Governance + Politics

When the Australia Cup first arrived

August 2014

I was at this match.

It was the inaugural year of what was then the FFA Cup, now known as the Australia Cup. At the time, we were still working out what it meant. A national knockout competition. A genuine round of 32. A brief sense that Tasmania was no longer quite so far from the centre.

As Joe Gorman wrote in his piece for The Guardian at the time, “I’m here for the football… it’s at these local games where you find the most wonderful of football anoraks.”

That line has stayed with me, because it describes the people who carried nights like this long before anyone else was paying attention.

We were there because we had won the Lakoseljac Cup. That alone felt significant. It placed us into the round of 32 of a brand-new national competition, one that continues today and is now embedded in the Australian football calendar.

I remember being terribly nervous, mostly about the game itself. The occasion, the stage, the sense that this night mattered more than most. Mark being in goal added another layer to it, of course, but it wasn’t the source of the nerves. It was everything wrapped around the match that made it feel heavy.

Our regular goalkeeper, Kane Pierce, had been sent off the week before for bad language. We fought like mad to see if we could get him cleared. We argued the case. We appealed. But to no avail. Rules were rules, and Kane was out.

He was devastated. But we had no choice. The reserve goalkeeper stepped in and did a wonderful job, as people so often have to do in Tasmanian football.

One of the most memorable parts of that first Australia Cup experience had very little to do with what happened on the pitch.

The administrative and organisational workload was on another level. As a volunteer-run amateur club, we were suddenly required to operate at something approaching a professional standard. The volume of paperwork was daunting. Compliance, documentation, deadlines, processes we had never encountered before at that level.

Frances, our club secretary, carried the bulk of that work. She spent hours and hours making sure every box was ticked and every i dotted.

As Frances said to me at the time, “The workload was enormous and completely new for us, but we weren’t doing it in isolation. Mal was terrific to deal with, and John was very supportive. That made a big difference when you’re trying to meet standards you’ve never been held to before.”

In hindsight, it was formative. We built a strong working relationship with Mal Impiombato, who was our direct FFA contact throughout the process, and were well supported by the FFT CEO at the time, John Boulos. That first experience quietly set us up for our next two Australia Cup appearances and later for the yet-to-be-commenced Australian Championship, which brought similar levels of compliance and administrative load.

Those hours don’t make the highlights reel, but they are part of the story.

We couldn’t play at home either. We don’t have lights at our ground. We didn’t then, and we still don’t. The Australia Cup is played mid-week to fit within the national football calendar, so the match had to be moved. We played at KGV Park, a ground we knew well from league football, but one that felt different under lights, with that added sense of occasion.

Mark Moncur went in goal that night. He is now a board member and life member of the club, but on that evening he was simply someone stepping up when needed. He wore Kane’s white goalkeeper kit, which was very much not what he would have chosen himself. That detail has stayed with me. You wear what is available. You do what needs to be done.

There was also a familiar dread. The curse of penalties seemed to hang over us in the Australia Cup, even if it hadn’t yet fully announced itself that night. It would surface again in later years, most memorably against Sydney United 58. Once penalties enter your club’s story, they never really leave it. God, I hate penalties.

What strikes me now is this. What Kane was sent off for in 2014 would not even be a bookable offence in 2026. The rules of the game have changed. The interpretations have changed. The moment, though, remains fixed in time.

Later in his article, Gorman wrote that “cold weather, hot food and passionate support make for a memorable evening.”

That line captures it perfectly. Even in defeat, those nights mattered. They still do.

You can read the full article here:

https://www.theguardian.com/football/blog/2014/aug/06/ffa-cup-shines-its-light-on-tasmanias-proud-football-tradition

Reading it now, years later, I feel the nerves again. I also feel how quickly the light moves on. The competition endures. The pride endures. The questions about infrastructure, compliance, and what follows the moment have endured too.

Hope Economics

Why clubs keep betting on seasons that don’t add up

There comes a point, after enough years in football, where you stop asking whether something is possible and start asking whether it is probable.

I find myself there more often now.

Not because I’ve lost belief in football, but because I’ve watched too many clubs, run by good people, make decisions that only make sense if you believe that this season will be the one that breaks the pattern.

This post is about men’s football.

I’ll write about the women’s game separately, because it deserves its own lens.

This is not about ambition.

It’s about hope.

And how hope, in men’s football, becomes an economic model.

A quick explainer

At the top level of men’s state football sits the NPL, the highest tier available in Tasmania. Clubs don’t simply enter it. They are licensed to participate.

That licence comes with financial cost, administrative workload and ongoing compliance obligations. It assumes organisational depth, volunteer capacity and the ability to absorb risk.

Entry itself is expensive.

Holding a licence, meeting compliance standards, staffing match days, maintaining facilities, and delivering what is expected at the top tier requires significant resources before a ball is kicked. Add player payments on top and clubs are committing large sums of money and time with no guarantee of return.

This is not incidental.

It is foundational.

Winning the league does not cover the cost of entry.

Prize money is shared, limited and symbolic.

Which leads to the obvious question.

Why do clubs still pour money into it?

What I’ve seen, up close

Over the years, I’ve watched men’s clubs move in and out of the top tier.

Some lost a benefactor and could not replace that support.

Some merged because the numbers no longer stacked up.

Some simply ran out of people willing to carry the load.

Others chose to stay where they were. Not because they lacked pride but because they understood their limits. They knew what they could staff, fund and sustain.

I’ve seen boards change and priorities shift.

I’ve seen ambitious seasons followed by quiet resets.

I’ve seen clubs chase one last push and clubs choose to step back before the push broke them.

None of it was simple. None of it was clean.

What struck me, over time, was how often the same logic appeared underneath very different decisions.

Hope that the next season would unlock something.

Hope that success would stabilise the club.

Hope that the strain would ease once a target was reached.

Sometimes it did.

Often, it didn’t.

Hope as a business case

Most clubs don’t enter a season expecting to lose money.

They tell themselves

a good Cup run might offset costs

success might attract a major sponsor

crowds might lift

visibility might unlock something bigger

next year will be different

This is not delusion.

It’s hope.

But when hope becomes the justification for repeated financial risk, it stops being optimism and starts becoming an economic strategy.

A fragile one.

Spending to stand still

One of the quiet truths of elite men’s football is that spending is often not about moving forward.

It’s about not slipping back.

Clubs pay players to

hold position

protect reputation

avoid being read as declining

stay serious in the eyes of others

This is not reckless. It’s defensive.

But defensive spending is still spending and it rarely builds anything durable underneath.

When finishing first or last changes very little

There is another question that sits underneath all of this and it’s one I keep coming back to.

In a system without promotion and relegation, what does it actually mean to finish first or last?

You don’t go up.

You don’t go down.

The licence remains.

The costs remain.

The obligations remain.

So the stakes become symbolic rather than structural.

I’ve long been an advocate for promotion and relegation, not because it’s dramatic, but because it gives meaning to position. It creates consequence. It rewards sustainability as much as ambition.

Without it, winning becomes a statement rather than a step.

And that’s where the economics become harder to justify.

If finishing first doesn’t materially change your future and finishing last doesn’t force a reset, then the question naturally follows.

Why are we spending so much?

Is it for progress, or is it for pride?

Is it for pathway, or is it for proof?

Is it to build something, or simply to say we won?

None of those answers are inherently wrong.

But when the cost of chasing that answer includes financial strain, volunteer exhaustion and long-term fragility, it’s fair to ask whether the reward matches the risk.

Hope thrives in systems where consequence is blurred.

Promotion and relegation doesn’t remove hope.

It sharpens it.

The short-term season problem

An eighteen-game season sharpens this dynamic.

With limited matches

pressure on results increases

patience decreases

rotation narrows

depth becomes harder to manage

Paying players feels like insurance against a short runway.

