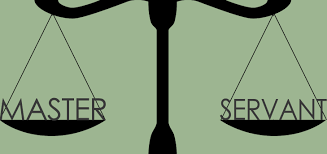

Master and Servant - paying to be Governed

There is an uncomfortable dynamic at the heart of football governance that we rarely name.

Clubs fund the system.

Governing bodies are paid to run it.

Volunteers deliver it.

Somewhere in that arrangement, roles blur.

We pay to be governed yet often feel unheard. Governing bodies are tasked with serving the game yet must exercise authority. Volunteers carry the workload, yet resist being directed. Everyone feels the tension, even if we lack the language for it.

With some distance from formal roles, and more time to reflect, the patterns have become harder to ignore.

That tension sits uneasily between two ideas.

Master and servant.

Paying to be governed

Football clubs do not sit outside the governance system. They fund it.

Affiliation fees.

Levies.

Licensing costs.

Compliance charges.

Money flows upwards. Clubs pay to participate. They pay to be regulated. They pay to be governed.

It is not unreasonable that payment creates expectation. When clubs contribute financially, they expect to be listened to. They expect decisions to reflect lived reality. They expect the burden to be understood.

This is not entitlement. It is a natural consequence of funding a system from below.

Authority and responsibility

Governing bodies, in turn, carry responsibility for the whole game. They are required to make decisions that apply broadly and consistently. They must balance competing interests. They must say no. They must absorb dissatisfaction.

They cannot please everyone. They are paid because someone has to hold that line.

This is where the relationship becomes strained.

Clubs experience decisions as distant or imposed. Governing bodies experience feedback as constant pressure. Both feel misunderstood.

Neither position is entirely comfortable.

The volunteer shield

Over the years I have heard the phrase many times.

You can’t tell me what to do, I’m a volunteer.

It is often said with conviction, sometimes with frustration, and sometimes with pride. Volunteering is a badge of honour. It signals contribution, generosity and commitment. It carries moral weight.

In many ways, it deserves respect.

But football no longer operates in a space where that statement is entirely true.

Volunteers are subject to rules, standards and decisions made elsewhere. Safeguarding frameworks, licensing criteria, governance requirements and compliance obligations apply regardless of whether a role is paid or unpaid.

Governing bodies can, in fact, tell volunteers what to do.

That reality sits uncomfortably alongside the deeply held belief that volunteering should come with autonomy.

Where it breaks down

This contradiction sits at the centre of much of the frustration in football.

Clubs pay to be governed, and expect to be heard.

Governing bodies are paid to govern, and must exercise authority.

Volunteers deliver the system, and resist being directed.

Each position makes sense on its own. Together, they create friction.

Money changes expectations. Volunteering creates resistance to control. Authority exists without ownership. Responsibility exists without power.

No one feels fully served.

Voice and being heard

Much of the tension plays out around voice.

Who gets to speak.

How they speak.

And whether speaking results in change.

AGMs, emails, committees and formal consultation processes provide opportunities to speak. They do not always provide the experience of being heard.

Being allowed to contribute feedback is not the same as shaping outcomes. When decisions are made elsewhere, or when consultation feels procedural, frustration grows.

The role of the CEO

In practice, the CEO often becomes the central figure in this dynamic.

Over many years as a club President, I dealt with a number of CEOs. Some listened well. Some did not. The difference mattered.

When the relationship worked, the role was manageable, even when issues were complex or decisions were difficult. When it didn’t, the role became significantly harder.

That is not because a President expects agreement. Disagreement is part of governance. It is because, when issues arise, the CEO is often the first and sometimes the only point of contact for clubs trying to navigate the system.

When you are a club President and problems emerge, who do you speak to within the governing body? Who helps interpret decisions, provide context, or offer advice when written rules do not neatly fit lived reality?

Boards are removed by design. Committees meet periodically. Formal processes are slow. The CEO becomes the conduit, the interpreter, the sounding board and sometimes the shock absorber.

In a small football state, this role carries particular weight. There are fewer layers, fewer alternative pathways and fewer places to go. When that central relationship functions well, tension can be absorbed. When it does not, frustration escalates quickly.

This is not about personality or popularity. Most people in these roles are trying to do the right thing. But in a small system, leadership style amplifies existing tension rather than containing it.

The cost of ambiguity

Football sits in an awkward space.

It is funded from below.

Delivered by volunteers.

Governed by paid professionals.

Roles overlap. Expectations collide.

Clubs feel like customers and subjects at the same time. Governing bodies feel like servants and masters at the same time.

This ambiguity is not accidental. It is structural. And it carries a cost.

Frustration.

Burnout.

Disengagement.

Mistrust.

It also leaves people carrying tension that is not theirs to resolve, long after meetings end and emails are sent.

For me, that sense of helplessness and the accumulation of frustration over many years, eventually became a factor in stepping away from formal leadership roles. Not because I stopped caring, but because carrying unresolved tension for too long comes at a personal cost.

None of these are caused by bad intent. They arise when systems outgrow the assumptions they were built on.

An unresolved tension

This is not an argument for less governance, or for unpaid administrators to carry more authority. It is not a call for blame.

It is an attempt to name a paradox.

Football asks clubs to fund the system, governing bodies to control it and volunteers to deliver it. Each role carries expectation. Each carries pressure.

Perhaps the real difficulty is not deciding who is master and who is servant, but acknowledging that the system asks all three to live with that ambiguity, every day.