If the NPL Shrinks to Six Teams, How the Pyramid Actually Works - Part 2

I do not claim to be a competition design expert, but I have spent enough time inside football to see how structures affect players, clubs and volunteers. I hear football people talking and, often, complaining. This is an attempt to start a practical conversation about what might actually work better.

I have sat in workshops where football has paid professionals to spend entire days, at considerable cost, discussing competition structure.

On one of those occasions, the outcome was the idea that all games should be played at the same kick-off time.

That was not something clubs had been asking for.

Yet it was presented as what the game supposedly wanted.

The result was a season of smaller crowds, fewer shared matchday experiences and an inability for people within football to support other clubs once their own game finished.

It was a reminder of something important.

Structure decisions shape the lived experience of the game. When those decisions miss the mark, the consequences are not theoretical. They show up in empty sidelines and disconnected competitions.

That experience has stayed with me.

Because it highlights why conversations about league design cannot just be abstract exercises or consultant reports. They need to reflect the reality of how football actually functions here.

Bigger Does Not Automatically Mean Stronger

Before getting into structure, there is a deeper assumption that needs to be addressed.

In Tasmania we often equate a bigger top tier with a stronger competition. More teams at the top can be presented as growth. It sounds positive. It signals inclusion. It is easier to explain to government and stakeholders.

But bigger does not automatically mean better.

League strength is not measured by how many teams are included. It is measured by how competitive the matches are, how intense the environment is week to week, how well players are developed and how strong the overall standard becomes.

When the player pool is spread too thinly, expanding the top division can actually lower the average level. Gaps widen. Uneven games increase. Survival football replaces performance football. The league looks larger, but the competition inside it becomes flatter.

Growth in numbers and growth in standard are not the same thing.

Sometimes concentrating quality lifts the whole system faster than spreading it.

That is not shrinking the game. It is strengthening it.

So if we are serious about the idea raised in Part One - a six-team NPL - the mechanics have to be clear.

This is what that system would look like.

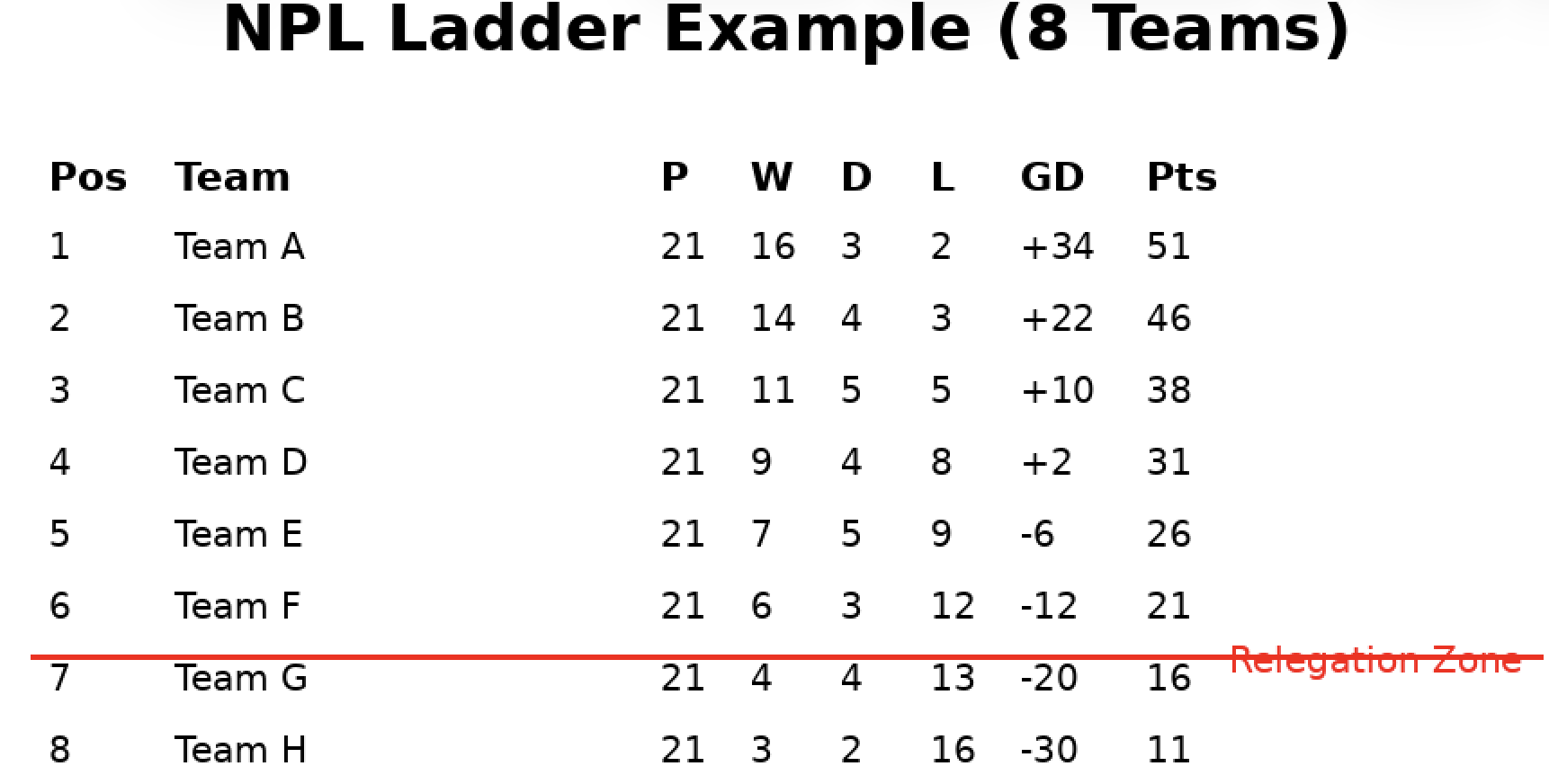

Step One - The NPL

The top tier becomes six teams playing four rounds for a 20-match season.