But insurance only works if the risk is occasional, not structural.

The invisible subsidy

Here’s the part that rarely gets named.

Most clubs are not gambling with spare cash.

They are gambling with unpaid labour.

Every dollar spent on player payments usually requires

more administration

more fundraising

more compliance work

more emotional load carried by fewer people

The financial loss is visible.

The human cost is quieter.

And it accumulates.

Why walking away feels impossible

For some clubs, stepping back is unthinkable.

Not because the numbers don’t make sense, but because identity is tied to status.

Being top tier becomes who the club is, rather than where it happens to play.

So the question becomes

How do we stay here?

Not

What does this cost us?

Hope fills the gap where strategy should sit.

Two doors that keep the hope alive

There are genuine prizes on offer in men’s football.

One is open to everyone.

The Lakoseljac Cup allows any club, at any level, to make a run, to test itself, to dream.

The other is narrower.

Win the league and you earn scheduled games against interstate opposition in the Australian Championship.

Benchmarking.

Visibility.

Proof.

Those opportunities are real. They matter.

But they are also rare.

And rare outcomes are a dangerous foundation for regular spending.

When hope crowds out honesty

Hope is not the problem.

Football needs hope.

The problem is when hope replaces honest conversations about

sustainability

volunteer capacity

financial exposure

long-term purpose

When clubs feel they must keep rolling the dice simply to be taken seriously, something has gone wrong in the system.

A quieter definition of ambition

After many years watching seasons come and go, I’ve come to believe this.

Ambition is not how much you spend.

It’s how long you last.

It’s whether the club still recognises itself after leadership changes, after a bad season, after the noise fades.

Hope belongs in football.

I’m less convinced it belongs in the balance sheet.

The question underneath it all

I often wonder whether the biggest gamble in football isn’t losing matches.

It’s continuing to bet on seasons that don’t add up, because we’re afraid to imagine a different way of being ambitious.

Hope is powerful.

But hope, on its own, is not a business model.

And perhaps the bravest decision a club can make is not chasing the next breakthrough, but choosing a future it can actually sustain.

He was our Kenneth

Ken at Aston Villa

Part One: Copley

Copley, 1947

He was born Kenneth Morton on 19 May 1947.

No middle name.

At home, Eddie and Edna called him Kenneth. Outside the house, particularly in the North East of England, he was Kenny.

He was our Kenneth.

Copley was small. One road through the village. Farmhouses set back off the lane. From the very top to the very bottom, barely a kilometre. Quiet enough that you noticed sound when it arrived.

When Ken talks about it now, he says it reminds him of All Creatures Great and Small. That same sense of countryside calm, of people knowing one another, of space to roam.

Sundays were special. Copley Sunday meant picnics, family together and football on any bit of grass that would allow it. Cousins were there. Neville and John Chapman. Neville would later play for Middlesbrough, but back then he was just older, fitter, someone to chase in the summer holidays.

Copley felt safe. Friendly. A farming community where people said hello, where they noticed if you didn’t have your ball with you. There were only one or two shops at first, a Co-op later. A handful of council houses. Not many children. Five-a-side or six-a-side at most. If the ball went over a wall, nobody complained.

Ken was an only child. Well looked after. Well cared for.

He was born in a terraced house, two or three in a row of five. There was a yard and across the driveway a patch of grass. Enough space to juggle, to practise, to wear the ground down. To have a kick without troubling anyone.

Eddie was a busy man. He ran a garage and helped the local farmers. Edna was kind and loving. Like most households of the time, it was disciplined and structured, but Ken never got into trouble. He was always playing football.

Their first house had a backyard. Over the lane was an allotment. That became another place to play. When they later moved to Copley Lane, there was a hot bath ready when he came home muddy and tired. Boots left at the back door. Football was never discouraged. It was simply part of life.

Ken remembers Auntie Effie and Auntie Gwenie, his aunties by marriage. Gwenie was a Sunderland supporter, so football talk and football history were always around. His dad was friendly with Gordon Coe, president of Evenwood Town Football Club. At the time, the club was bringing players in from the army barracks and Eddie spent a lot of time driving and picking them up. Football, again, was just there. Woven in.

One of Ken’s earliest football memories has never left him.

He would have been eight or younger, at a match between Evenwood and Bishop Auckland. The legendary Bob Hardisty was carrying the ball out of defence when Ken ran under the wooden barrier and took it cleanly off him.

He didn’t get into trouble. The Evenwood crowd applauded. Bishop Auckland supporters were less impressed, the tackle stopping the start of an attack. Hardisty looked shocked, then smiled. Ken remembers him coming over afterwards and shaking his hand.

He doesn’t think his dad was with him that day. He thinks he was on his own.

Football never arrived in Ken’s life. It was always there.

Other boys went to the beck, the stream that ran nearby, or into the woods. Ken went with the ball. Always with the ball. He can’t remember getting his first one, only that he always had one.

After school was his favourite time of day. Three o’clock. Dribbling in and out of the white lines painted on the road home, then straight up to the recreation ground. He walked to school every day, ball under his arm, even though there was a bus.

Breakfast was simple. Cornflakes. His favourite meal was beans on toast. Still is.

Winters could be harsh. Snow covered the roads. His dad would clear them with the plough, and Ken would jog behind it on the way to school. If the driveway was blocked, it was cleared so he could have a kick. Weather rarely stopped him.

He wore sandshoes most days, boots for football. They weren’t brilliant. Wet Saturdays were just Saturdays in the North of England. The sound of the ball on stone walls was a dull thud. His mother always knew where he was.

If he couldn’t get out, he read. Football annuals. Football cards. Licking his fingers to turn the pages while waiting for the chance to play again.

Television was black and white. Match of the Day on Saturday nights showed him new things. Different goals. Players running with the ball. Diving headers. The next day he would be out practising what he’d seen, alone if necessary, becoming Tom Finney or Stanley Matthews in his own mind.

He was good at other sports. Decent at cricket. A strong tennis player. A very good athlete. He won the 100, 200 and 400 yards at school. But none of it competed with football.

While other boys his age played in the woods, Ken, six or seven years old, played football with older boys at the rec. He was always challenged. Losing taught him resilience. When something went wrong, he worked harder. Got the ball out and battered it against the wall until it felt right again.

He didn’t talk much on the pitch. He let his football do the talking. He wasn’t a bragger. He was loved in the village. People noticed him without making a fuss.

He was never lonely. There was always a ball.

Looking back now, he says football was everything to him.

“If I look at it now,” he says, “it was like a marriage.”

When asked where home feels like now, he says it’s where we live today. But when we watch English television and he sees a village, a lane, a patch of countryside, he still says, smiling, just like Copley.

Copley gave him space.

Family gave him security.

Football gave him direction.

This is where the story begins.

Why Football Isn’t Covered

A media and ownership explainer

Remembering a different paper

I remember a time when football appeared more often in the local paper.

Not just finals.

Not just opening rounds.

Ordinary weekends, with local results and familiar names.

That memory isn’t nostalgia.

It reflects a different media structure.

When The Mercury was locally owned

For much of its history, The Mercury was owned and operated locally by Davies Brothers. Editorial decisions were made in Hobart, by people who lived in the community the paper served. Local sport mattered because local life mattered. Football sat naturally alongside cricket, bowls, racing and school sport as part of the weekly rhythm.

People like Walter Pless, a teacher by profession and a long-time football writer by passion, contributed regular football coverage over many years. His work reflected what actually happened across Tasmanian grounds each weekend and was widely respected within the football community.

The ownership shift

That structure began to change in the 1980s.

Ownership shifted first to the Herald and Weekly Times, and later into the News Corp Australia stable. This was not a moral turning point. It was a structural one.

