Playing Up in Football: Development or Status?

It’s a Saturday morning.

Parents line the fence. Coffee cups. Folding chairs. A game that looks like every other junior game.

Then someone says it, loud enough for a few people to hear.

“She should be playing up.”

It’s said with pride. Sometimes with frustration. Often with pressure.

Playing up has become a badge. A signal. A marker that a child is ahead.

But in football development, things are rarely that simple.

Because the question isn’t just can a child play up.

The real question is:

Is it helping them grow, or just helping adults feel reassured?

What does “playing up” actually mean?

Playing up simply means a child trains or plays in an older age group.

A 10-year-old in Under-11s.

A 13-year-old in Under-14s.

It is an age decision, not a talent certificate.

Playing up is a tool, not a trophy.

A personal example

My son Max was always tall for his age. He was born in March.

At one junior tournament we were asked to show his birth certificate because officials assumed he must be older. He simply looked more physically mature than the other boys.

It felt amusing at the time, but it was also a reminder of something important.

In junior sport, we often mistake early physical development for advanced ability.

Some children grow earlier. They are taller, stronger, faster sooner. Others catch up later. That timing difference shapes how kids are selected, coached and perceived.

The Relative Age Effect

There is another layer to this that many parents don’t realise.

In youth sport, children are grouped by calendar year. That means in one team, there can be nearly twelve months difference between the oldest and youngest players.

At age 10 or 11, twelve months is huge.

The child born in January can be almost a full year older than the child born in December. They are often bigger, stronger and more coordinated simply because they have had more time to grow.

Research calls this the Relative Age Effect.

It shows that players born earlier in the selection year are over-represented in junior teams and representative programs. They look more “advanced” when, in reality, they are simply older within their age group.

This doesn’t mean they aren’t talented.

But it does mean that what looks like ability can sometimes just be timing.

And later, as puberty evens things out, those early physical advantages often disappear.

Early advantage is often just early growth.

Why age groups don’t tell the full story

Within one age group, some children are nearly a year older, some hit puberty early, some much later.

Those differences can look like talent when they are really just timing of growth.

