diversity, community and relatability.

Men’s football has long been marketed around power, toughness, tradition and the “alpha” image.

LGBTQ+ visibility sits comfortably in the brand story of the Matildas.

It disrupts the traditional brand story of men’s football as it has been packaged for decades.

So you see visibility in the women’s game.

And near invisibility in the men’s.

Not because gay male players do not exist. But because openness is still treated as commercial and cultural risk.

Why men’s football reacts differently

Homophobia in men’s football is rarely just about sexuality. It is about policing masculinity.

Being gay has wrongly been treated as being “less of a man.” That idea lingers in dressing rooms, terraces and commentary culture.

A gay female player does not threaten a straight man’s identity.

A gay male player challenges the narrow definition of masculinity that sport has carried.

That discomfort sits underneath a lot of reactions, even when no one says it aloud.

The role model burden in men’s football

In the men’s game, coming out rarely stays a private act.

A player does not just remain a winger, a defender, a teammate.

He becomes “the gay footballer,” a spokesperson, a symbol, a headline.

His identity becomes part of his public job, whether he wants it to or not.

That is exhausting.

Women’s football has reached a point where sexuality is increasingly just part of who someone is, not the defining narrative. In men’s football, the story still attaches itself to the person.

That added pressure, media attention and expectation to represent a whole community is another reason some players stay silent.

Silence in men’s football has often been less about shame and more about survival.

Crowd culture matters but not in the way people think

Go to a Matildas game and you will see just as many men as women. Dads. Brothers. Young boys. Older men. Hardcore football fans.

Men who support the Matildas. Men who take their daughters. Men who cheer openly for gay players without hesitation.

So the issue is not that men cannot accept gay athletes.

It is that men’s professional football has historically built a performance culture in its terraces where aggression, banter and intimidation are part of the ritual. That culture developed over decades in men’s leagues.

Women’s football crowds grew in a different way. Not softer, but less tied to proving masculinity through confrontation. That difference shapes what behaviour feels normal in the stands.

It is culture of environment, not gender of spectators.

Progress, but slow

Things are changing. Younger players grew up in a different world. Many dressing rooms today are more open than they were even ten years ago.

Clubs talk more about inclusion. Teammates often privately support each other more than people realise.

But football is tradition-heavy. Culture change often arrives with a generation, not a policy.

So progress exists. But for the individual player considering coming out, “things are better now” still does not feel like certainty. It still feels like stepping into the unknown.

That gap between progress on paper and safety in practice is where hesitation lives.

Why this matters

Somewhere there is a young girl watching the Matildas and seeing herself reflected.

Somewhere there is a young boy in football who still feels he must hide.

The difference is not talent.

It is culture.

And culture can change.

Before we hear personal stories, we need to understand the environment those stories sit inside.

James Sherman: Coming Home With New Eyes

James Sherman - Another terrific photo by Nikki Long

Season 2026, Glenorchy Knights FC

James Sherman is one of those coaches who makes you feel optimistic about football.

Not because he talks loudly, or sells himself well, but because he is thoughtful, grounded, and serious about the work. James loves football, and you can tell quickly that the game still excites him, not just for what happens on a Saturday, but for what can be built over years.

James coached Glenorchy Knights from 2019 to 2024, then stepped away to work in Singapore in a player development role. Now he returns for the 2026 season as NPL Head Coach and in a broader technical leadership position across the club.

As part of my own written record of Tasmanian football, it felt important to capture James’s thinking in his own time, because coaches like this shape far more than just one team.

What follows is James Sherman’s reflection on football, coaching, Singapore, and what Tasmania needs to do if it wants to genuinely improve.

A football beginning

James’s earliest football memory is simple.

Kicking the ball with his mum in the backyard at home.

He says most sports were interesting as a child, but football just clicked, and it was easily accessible. There was always a ball nearby, always a game to be found. Once the love of it landed, it never really left.

When playing ends and coaching begins

Like many players, James expected to play for as long as he could.

But football has a way of forcing decisions on you. In pre-season 2016, he began having serious Achilles issues. It became apparent things weren’t going to improve much, and that got him thinking about what happens after playing.

That same year, he completed his C Licence.

Things progressed from there.

The people who shape you

When James talks about influence, he does not begin with elite programs or famous coaches.

He starts with family.

His mum and brother shaped him more than anyone. He also speaks with deep appreciation about the Armstrong family, who took him in as a sixteen-year-old straight out of Tasmania.

He was fortunate to have what he describes as stellar teammates, men who might be considered old school today, but who valued standards, care, and looking after each other.

That experience carries into the way he leads.

There are things that just matter, he says, and people caring about the small things makes a difference.

Small things add up.

Flexibility is not weakness

James is open about early coaching mistakes.

In 2019, Glenorchy Knights went through the middle of the season with six losses in a row. He reflects that they were trying too hard to match teams that were stronger.