National ownership brought economies of scale, syndicated content and different priorities. Editorial focus increasingly aligned with sports that carried national commercial value and broadcast relevance. Coverage flowed towards codes that delivered audience, advertising and subscription return across multiple platforms.

Newspapers and broadcast working together

This is where the link between newspapers and broadcasting matters.

For many years, News Corp newspapers and Foxtel sat within the same commercial ecosystem. Newspapers didn’t just report on sport. They promoted broadcasts, previewed matches, amplified commentary and reinforced which sports were worth watching on television. Coverage and promotion worked in the same direction.

This didn’t require instruction or pressure.

The incentives were already aligned.

Sports like the Australian Football League and elite cricket are not just games. They are media products. Regular coverage supports broadcast value, drives subscriptions and keeps audiences engaged between matches. It is efficient, repeatable content.

Why football sits outside that system

Football, particularly local and community football, sits outside that ecosystem.

It is fragmented.

It spans multiple competitions and age groups.

It is played across dozens of grounds at overlapping times.

It produces participation at scale, but little broadcast leverage.

From a production perspective, it is difficult and expensive content for a shrinking newsroom.

An OTT and broadcast rights perspective

I studied OTT platforms and broadcast rights as part of my AFC coursework. In football-first countries, domestic football anchors the entire media economy. Broadcast platforms exist because football drives subscriptions. Coverage follows naturally.

Australia is different.

We have multiple football codes competing for attention. Legacy media aligned early with some and not others. Those alignments hardened over time.

Legacy influence is the momentum of past decisions. Once a sport dominates coverage for long enough, it begins to feel normal, expected, and permanent. That dominance is reinforced by habit, advertising relationships and audience expectation.

Football arrived late to that system and never fully integrated into the commercial media model.

That does not make football small.

It makes it inconvenient.

But football does get coverage

It is worth saying that football does still receive coverage.

National competitions like the A-League are reported on. The Socceroos and Matildas receive attention, particularly during major tournaments. And football is never absent when there is a scandal, controversy or an opportunity to critique fan behaviour.

But this is not local coverage.

It is national, episodic and easily accessible online. It does little to reflect the weekly reality of football in Tasmania, where hundreds of games are played every weekend by juniors, women, men, referees, coaches and volunteers who rarely see themselves acknowledged.

Personally, I find myself less engaged with the A-League now than I once was. Too many years were spent hoping, pushing and waiting for Tasmania to be meaningfully included. The absence of consistent local coverage also means fewer eyeballs on screens, fewer subscriptions and less perceived value added to broadcast rights. In that context, it is hard to ignore the uncomfortable possibility that this very invisibility is part of the reason Tasmania may never be seen as commercially viable for inclusion.

That distance has changed how I consume the game, but it hasn’t changed how deeply football exists here.

A changing broadcast landscape

More recently, Foxtel moved into new ownership under DAZN, a global streaming platform focused on efficiency, scale and return on investment rather than tradition or cultural legacy. Expensive domestic rights are now assessed through a different commercial lens.

What that means long-term remains to be seen. Ownership changes do not guarantee change. But they do loosen assumptions that once felt fixed.

Not ideology, but structure

I am not a fan of Rupert Murdoch or the political influence his media has exerted over decades. But this is not an argument about ideology. It is an explanation of how ownership, commercial alignment and broadcast strategy shape what is visible and what quietly disappears.

Football did not stop happening.

It stopped being seen.

How football adapted

So football adapted.

At many clubs, media and communications have become near full-time roles. Content is produced to keep sponsors engaged, promote attendance, document participation and tell stories that would otherwise go untold. Websites, social media, newsletters, photography and video now sit alongside coaching and administration.

This is not self-promotion.

It is survival.

A small personal ritual

I still subscribe to The Mercury.

Partly out of habit.

Partly out of loyalty to local journalism.

And partly, if I am honest, just in case.

Most days I skim straight to the back. I flick through the last pages, not really reading, just checking. Looking for a scoreline. A name. A photograph that suggests football has slipped back in.

It rarely has.

That small ritual probably says more than any media analysis. Coverage doesn’t just inform. It trains expectation. And over time, even those of us deeply involved in the game stop expecting to be seen.

Why this matters

This is not a plea for more coverage.

It is a 101 explanation of why coverage looks the way it does.

And perhaps a reminder that what is not reported still matters, still exists and still deserves to be remembered.

Goodbye 2025. Welcome 2026

One of Nikki’s fab photos

I want to write this down in case I forget.

Not the events, they are easy enough to list but the texture of the year. How it felt to live inside it.

2025 was a big year for me.

Stepping away

I stepped away from the Presidency of South Hobart Football Club after seventeen years. That sentence still lands heavily. Not because I regret the decision but because it marked the end of a long season of responsibility. The kind that seeps into your thinking and stays there long after the meetings end.

I am still learning who I am in football without a badge or a title attached.

Ken stepped back too, giving up senior coaching roles after more than fifty years in football. Watching someone who has shaped his entire adult life around the game feel a little lost has been confronting. There is grief in that, even when the decision is right.

We are learning, together, what it means to still belong without being central.

Max left for Melbourne, chasing opportunity and growth in his coaching. That was a proud moment and a tender one. You don’t spend decades building something as a family without feeling the pull when one of you needs to step beyond it.

I am glad he went. I miss him too.

The joy alongside it

The trips away this year were genuinely fun. Nikki came with us and at one point Ken said he felt like he was travelling with two wives. He was constantly fussed over, checked on and looked after.

It became a running joke but there was something quietly lovely in it too.

Those trips were for Australian Championship games, Wollongong, Marconi and Heidelberg. It was fabulous to see other clubs competing in the NPL system and to experience the level they operate at.

The gap is not huge. The football certainly isn’t. The money, perhaps, is.

Those shared moments, away from home, reminded me how much joy still sits alongside responsibility.

Building and sustaining

Ned continued to do an outstanding job as Academy Director, providing consistency, structure and calm leadership. He has been trusted by players, parents and coaches alike and the Academy numbers this year reflect that.

Parents are choosing organisation, professionalism, certainty and child safety for their children and they are prepared to pay for it. That tells its own story about where community football is heading.

Pete Edwards joined South Hobart Football Club and Morton’s Soccer School later in the year, after what he described as the longest interview process he had ever experienced for a coaching role.

His arrival added depth and energy to the program and complemented the foundations already in place.

On the field, the club competed in the Australian Championships. We travelled to watch them play. We hosted powerhouse clubs at home. We welcomed South Melbourne to KGV in the Australia Cup after winning the Lakoseljac Cup.

There were moments when I stood back and simply took it in.

Not pride exactly. Something quieter. A sense of perspective.

Nick won a third Best Player award this year. Three in a row. Watching that level of consistency, professionalism and resilience never gets old. He goes about his football with standards that don’t waver.

He also fielded offers from clubs in Tasmania and interstate. Recognition like that doesn’t happen in isolation. It is earned over time, through work, behaviour and care for the game.

The work and the weight

I also want to acknowledge the Board of South Hobart Football Club. Working alongside them this year has been one of the quiet strengths of 2025.

They love the game as deeply as I do and they carry that love with resilience and care.

Over the past two years we worked relentlessly on our bid for inclusion in the Australian Championships as a foundation member. The volume of work was immense. There were knockbacks, moments of limited support and long stretches where it felt like we were carrying the weight alone.

We can pretend that being knocked back is fine.

We can rally, regroup and carry on.

But the truth is, it wears you down.

There was a familiar feeling too. The here we go again sense of coming close, of almost making it, of being asked to prove ourselves one more time. It exposed divisions in the game that are hard to ignore.

And yet, through all of it, the Board remained engaged, principled and committed. That kind of resilience doesn’t happen by accident. It is earned, collectively, over time.