When playing up can help

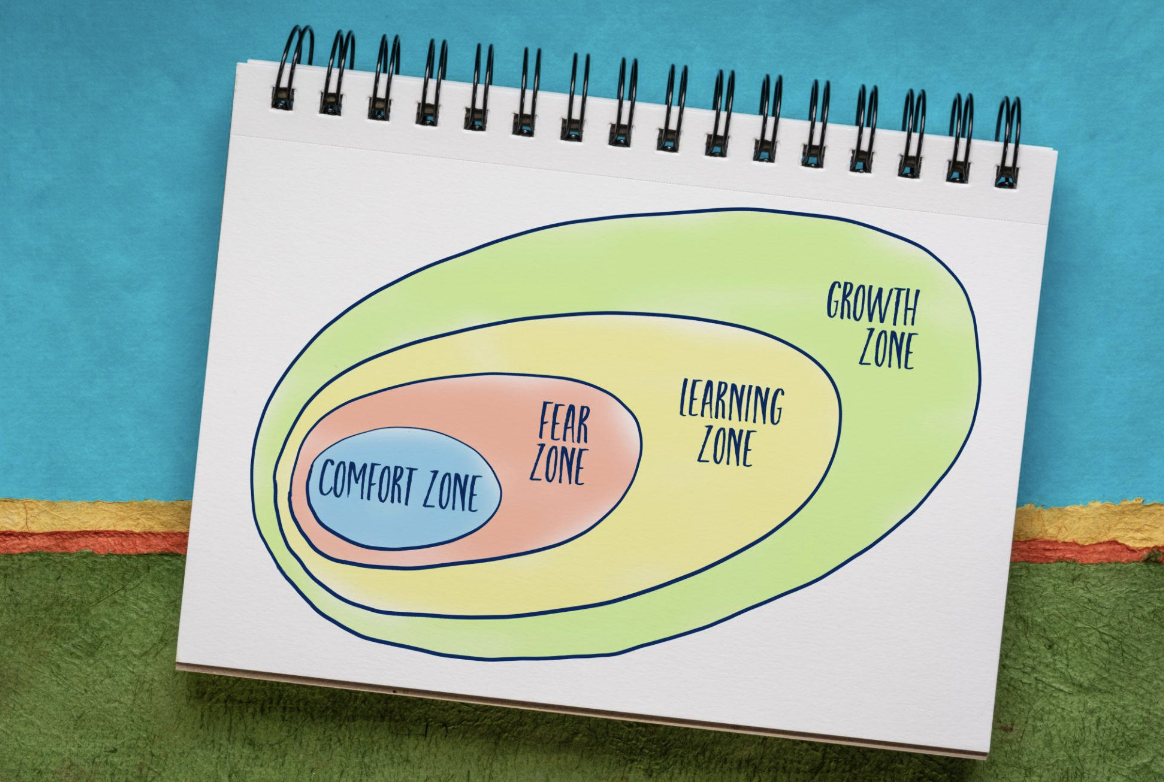

Playing up can be useful when it stretches a player without overwhelming them.

Older games usually mean faster decisions, less time on the ball, more tactical demands and greater physical pressure.

That can accelerate learning if the player is ready.

In strong development environments, playing up is usually used part-time, not permanently.

A player might train with older players sometimes, play some matches up and still play in their own age group where they can lead, express themselves and build confidence.

That balance is where development tends to thrive.

But harder does not automatically mean better

If the challenge gap is too big, ball touches drop. Creativity disappears. Confidence shrinks. Enjoyment fades.

A child surviving is not the same as a child developing.

Development happens when challenge is balanced with confidence.

The child’s experience

A child playing up doesn’t think, “This is a good development stimulus.”

They think,

“I hope I don’t mess up.”

“I hope I’m good enough.”

“I don’t want to let people down.”

When challenge turns into fear of failure, learning slows.

Research consistently shows that loss of confidence and enjoyment, not lack of ability, is one of the biggest reasons young athletes leave sport.

Ball touches matter more than status

A child who touches the ball often, makes decisions and learns from mistakes may develop faster than a child who rarely sees the ball while trying to survive in an older game.

Exposure is not the same as development.

Football age is not just physical age

Some players can make a mistake and move on. Not be the best player on the field. Take feedback calmly. Stay confident when challenged.

Others are still learning those skills.

Emotional readiness is often the real divider.

Is it for the child or for the parent?

Let’s be honest. Sometimes it’s one, sometimes it’s the other.

When it’s for the child, you see freedom in their play. They still demand the ball. They try things. They leave the field talking about moments in the game.

When it’s about status, the focus becomes the label. Comparisons start. The child becomes quieter, safer, more cautious. The personality in their football shrinks.

Kids care about involvement.

Adults care about advancement.

Those are not the same.

What coaches see over time

After years in youth football, patterns appear.

Early playing up kids are not always the ones still playing at 17. Late developers often surge when puberty evens things out. Confidence and love of the game predict longevity more than early physical dominance.

Football development is a marathon. Playing up can’t be the trophy at the first checkpoint.

The goal is not to raise the best 11-year-old.

The goal is to raise the best 18-year-old.

Fast forward six years

Puberty has levelled the field. The early physical gap has closed.

What’s left?

Decision making.

Confidence.

Resilience.

Love of the game.

Those are the things that last.

Why coaches sometimes say “not yet”

When a coach says no, it may be about protecting the player, physically, emotionally and socially and keeping development steady rather than rushed.

It is not always a lack of belief.

At MSS and SHFC, our starting point is always a player’s true age group. That gives us a stable base for confidence, involvement and leadership opportunities. From there, we watch closely. We assess how a player copes with challenge, how they respond to mistakes, how they handle physical pressure and how they behave emotionally in games. If a player consistently shows they are ready for more, we may introduce opportunities to train or play up. But it comes after observation, not assumption.

Playing up is something earned through readiness, not awarded as a status symbol. coaches sometimes say “not yet”

Every parent feels this

The quiet worry that your child might fall behind. The urge to see them recognised. Progressing. Challenged.

That instinct comes from love.

The key is recognising when pride and comparison start driving decisions more than development.

Final thought

One day your child won’t remember what age group they played in.

They will remember whether they felt confident. Whether they felt capable. Whether football still felt fun.

Playing up is a tool, not a trophy.

Because we are not trying to win childhood.

We are trying to grow footballers who stay in the game.