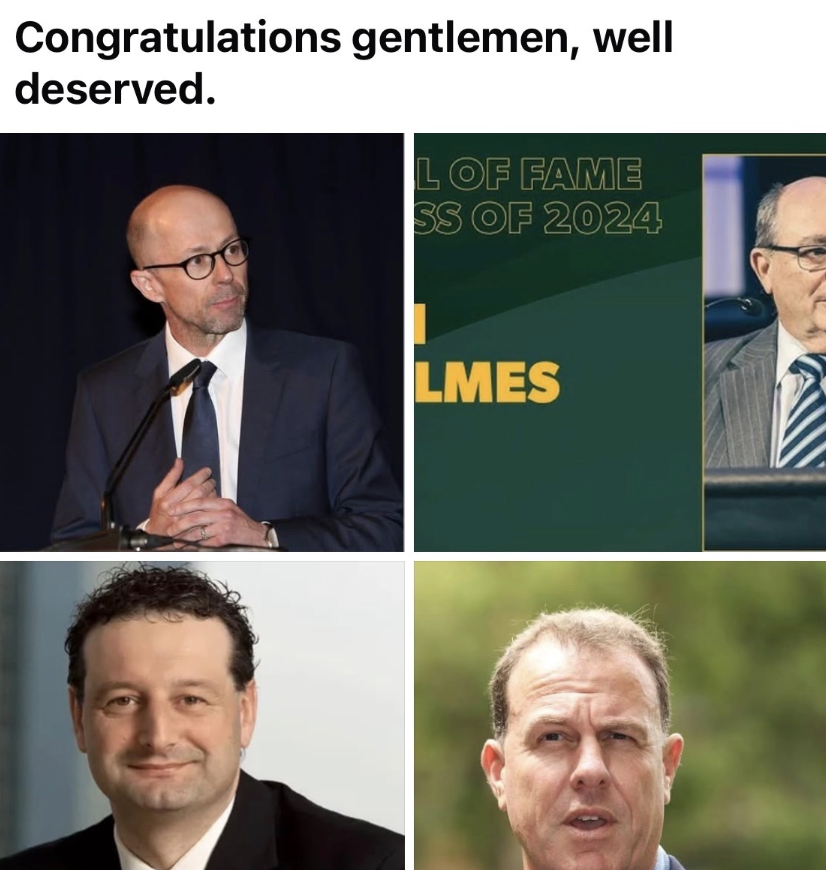

Who Football Chooses to Honour

Every so often football celebrates one of its leaders.

A medal.

An award.

A formal citation.

Words like service, leadership, contribution, legacy.

And each time, something interesting happens.

The people at the top nod.

The people at the bottom go quiet.

Not angry.

Not outraged.

Just… tired.

Two different footballs exist at the same time

There is the football of boardrooms, strategy documents, governance reform and executive titles.

That football speaks the language of impact, systems, growth, sustainability and national pathways.

It is structured.

It is reportable.

It is visible.

That is the football awards are built to see.

Then there is the other football.

The football that doesn’t appear in citations

This football looks like line marking at 7am, fixing nets with cable ties, chasing unpaid fees and calming upset parents.

It looks like running canteens, cleaning changerooms, writing grants at midnight and finding a fill-in keeper when someone doesn’t turn up.

It looks like turning up week after week, season after season.

Knowing families, players and volunteers across generations.

Making sure every child is accounted for at training and matches.

Holding teams together when numbers drop and seasons get hard.

This football does not have job titles.

It has people.

Recognition flows one way

In our game, recognition usually travels upward.

Formal honours go to executives, administrators and system-level leaders.

Meanwhile responsibility flows the other way.

Downward.

To volunteers.

To clubs.

To community football.

They implement.

They comply.

They absorb costs.

They absorb pressure.

They absorb fallout.

And they do it for free.

Community football also runs on a long-standing expectation that people will give endlessly and ask for little, because it is “for the love of the game”.

That culture of gratitude is powerful. It keeps the game alive. But it also helps explain why visibility for this kind of service has historically lagged behind.

What took so long

It is also worth pausing on something else.

Football built competitions, pathways, executive structures and governance systems long before it built formal ways of honouring the people who sustained the game locally.

Systems to regulate clubs came before systems to recognise community service.

The fact that local halls of recognition are such a recent development says something.

Not about individuals.

About priorities.

Community contribution existed long before formal recognition structures did.

Football has always relied on it. It just did not always record it.

Visibility versus reality

The football that is visible at national level is structured and measurable.

The football that keeps the game alive is messy, human and constant.

It does not have KPIs.

It does not come with tenure.

It does not produce glossy reports.

It simply turns up, every week, every season, for decades.

Moments of high-level recognition often highlight the gap between the football that is visible and the football that is lived.

Who is missing

There is another pattern that is harder to ignore.

Women have driven enormous growth in football in recent years. Junior participation, girls’ pathways, safeguarding, club administration, community engagement, retention. Much of that work has been led or carried by women.

Yet formal recognition structures still struggle to reflect that reality.

That is not about whether any individual deserves an honour. It is about the pipeline that leads to recognition.

Historically, men have occupied more of the titled, visible leadership roles that honours systems recognise.

Women have often done the organising, sustaining and fixing.

One type of contribution has tended to be recorded as leadership.

The other has often been absorbed as support.

The absence tells its own story.

What football chooses to honour tells us something

Awards are not just about individuals.

They are signals.

They show which forms of service the system sees most clearly.

Which roles carry prestige.

Which types of impact are considered leadership.

Volunteers notice that.

They see the structure being celebrated.

They live the substance.

And sometimes that creates a quiet sense of distance, a feeling that the version of football being recognised is not quite the one they experience every week.

Both things can be true

Professional administrators matter.

So do volunteers.

National leadership matters.

So does the person who unlocks the shed every Saturday morning.

Recognition at one level does not cancel out contribution at another. But when visibility consistently sits in one place, it is worth reflecting on what that says about how the game understands value.

The quiet truth

Grassroots football does not run on honours.

It runs on obligation, love of the game and people who simply keep turning up.

No medal required.

And perhaps the next step for football is not to question who is recognised, but to keep widening how we define service, leadership and legacy, so that the full shape of the game can be seen.