There was, however, one issue this year that cut deeply. It wasn’t a football issue, but it affected everything. It gnawed away at me and triggered a constant sense of unfairness, of asking, over and over, why is this happening to my club?

It tested my mental resilience in ways I didn’t expect and at times it was genuinely damaging.

Ten years of criticism and blame will do that to a person. Ten years of having to justify your existence, to answer every complaint directed at you.

Continuing as I was became unsustainable.

I’m not ready to name it yet, but I carry it with me into 2026 with clearer boundaries than before.

Scale and momentum

Both South Hobart and CRJFA continue to face the daily challenge of fitting thousands of children onto too few grounds. It is a constant exercise in compromise, goodwill and logistics.

Football is thriving. Participation is strong. Demand keeps growing. The system around it strains to keep up.

I would be remiss not to mention the Hobart Cup. The biggest Junior and Youth tournament in Tasmania (of any sport) and one that still takes my breath away each year.

In 2025 we held our breath over the weather, as always, knowing how much rides on a few days in September. This year it held.

Record numbers entered.

Record numbers attended.

Grounds full from morning to night.

Kids everywhere.

Families everywhere.

It was a fabulous showcase of football and of what is possible when the game grows beyond what can realistically be run as a purely volunteer event.

There are signs of movement. A new building at D’Arcy Street. New lights at Wellesley. Projects that take years to materialise and even longer to advocate for.

They represent progress, even when it arrives slowly.

Looking ahead

Some of my favourite moments of the year are imagined ones, still forming. Sitting in the new clubhouse, hopefully in 2026, having a drink with Murray and looking out over a space shaped by decades of effort and belief.

I remain in awe of those who support the club financially and of those who turn up, quietly and consistently, to do the work that keeps football alive.

The people who make the whole thing function rarely ask to be noticed.

I have written a lot this year. To remember. To make sense of more than twenty years spent inside football, governance and community life.

Writing has become a way of choosing how I stay connected, without losing myself in the process.

As I move into 2026, I feel something I didn’t expect.

Optimism.

Not the glossy kind. Not optimism that ignores structural problems or hard truths. But a steadier sense that change is possible and that I can choose how close I stand to the fire.

So this is my goodbye to 2025.

A year of endings, shifts and recalibration.

And my welcome to 2026.

A year that feels open, lighter and full of possibility.

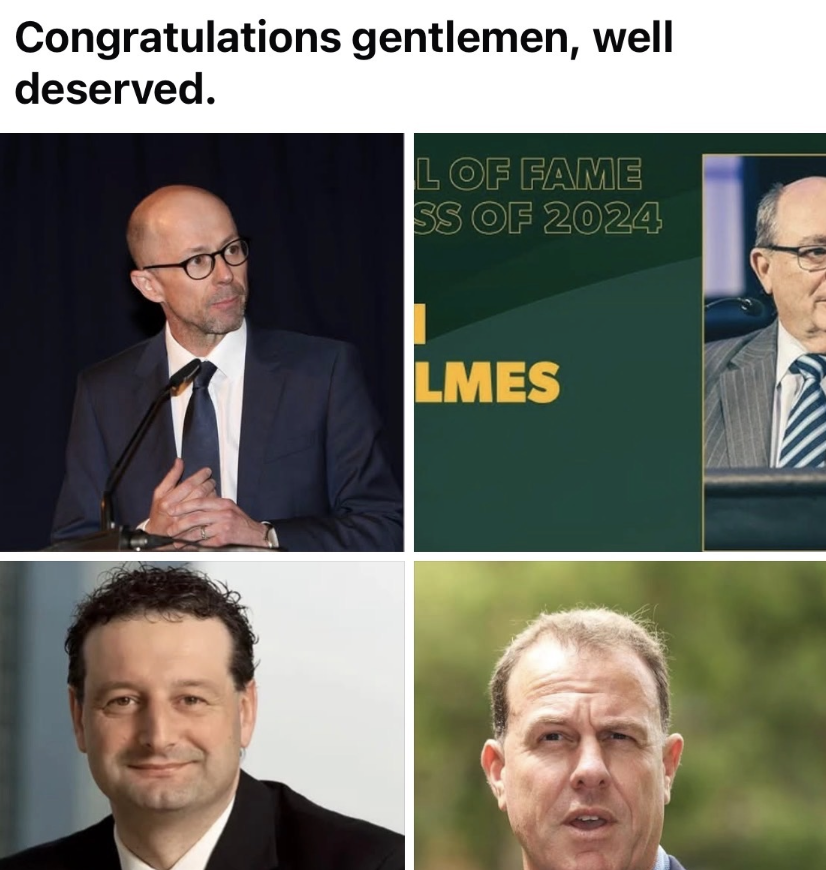

Football Faces Tasmania Peter Mies

Peter Mies at Launceston Juventus.

Photo: The Examiner.

I interviewed Peter Mies some time ago, never imagining I would one day be sharing his words after his passing.

Peter’s life in football spanned decades, continents, clubs, and generations. He played, coached, captained, administered, volunteered and supported the game in Tasmania for over sixty years. More than that, football was how he found belonging as a migrant, how he built lifelong friendships and how his family remained connected across three generations.

This interview is shared largely in Peter’s own words. I have resisted the urge to polish or rewrite them. What follows is not a tribute written about him but a record of how he spoke about the game he loved, the people who mattered most to him and the life football gave him.

What are your first football memories and did any particular person instil a love of football into you?

On the push bike early Saturday mornings in Holland, aged seven. Playing football in the snow. It did not matter what the weather, I just loved to play.

How long have you been involved in football and what roles have you played?

I have been involved for seventy-five years. I have been coach, captain, Tasmanian representative, president, life member. I am still Club Patron of Launceston Juventus, LCFC.

You name it. I have done it.

Tell us what football was like in Tasmania when you first got involved. Was it better, worse, different? How has it changed?

Many players were migrants that came from Europe. The standard was generally better, some teams were better for sure. The players are generally fitter now though.

Did you have role models or football heroes, or anti-heroes for that matter?

Didi, Garrincha, Pelé, Cruyff, Maradona, Messi.

How has football affected you and your family?

When I arrived in Tasmania as a migrant, it was great to have football here so that I could continue playing and continue my love of the game. It was a great way to meet new people and make new friends that also loved the beautiful game.

I have continued this love of the game in Tasmania for over sixty years in all capacities. I have been fortunate to be involved as a player and coach and to win every major trophy on offer in Tasmania.

Football has been a massive part of my family, going across three generations, starting with me and still going strong. I have been fortunate that my son Roger had a great career and I followed him very closely. I also have five grandchildren that have all played football and I have followed them all through their childhood.

Roger’s children, Noah and Ryan Mies, in Launceston, and my daughter Olga’s children, Sam, Zac and Olivia Leon, in Hobart.

I always went with Roger everywhere, including interstate to watch him play as a junior, and then through his senior career. I never missed a game.

I also went interstate to watch my grandsons Noah and Ryan play. I would be watching Noah and Ryan play every weekend in Launceston, and if I was not watching them, I would be in Hobart watching Sam, Zac and Olivia.

Noah, Newcastle Olympic, and Olivia, Clarence Zebras, are still playing. I watch Noah every week on TV on YouTube. I am still very black and white when I watch Launceston City play every week.

Football has given a lot back to me.

Which Tasmanians have affected your involvement in football, both on and off the field, and why?

The biggest influence on my football career has been my beautiful late wife, Christina. She stood by me in everything in life and supported me in every role I had in football.

Christina also became a very well-deserved life member of Launceston Juventus, LCFC, for the many years she ran the club canteen. I lost count.