This concentrates quality, increases weekly intensity and provides more meaningful football.

The bottom-placed NPL club does not go down automatically. They enter a promotion and relegation playoff.

A 20-game league season combined with structured cup competitions remains a moderate player load compared to many football environments. It spreads intensity across competitions rather than compressing it into a short league window.

Opportunity is not defined by how many teams sit in the top division but by how many meaningful competitive minutes players actually get.

Step Two - The Second Tier

The second tier remains regionalised with a Northern Championship and Southern Championship.

This respects travel realities and volunteer capacity. The top tier is where the strongest clubs already travel. Regionalisation below protects sustainability where it matters most.

Each competition runs its season to determine a Champion.

NPL clubs may field teams in these leagues but those sides are development teams and are not eligible for promotion. If such a team finishes first, eligibility passes to the highest-placed independent club.

Step Three - North vs South Playoff

The Champion of the North and the Champion of the South play a home-and-away playoff.

The winner becomes the Challenger.

This connects the regions at the point where performance matters and avoids assumptions about relative strength.

If the Challenger is not competitive over two legs, the gap between levels is exposed. That is valuable information for the system.

Step Four - Promotion and Relegation Playoff

The Challenger plays a home-and-away playoff against the bottom-placed NPL club.

The winner earns the NPL place for the following season.

Some will ask why the bottom NPL club gets a second chance. This model recognises the gap between tiers and makes the final movement a sporting contest at the interface of levels. It ensures the promoted club can compete immediately and that the NPL standard is protected.

If the playoff becomes one-sided, that is still information. It shows whether the gap between tiers is closing or not.

Step Five - Promotion Is Earned Through Performance and Confirmed Through Readiness

Winning is necessary. It is not sufficient.

Clubs must meet agreed NPL standards in areas such as ground suitability, lighting, medical provision, governance, financial sustainability and squad readiness.

Standards are not about exclusion. They are about clarity of level.

If the Challenger does not meet standards, promotion does not occur that season. The sporting result of the playoff cannot be bypassed by promoting a club that did not win the pathway.

Step Six - Promotion Intent Must Be Declared in Advance

Championship clubs must declare before the season begins whether they are eligible and willing to compete for promotion.

Only clubs that have declared intent and meet baseline readiness criteria can enter the promotion pathway.

Clubs that do not declare can still compete in the Championship competition but are not eligible for the playoff. If such a club finishes in a qualifying position, eligibility passes to the next highest-placed eligible club.

This prevents a situation where a club plays through the pathway and then declines promotion, which would stall the pyramid.

Adding Football the Right Way

A six-team NPL does not mean less football.

It means a different balance between league and cup football.

A structured summer cup in the South.

A formal Hudson Cup in the North.

The Lakoseljac Cup statewide.

The League title.

That creates four meaningful trophies across the season.

Cup football adds variation, knockout pressure and different tactical demands.

Cup competitions also do something league formats cannot.

They create unpredictability.

They give lower-league or less fancied clubs the chance to make a run, create moments and capture attention. That variety is part of football’s character. It brings different winners into the story and keeps more clubs feeling connected to meaningful outcomes across the season.

True cup football is compelling for spectators, valuable for media coverage and memorable for players. It produces stories that a league table rarely does on its own.

Crowds have been good for summer cups. The Hudson Cup provided strong football. Clubs have entered both.

League plus cups is not less football. It is more meaningful football.

Cups only add value when scheduled properly and treated as formal competitions, not friendlies in disguise.

This Is Simpler Than It Sounds

The structure sounds detailed, but the logic is simple.

Win your level.

Prove you are ready.

Compete for the place.

Playoffs add only a small number of additional match weekends and are manageable within a calendar freed by a 20-game league season.

A Transitional Step

Right now, standards checks are necessary because the ecosystem is uneven.

But the aim is that over time Championship-level clubs operate at a similar baseline. As that happens, the standards check becomes less of a gate and more of a formality.

The focus shifts back to performance on the field.

This model is not about keeping clubs out.

It is about creating a system that encourages clubs to grow into the level.

How the Transition From Eight to Six Teams Works

If the current NPL has eight teams, the move to six must be handled in a way that is clear, fair and based on football, not administration.

The simplest and most defensible transition is performance-based.

In the transition season, the NPL remains at eight teams.

At the end of that season, the bottom two teams on the ladder are relegated.

There is no automatic promotion that year.

The league naturally reduces from eight to six based on results on the field.

The new structure, including the Championship playoff pathway, begins the following season.

This avoids political decisions, historical arguments or subjective assessments. Every club starts the season knowing exactly what is at stake. Ladder position decides.

It is not about removing clubs. It is about resetting the scale of the top tier to match current depth.

Championship clubs are given advance notice that the promotion pathway begins the following year, providing time to prepare for standards and readiness requirements.

This keeps the transition sporting, transparent and fair.

Commit to It

The final piece is cultural.

Whatever model is chosen, it cannot change every season.

Clubs need certainty.

They need time to adjust, plan and grow.

If a new structure is altered at the first sign of discomfort, the system never settles.

Year one will feel different. Year two will still be bedding in. That does not mean it is wrong. It means the game is adapting.

Competition structures only work when they are formal, stable and treated as important.

This model is not about tinkering.

It is about committing.

Set the structure. Make it clear. Let clubs work within it.

Standards rise over time, not overnight.