She always made the hamburgers fresh by hand the night before, as well as organising everything for game day. She helped with any club activities and loved watching me, her son, and her grandchildren play.

She was a great supporter of Launceston Juventus, LCFC, and football in general. A true lady.

If you could make any changes to Tasmanian football, what would you do?

Some aspects of the administration of the game. With all the computers and the like these days, something that should be relatively simple, such as rostering, seems to throw up outcomes that do not make much sense.

The rostering seemed more straightforward when it was run by volunteers with a pen and paper.

Looking back on your football life, what do you think your legacy to the game in Tasmania might be?

I began an amazing family dynasty, where myself, my son Roger, and my grandson Noah are the only family in Tasmanian football history to have three consecutive generations play for Tasmania.

I have overseen the rise of Launceston Juventus as a football powerhouse in Tasmania and have been involved in winning every major trophy available in the state. We are the only club in the north of the state that have played in every year of the State League or NPL since the 1960s.

I have always been an advocate for improving the standard of football in Tasmania and was instrumental in bringing key import players to Tasmania, for example Peter Savill, Peter Sawdon and the Guest brothers. These players helped raise the standard of the game through their own playing quality, but also gave back to Tasmanian football and worked with local players and juniors so they could improve for the betterment of the game.

I am very proud to be the Club Patron at LCFC.

I always played the beautiful game with total passion and commitment, hard but fair. I have kept that philosophy in the way that I have lived my life.

In Football Nothing Has Happened Yet

Ken and I were watching football early one morning, coffee in hand, when the conversation drifted, as it often does, into goals.

When are they scored?

More in the first half or the second?

It is one of those simple questions that opens something bigger. Because almost immediately the familiar criticism surfaced, the one football always seems to carry.

“There aren’t enough goals.”

It is a comment most football people have heard countless times, usually from those more used to sports where the scoreboard is constantly ticking over.

Early mornings and plenty to watch

Perhaps it helps that we are watching a lot of football at the moment.

Early morning kick-offs suit us. The house is quiet. The day has not yet started. We can sit and watch properly.

Premier League.

AFCON.

The EFL Championship.

There have been plenty of goals, plenty of drama, and plenty of different game states to observe. And yet, even with all of that, it is not the number of goals that holds the attention. It is when they come and what they change.

The comparison problem

In Australia, football lives alongside sports like AFL, where a goal is worth six points and scores can climb quickly and dramatically.

There is movement on the scoreboard almost all the time.

Momentum is visible.

Reward feels constant.

Football does not work that way.

A typical match might finish 1–0, 1–1, or sometimes 0–0, and to some eyes that feels underwhelming. But that reaction often comes from measuring football against the wrong standard.

Football is not a high-scoring sport by design. It never has been.

Why low scores create tension, not boredom

In football, goals are rare. That is precisely why they matter.

A single goal can change everything.

A single mistake can decide a match.

A single moment can undo ninety minutes of discipline.

In a 0–0 game, nothing feels settled. Every attack carries possibility. Every defensive error feels dangerous. The longer the score stays level, the greater the tension becomes.

A 1–1 match can feel even tighter. Both teams know that one more goal may be decisive. Risk and restraint exist side by side, and every decision is weighed.

This is not emptiness.

It is suspense.

When goals are actually scored

When Ken and I went back to our original question, the answer was clear.

Across most leagues and competitions, more goals are scored in the second half than the first.

Just under half come before the break.

Just over half come after.

The final fifteen minutes of a match are consistently the most goal-heavy period of all.

This matters, because it explains why football often feels as though it is building rather than exploding early.

A quiet first half does not mean a dull match.

It often means the tension is still forming.

First half control, second half consequence

The first half in football is often cautious. Teams are organised, legs are fresh, mistakes are fewer. It is not unusual for a match to reach half-time scoreless. But this is not a failure of entertainment. It is the laying of foundations.

Most goals come later, when the game loosens and decisions become harder to execute perfectly.

Why the second half opens up

There are sensible reasons for this.

Fatigue begins to show.

Concentration slips.

Defensive structure becomes harder to maintain.

Game state matters too. Once a team is behind, they must take risks. Lines stretch. Spaces appear. Substitutions introduce fresh legs and new problems to solve.

Football rewards patience and punishes small errors. The longer the game goes, the harder perfection becomes.

Discipline still matters

How often have we seen it. A side that sits deep, absorbs pressure, defends for almost ninety minutes, and still finds a way to win.

Not by accident.

By discipline.

By holding shape when legs are heavy.

By saying no to the tempting pass forward.

By trusting teammates to do their job.

Those matches are often dismissed as negative or unattractive, but they are anything but. They are studies in concentration and restraint. They remind us that football is not just about attacking flair, but about collective resolve. Sometimes the most impressive thing a team does is refuse to break.

Where goals actually come from

Most goals are not scored from distance. They are not spectacular. They are not clean.

They come from inside the box.

From close range.

From cut-backs.

From second balls.

From moments when structure finally gives way.

Long-range goals live in the memory, but they are the exception. Football is designed around probability, not beauty. The closer you are to goal, the harder it is to defend perfectly.

This is why teams that sit deep can survive for so long. They are not just defending space. They are defending the most dangerous areas of the pitch. They are limiting probability.

When that discipline holds, the game remains tight. When it cracks, it often cracks suddenly.

Where VAR fits into all of this

This is where modern football complicates the conversation.

The introduction of VAR has led many to feel that football now has even fewer goals, particularly because of marginal offside decisions. Lines drawn so tightly that a shoulder, a knee, or yes, the nose of an attacker appears to cancel out the moment entirely.

Statistically, VAR has not reduced the total number of goals. In some competitions, goals have even increased slightly, largely because more penalties are awarded.

But numbers are not really what people are reacting to.

What VAR changed was how goals are experienced.

A goal used to be instinctive.

Now it is provisional.

The pause.

The wait.

The freeze-frame.

The lines.

When goals are already rare, taking one away, even correctly, feels enormous. Football is a low-scoring game built on flow and emotion. It was never designed to be judged frame by frame.

For a time, VAR chased absolute precision, and in doing so offended football’s sense of fairness. Most competitions have since softened that approach, quietly acknowledging that being technically right is not always the same as being true to the game.

Understanding football on its own terms

Football is often criticised for not offering constant reward, but that criticism misunderstands its nature.

The drama is not in accumulation.

It is in consequence.

Goals arrive less often, but when they do, they carry weight. They reshape the match, the crowd, and sometimes the season.

Perhaps that is why so many of us find ourselves leaning forward in the final stages of a game, even when the score is low. Especially when the score is low.

Because in football, nothing has happened yet.

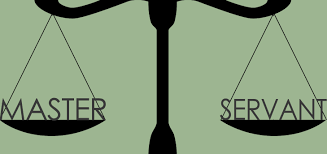

Master and Servant - paying to be Governed

There is an uncomfortable dynamic at the heart of football governance that we rarely name.

Clubs fund the system.

Governing bodies are paid to run it.

Volunteers deliver it.

Somewhere in that arrangement, roles blur.

We pay to be governed yet often feel unheard. Governing bodies are tasked with serving the game yet must exercise authority. Volunteers carry the workload, yet resist being directed. Everyone feels the tension, even if we lack the language for it.

With some distance from formal roles, and more time to reflect, the patterns have become harder to ignore.

That tension sits uneasily between two ideas.

Master and servant.

Paying to be governed

Football clubs do not sit outside the governance system. They fund it.

Affiliation fees.

Levies.

Licensing costs.

Compliance charges.

Money flows upwards. Clubs pay to participate. They pay to be regulated. They pay to be governed.

It is not unreasonable that payment creates expectation. When clubs contribute financially, they expect to be listened to. They expect decisions to reflect lived reality. They expect the burden to be understood.

This is not entitlement. It is a natural consequence of funding a system from below.

Authority and responsibility

Governing bodies, in turn, carry responsibility for the whole game. They are required to make decisions that apply broadly and consistently. They must balance competing interests. They must say no. They must absorb dissatisfaction.

They cannot please everyone. They are paid because someone has to hold that line.

This is where the relationship becomes strained.

Clubs experience decisions as distant or imposed. Governing bodies experience feedback as constant pressure. Both feel misunderstood.

Neither position is entirely comfortable.

The volunteer shield

Over the years I have heard the phrase many times.

You can’t tell me what to do, I’m a volunteer.

It is often said with conviction, sometimes with frustration, and sometimes with pride. Volunteering is a badge of honour. It signals contribution, generosity and commitment. It carries moral weight.

In many ways, it deserves respect.

But football no longer operates in a space where that statement is entirely true.

Volunteers are subject to rules, standards and decisions made elsewhere. Safeguarding frameworks, licensing criteria, governance requirements and compliance obligations apply regardless of whether a role is paid or unpaid.

Governing bodies can, in fact, tell volunteers what to do.

That reality sits uncomfortably alongside the deeply held belief that volunteering should come with autonomy.

Where it breaks down

This contradiction sits at the centre of much of the frustration in football.

Clubs pay to be governed, and expect to be heard.

Governing bodies are paid to govern, and must exercise authority.

Volunteers deliver the system, and resist being directed.

Each position makes sense on its own. Together, they create friction.

Money changes expectations. Volunteering creates resistance to control. Authority exists without ownership. Responsibility exists without power.

No one feels fully served.

Voice and being heard

Much of the tension plays out around voice.

Who gets to speak.

How they speak.

And whether speaking results in change.

AGMs, emails, committees and formal consultation processes provide opportunities to speak. They do not always provide the experience of being heard.

Being allowed to contribute feedback is not the same as shaping outcomes. When decisions are made elsewhere, or when consultation feels procedural, frustration grows.

The role of the CEO

In practice, the CEO often becomes the central figure in this dynamic.

Over many years as a club President, I dealt with a number of CEOs. Some listened well. Some did not. The difference mattered.

When the relationship worked, the role was manageable, even when issues were complex or decisions were difficult. When it didn’t, the role became significantly harder.

That is not because a President expects agreement. Disagreement is part of governance. It is because, when issues arise, the CEO is often the first and sometimes the only point of contact for clubs trying to navigate the system.

When you are a club President and problems emerge, who do you speak to within the governing body? Who helps interpret decisions, provide context, or offer advice when written rules do not neatly fit lived reality?

Boards are removed by design. Committees meet periodically. Formal processes are slow. The CEO becomes the conduit, the interpreter, the sounding board and sometimes the shock absorber.

In a small football state, this role carries particular weight. There are fewer layers, fewer alternative pathways and fewer places to go. When that central relationship functions well, tension can be absorbed. When it does not, frustration escalates quickly.

This is not about personality or popularity. Most people in these roles are trying to do the right thing. But in a small system, leadership style amplifies existing tension rather than containing it.

The cost of ambiguity

Football sits in an awkward space.

It is funded from below.

Delivered by volunteers.

Governed by paid professionals.

Roles overlap. Expectations collide.

Clubs feel like customers and subjects at the same time. Governing bodies feel like servants and masters at the same time.

This ambiguity is not accidental. It is structural. And it carries a cost.

Frustration.

Burnout.

Disengagement.

Mistrust.

It also leaves people carrying tension that is not theirs to resolve, long after meetings end and emails are sent.

For me, that sense of helplessness and the accumulation of frustration over many years, eventually became a factor in stepping away from formal leadership roles. Not because I stopped caring, but because carrying unresolved tension for too long comes at a personal cost.

None of these are caused by bad intent. They arise when systems outgrow the assumptions they were built on.

An unresolved tension

This is not an argument for less governance, or for unpaid administrators to carry more authority. It is not a call for blame.

It is an attempt to name a paradox.

Football asks clubs to fund the system, governing bodies to control it and volunteers to deliver it. Each role carries expectation. Each carries pressure.

Perhaps the real difficulty is not deciding who is master and who is servant, but acknowledging that the system asks all three to live with that ambiguity, every day.

When Football Outgrew the Volunteer Model

I was prompted to write this after sharing a recent Football Faces interview with Cathy James. She made a simple observation in passing, that football clubs now operate much like small businesses. It landed because it rang true.

It also explained a tension many of us feel but struggle to articulate.

For a long time, football clubs were spoken about as community organisations.

Run by volunteers.

Low cost.

Flexible.

That description once fitted.

It no longer does.

Modern football clubs now operate somewhere between amateur sport and professional enterprise. Expectations have shifted, quietly but decisively, while the structures beneath them have not.

Professional expectations, volunteer labour

Players expect to be paid.

Coaches expect to be paid.

Support staff expect allowances.

Families expect quality programs, safe environments, clear pathways and professional communication. Leagues expect compliance, reporting, licensing and consistency. Sponsors expect professionalism.

At the same time, boards remain unpaid. Canteens are staffed by volunteers. Administration is done after hours. The same six or eight people carry most of the load, year after year.

The tension is obvious.

It is also unsustainable.

Football clubs as small businesses

Whether we like the label or not, most football clubs now operate as small businesses.

They manage substantial budgets.

They pay wages and allowances.

They hire facilities.

They purchase equipment.

They insure people, assets and activities.

They manage risk.

They communicate, market and brand themselves.

Many clubs are registered for GST. They submit BAS statements to the ATO. They maintain financial records and manage cash flow. These are not optional tasks. They are legal obligations.

Clubs also apply for competitive grants, often to fund infrastructure, equipment or participation programs. Grant writing is skilled, time-consuming work. It involves compliance, reporting and acquittals and it carries real consequences if done poorly. This work is largely invisible and almost always unpaid.

Safeguarding and compliance

Child safeguarding alone has transformed how clubs operate, and rightly so.

Clubs are responsible for child safety frameworks, working with vulnerable people checks, education, reporting obligations and compliance. These are critical protections. They take time, care and administrative effort. They are not optional, and they are not light-touch responsibilities.

This work matters deeply. It also adds to the professional load carried by clubs that are still largely powered by volunteers.

Governance and responsibility

Boards are not symbolic. They carry legal and financial responsibility. Decisions have consequences. Compliance matters.

Many clubs are independently audited. Audits cost money but they provide assurance and transparency for boards, members and the wider community. They are part of operating responsibly.

This level of responsibility is one reason board positions are increasingly difficult to fill. It is not apathy. It is caution. People understand, instinctively, that being on a board carries weight, risk and expectation.

Trying to solve the volunteer problem

I remember many conversations over the years around a board table, asking the same question.

How do we tackle the lack of volunteers?

One suggestion was to ask families to staff the canteen once a season, shared across a team. On the surface, it seemed reasonable. Spread the load. Keep costs down. Maintain the volunteer model.

The response was mixed.

Some said they simply did not have the time.

Some said they would rather contribute financially instead.

Some felt it was unfair if everyone did not participate equally.

Some were willing. Some were not.

There was no solution that felt both fair and workable.

When consensus could not be reached, clubs returned to the only mechanism they reliably have.

Registration fees increased.

Bottom-up funding

Football is largely funded from the bottom up.

There are no major broadcast deals filtering down to community clubs. No television windfalls quietly underwriting participation. Football competes with AFL, NRL and cricket for broadcast money and commercial attention and it does so from a weaker position.

As a result, money flows upwards, not downwards.

Clubs pay affiliation fees.

They pay levies.

They pay licensing costs.

They pay to be governed.

Very little flows back.

NPL clubs, in particular, sit in an uncomfortable twilight zone. They are expected to operate like small businesses, with professional standards, paid staff and significant compliance obligations, yet because they are sporting clubs they are often ineligible for small business grants and support. They carry the costs of professionalism without access to the systems designed to support it.

This is not a complaint. It is a structural reality. But it matters when football is criticised for its cost without acknowledging how the game is actually funded.

The shrinking volunteer pool

The volunteer model has also collided with social change.

Two-income households are now the norm. Women work. Evenings are full. The cost of living is higher than ever. Time is scarce.

The old assumptions, mums in the canteen, dads on the committee, no longer reflect how families live. Yet clubs are still expected to function as though that labour will simply appear.

It doesn’t.

Football is expensive

Football is often accused of being expensive. That criticism is not always wrong, but it is rarely placed in context.

Benchmarks are higher than ever. Safety standards, coaching qualifications, facilities, insurance, compliance, communication and expectations have all risen. Clubs are expected to deliver professional experiences while charging community prices.

When volunteer labour cannot be guaranteed and funding does not flow down, costs do not disappear.

They shift.

How boards are really filled

When board vacancies arise, there is rarely a queue. Positions are filled through personal approaches. A tap on the shoulder. A familiar name.

This is often framed as exclusivity or power retention. More often, it is survival.

Clubs do not struggle to find people who care. They struggle to find people who can carry the responsibility, the workload and the time commitment without breaking.

The question we keep avoiding

If football clubs are already operating as small businesses, perhaps the real question is not why volunteers are disappearing, it is why we continue to design systems that rely on unpaid labour, while funding flows only one way?

How many games do top men’s teams actually play

And what Tasmania’s numbers quietly reveal

This post follows an earlier reflection on minutes, squad management and the lived reality inside short seasons. Together, they form part of an ongoing attempt to understand how the structures we build shape the football we end up with, not through blame or solutions but through observation.

After writing about minutes, squads, and the lived reality inside an eighteen-round season, I wanted to step back and look at something simpler.

How many league games senior men’s teams actually play.

Not best-case scenarios.

Not finals.

Not cup runs.

Just the base number of guaranteed competition matches a league provides.

When you line Tasmania up against the rest of Australia and then against the football world more broadly, the gap becomes hard to ignore.

Where Tasmania has been, and where 2026 sits

For many recent seasons, NPL Tasmania has been an eight-team competition playing a triple round robin.

That structure delivered 21 league matches per club and it became the accepted shape of a senior season in this state.

In 2026, that changes.

Football Tasmania has confirmed the men’s NPL will expand to ten teams but the regular season will reduce to eighteen rounds, followed by finals.

At the end of the season, the competition will contract back to eight teams, with the bottom two finishing clubs removed for 2027.

There has been no indication that promotion and relegation will operate beyond this one-off reset.

This matters, because what is being introduced is not long-term movement between tiers but a tightening of access combined with fewer guaranteed games.

How Tasmania compares to other small federations

It is often assumed that Tasmania’s shorter season simply reflects being a smaller federation.

The numbers do not support that.

In the 2025 season, senior men’s NPL competitions in other smaller or comparable federations played:

South Australia: 22 league rounds

Northern NSW: 22 league rounds

Western Australia: 22 league rounds

Tasmania itself played 21 rounds in 2024 and 2025.

Even the smallest NPL federations, such as the ACT, have historically delivered around 21 league matches per season. The Northern Territory operates outside the NPL structure and is not a like-for-like comparison.

So this is not a case of Tasmania always operating at the low end.

In 2026, Tasmania will deliberately reduce its top tier to 18 league matches, placing it below every other NPL competition in the country, including federations facing similar logistical challenges.

Eighteen games in a national context

Across Australia, senior men’s NPL competitions typically provide:

26 league games in Victoria

30 league games in New South Wales

Same country.

Same national competition framework.

Very different assumptions about what constitutes a senior season.

Eighteen league games does not sit at the lower edge of a wide range.

It sits below it.

What the world considers normal

Internationally, the contrast sharpens further.

In most established football countries, top-tier league seasons are built around:

38 league matches in England, Spain, and Italy

34 league matches in Germany and France

That is the league alone.

Domestic cup competitions sit on top of that foundation. They do not replace it.

Players live in rhythm.

Week after week.

Enough repetition to absorb mistakes and recover form.

Even Australia’s professional tier operates on a larger base.

The A-League Men provides 26 regular-season matches before finals.

So when we describe the NPL as the highest level of senior football in Tasmania, it is worth being honest about the comparison.

Our top state league offers fewer guaranteed league matches than almost every comparable competition, nationally and internationally.

What a credible benchmark actually looks like

This is not about pretending Tasmania should mirror Europe.

But there is a reasonable middle ground.

Nationally, 22 to 26 league matches is already considered normal for senior NPL competitions. Internationally, anything under thirty is viewed as light.

Against that context, eighteen is not just conservative.

It is structurally limiting.

Decisions about competition length are often framed as unavoidable. In reality, they reflect choices about what level of strain the system is prepared to absorb.

If we are serious about development, retention and performance, the benchmark should at least sit within the national NPL range, not below it.

Quality opposition changes standards

This is not theoretical.

Having recently played NPL clubs such as Marconi Stallions, Wollongong Wolves and Heidelberg United, the difference in tempo, pressure and decision-making was evident.

These are clubs coming out of much larger league programs.

In 2025:

Marconi and Wollongong Wolves each played 30 league matches in NPL NSW

Heidelberg United played 22 league matches in NPL Victoria

State cup competitions then sit on top of that base:

NSW clubs contest the Waratah Cup, typically adding several knockout matches depending on progression

Victorian clubs contest the Dockerty Cup, where Heidelberg’s run to the final added six additional high-quality games

Tasmanian clubs, by contrast, are operating in a system that delivered 21 league matches in recent seasons, dropping to 18 in 2026, with the Lakoseljac Cup layered on top.

The difference is not talent.

It is exposure.

More league games mean more repetition under pressure, more consequences and more opportunities for standards to harden.

When players are regularly tested, standards rise.

When they are not, progress is slower.

What this gap means for Tasmanian football

The consequences are not abstract.

They show up when Tasmanian teams step into national tournaments.

They show up when players trial interstate.

They show up when coaches try to bridge the gap between strong training environments and elite match demands.

Players are not underprepared because they lack effort.

They are underexposed.

The ceiling for Tasmanian football is shaped less by talent than by how often that talent is tested under genuine pressure.

Cup competitions add games, but not certainty

Cup competitions matter.

Tasmanian clubs contest the Lakoseljac Cup.

Interstate NPL clubs contest the Waratah Cup (NSW) and Dockerty Cup (Vic).

But these are knockout competitions.

For some clubs, a cup run may add several matches.

For others, it may add one game and then elimination.

Cup football is unpredictable by design.

It cannot be relied upon to provide consistent match volume across a squad, across a season, or across a league.

At best, cups supplement a strong league calendar.

They do not replace one.

A long-standing alternative that never quite landed

For many years, while I was president of SHFC and with the continuous encouragement of Ken Morton as senior NPL coach, we advocated for a four-round season with eight teams.

A true double home-and-away, played twice.

Equal.

Predictable.

More games.

Four rounds would have delivered 28 league matches, while maintaining competitive balance.

The pushback was familiar.

Volunteer burnout.

Travel.

Ground access.

Capacity.

Those concerns are real.

But they now sit alongside another reality.

Clubs at this level increasingly operate as small businesses, managing compliance, facilities, staff, academies and year-round programs. (Plenty of material for a standalone blog post here)

Adaptation is already happening, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Football’s place in the sporting ecosystem matters

There is another layer to this.

In many countries, football is the dominant sport.

It shapes calendars, ground access, and scheduling priorities.

Australia is different.

Football here is one of many sports competing for finite resources. Grounds, volunteers, council priorities, media attention and funding are shared with codes that are historically dominant and deeply entrenched.

Football is often fitted into available windows rather than planned as the organising framework.

The outcome is predictable.

Shorter competitions.

Compromised calendars.

Reliance on workarounds.

This is not about ambition or size.

It is about alignment between what we call elite football and how we structure it.

What this follow-up is really saying

The first post was about minutes and people.

This one is about scale, quality, and intent.

Tasmania’s top men’s competition now sits:

Below other small federations nationally

Below the broader NPL standard

Well below professional and international benchmarks

At the same time, access is being tightened and consequences increased.

Fewer guaranteed games.

Higher pressure.

Limited exposure to elite opposition.

If standards are to rise, the pathway is not mysterious.

More high-quality games produce better football.

The number of games a league schedules tells you exactly how serious it is about development, retention and performance.

And right now, eighteen does not say what we think it says.

Football Faces Tasmania - Cathy James

Cathy James

Cathy James has moved on from Kingborough Lions now, but she remains one of the truly inspirational volunteers we interviewed.

Hard-working, dedicated, and quietly effective, Cathy is the kind of person every club relies on and rarely celebrates. She did not see her contribution as anything special. She simply showed up, again and again, and did what needed to be done.

This interview captures Cathy’s story in her own words, and reflects the care, commitment, and generosity that underpin community football in Tasmania.

Tell us YOUR story about how you became involved in football and what you love about the game and the community:

My “Football Story” is not one of wanting to be a Matilda – there were no Matildas in the 1970s. It is not one of having a “football hero” and following their career. My involvement in Football is an accident.

Growing up in Oakville, a tiny town (it had a school and a fire station) on the outskirts of Sydney. The readily available team sport option for girls was Netball. And yet, funnily enough, Matilda, Courtney Nevin, went to the same Primary School and played for the Oakville Ravens – which just shows how rapidly things can change in the world of Football.

My first Football memory is: “thank goodness, a sport other than netball”. Arriving at High School I discovered there were other amazing sports – hockey, cricket, volleyball and soccer. Soccer as it was still know then, didn’t rate highly against the other football codes, Rugby Union and Rugby League, and it was only played by English and European immigrants. However, soccer could be played by girls. There was one InterSchool Tournament per year and while I wasn’t a shining star, I was committed.

My real involvement in football began when I wanted my kids to play team sport – I chose Football. It was a sport I had enjoyed and it is also a sport that anyone at any age can play – it’s running; there is limited throwing or catching. With 3 kids playing for Kenthurst Soccer Club I put the boots back on and that was 20 years ago. And, in the meantime, 2006 FIFA World Cup and all of Australia fell in love with Football and the Socceroos.

The thing about sport is it’s a bridge-builder. When you relocate, whether it’s across town or to a new state, you can join a sporting club and you’ve got something in common with people in the community. 15 years ago, the family moved to Tasmania, into the Kingborough region, joined Kingborough Lions United FC and never left – well that’s 4 of us. Even after all these years, I cannot convince my husband of the merits of the round ball game.

While the game of Football has many highs and lows being involved in a Club can support people through their highs and lows. While in my playing days, I have often been described as “uncoachable”, I have always given 100% effort, pretty much like now as a volunteer. And, dare I say it, my best game of Football was played a few days after my Dad died fully supported by my Football family.

Another thing about being involved in a Not-For-Profit Community Sporting Club is, that without volunteers and money they don’t thrive. I have a lot of a “can do” attitude and my daily mantra is “how can I make a difference today”. I have been a player, a team manager, the Club Secretary/Adminstrator/Registrar, Kiosk Manager. I have enjoyed all the benefits of being a player – coaching, equipment, playing strip, facilities, so for me it’s a natural progression to “give back”. Registration fees do not cover all the costs required if Clubs were to pay people to do all the activities it takes to get teams on the park and down here in Clubland there are plenty of inspirational people to keep you going.

At Kingborough I’ve been lucky to play with and work with some incredible people. There are families here that have had multiple generations come through and I’m sure there are other Clubs that have benefitted from the same thing. The list of people in Tasmanian Football that inspire me is endless. Bernie Siggins was an amazing “can do and will do” man and was a true inspiration to all players and volunteers at Kingborough Lions United FC. Brian & Jill Dale truly love and care for their Club and have put years of time and energy into it. I know each Club has role models like these and they don’t do it for the acknowledgement they “just do it”.

Football in Tasmania is rapidly changing. Community Clubs are having to comply with regulations – food business, RSA, workplace health & safety, and recently COVID-19.

Clubs are small businesses with massive interests in their communities. We currently have 2 Clubs vying for selection to be WWC 2023 Base Camps; we’re building towards having A-League and W-League teams. Football has massive participation across males & females. It is a great time to be involved in Football in Tasmania. And, it is a great time to be a Volunteer in Football in Tasmania.

Do you want to join the Board of Football Tasmania? Here is how

Governance is often dismissed as boring. Paperwork. Process. People in rooms talking in circles.

And sometimes, honestly, it is.

But governance is also where decisions are made, power is exercised and priorities are set. If you care about football, eventually you run into governance whether you want to or not. Understanding it is not about enjoying it. It is about knowing how the system you are part of actually works.

Who this is for

This post is for anyone who has ever said they are unhappy with the way football is governed in Tasmania and wondered what, realistically, they could do about it.

One option, often spoken about but rarely explained, is joining the Board.

So here is how that actually works.

Not in theory.

Not in whispers.

In practice.

Who actually elects the Board

The Board of Football Tasmania is not elected by the football public. There is no popular vote. Parents, players, coaches and volunteers do not vote directly for Board members.

The Board is elected by members.

A member is not an individual. A member is a recognised body, usually a club, a regional association or a formally recognised committee, acting through an authorised representative. That representative votes on behalf of their organisation.

Most individuals involved in football are not members in a governance sense. Their club or association is the member and it votes through a delegate.

This matters, because it means being well known or well liked is not enough. Support has to be built at an organisational level.

Getting nominated

If you want to be elected, you must first be nominated.

Nominations must be made formally. They require proposers and a seconder who are themselves members or directors. They must be submitted by a specified date and include statutory declarations about conflicts of interest and suitability.

This is not casual. It is designed to be deliberate.

How voting actually works, Borda Count explained

If more people nominate than there are positions available, an election is held at the AGM. Voting is done using a preferential system known as the Borda Count.

If that sounds abstract, it is actually quite familiar.

Most football clubs already use a version of this every week. After a match, coaches or designated club people award three votes, then two, then one, for best on ground. Those votes accumulate across the season and at the end, the player with the strongest overall contribution is recognised.

The Borda Count works the same way.

Members rank candidates in order of preference. First preference carries the most weight, then second, then third. Those preferences are converted into points and added up across all ballots. The candidate with the highest total is elected.

It rewards broad respect rather than narrow support. A candidate who is consistently rated second or third by many voters can outperform someone who is first for a few and last for many.

Who is eligible and who is not

Eligibility is where many people come unstuck.

The constitution excludes people who hold certain operational roles within football. This is not personal. It is structural. The intention is to separate governance from day-to-day administration.

In a small state, that exclusion matters. Many of the most experienced people in football hold multiple roles. To stand for the Board, choices have to be made. Some roles must be relinquished.

That is uncomfortable but it is also honest.

The narrow exception for the President

There is a narrow exception relating to the President role.

In simple terms, it allows someone who has already served on the Board but not yet as President, to extend their service for continuity. It does not override conflict rules or eligibility requirements.

It exists to avoid constant churn at the top, not to create a loophole.

Elected directors and appointed directors are not the same thing

It is important to understand that not all Board positions are elected.