Governance + Politics

Vale Glen Roland

Thanks to South East for the photo. A perfect photo of Glen.

For Glen Roland, a Big Man with an Even Bigger Heart

Some news stops you in your tracks.

The sudden passing of Glen Roland, President of South East United Football Club, is one of those moments.

A young man taken far too soon.

A man with a family who adored him.

A football person, through and through.

And a club leader who carried more than most people will ever see.

Today, my heart is with the South East United community and most of all with Glen’s family, his loved ones and the people who will now have to work out how the world continues without him.

Because the truth is, when you lose someone like Glen, it is never just the loss of one person.

It is the loss of a whole centre of gravity.

Football is not just a game

This is one of the reasons I write.

Because from the outside, football clubs can look like something simple.

A weekend hobby.

A bit of sport.

Eleven players, a referee, some goals, a few cheers.

But anyone who has lived inside a club knows the truth.

A football club is a community.

A football club is belonging.

A football club is family.

A football club is the thing that holds people together when life is hard.

And sometimes, heartbreakingly, it is the thing that people pour themselves into right up until the end.

Glen was more than a President

South East United has shared the sad news of Glen’s passing, and their words were true.

Glen was far more than a President.

He was one of those club leaders who doesn’t just “hold the position”.

He holds the whole club.

The organising.

The worrying.

The meetings.

The emails.

The quiet planning nobody sees.

The constant pressure.

The responsibility.

And still, he showed up.

A leader driven by love

I spoke with Glen not that long ago.

And what I saw was not ego.

Not status.

Not politics.

I saw love.

He loved his club.

He loved his people.

He cared deeply about what South East United could become and what it could offer the players and families who belong there.

He was ambitious too.

He wanted South East to grow, to be taken seriously, to earn its place.

He was worried about licensing and whether the club would be granted the opportunity to step up.

That matters.

Because licensing is not just paperwork.

It is not just systems and boxes and policies.

For clubs like South East United, licensing is the difference between being told “you are welcome” or being told “you do not belong here”.

And Glen cared because he knew what that outcome would mean to his people.

That was Glen.

Ambitious, driven, determined.

But underneath it all, motivated by love.

The hidden work of volunteer presidents

Volunteer club presidents don’t get applause.

They don’t get press conferences.

They don’t get an annual wage.

What they get is the late-night phone calls.

The complaints.

The constant stress.

The weight of being the person everyone expects to fix everything.

They carry the club on their shoulders and then go home and try to be a parent, a partner, a son, a friend.

They do it out of duty and out of care.

And when that kind of person is suddenly gone, it leaves a hole that is hard to describe.

Because they weren’t just a name on a committee list.

They were the engine.

Vale Glen

It is a terribly sad day.

Glen Rowlands was a big man with an even bigger heart.

He mattered to South East United.

He mattered to Tasmanian football.

And he mattered, most of all, to his family.

To Glen’s loved ones, I am so sorry.

There are no words that can meet a loss like this, but please know that the football community feels it with you.

And to South East United, I know your grief will be deep, because your gratitude will be deep too.

Rest in peace Glen.

You will be greatly missed, but never forgotten.

Love from Ken and Victoria

Changerooms: Not a Luxury, Not Grand Designs

Letter to the Editor - The Mercury 21 January 2026

To the Editor,

The Mercury Newspaper

I write in response to the letter published in The Mercury this morning 21 January regarding the cost of upgrading changerooms at a community sporting ground.

In my view, it reflects a narrow understanding of what something as simple as a decent changeroom can mean to the people who use it.

It is not about luxury. It is about belonging.

It is about the quiet message a facility sends to every player, volunteer, coach, parent and referee who walks through the door: you are valued, you matter.

Why would we want our community spaces to send any other message?

For decades in Tasmania, community sport has been expected to “make do”. We have normalised inadequate infrastructure and learned to wear it like a badge of honour.

The truth is, we weren’t tougher. We were simply underprovided for and we got used to it.

A changeroom is not just a concrete box with a light bulb.

It is a public community space. And like any public space, it should meet modern expectations of safety, accessibility and dignity.

That matters for everyone, but especially for women and girls.

We cannot keep saying we want to grow female participation in sport while expecting women’s teams to change in outdated facilities with poor privacy, poor lighting, poor security and little regard for basic comfort.

Many people have no idea how often women and girls have been expected to change in toilets, in cars, or arrive already changed because facilities simply aren’t fit for purpose.

In 2026, sporting facilities must also support child safety and appropriate supervision, not create risk through outdated layouts, poor lighting, and inadequate design.

The same applies to volunteers.

Community sport runs on the backs of volunteers who arrive early, stay late, clean up, lock up, pick up rubbish, comfort children, manage conflict, wash bibs and organise equipment.

The least we can do is provide environments that reflect respect for their time and effort.

And for those who scoff at the cost, I would ask: what do people believe modern public buildings cost?

Construction costs have risen sharply. Compliance requirements are higher. Accessibility standards are non-negotiable. Materials must be durable, vandal resistant, safe and fit for year-round use.

This is not a “Grand Designs” fantasy.

It is what it costs to build properly, once, instead of cheaply, twice.

We rarely see this level of outrage when money is spent on projects that don’t touch community life nearly as directly.

There is also a particular Tasmanian habit of mocking improvement, as though wanting decent public facilities is somehow a character flaw.

Sport is one of the last spaces where Tasmanians still gather across generations, incomes, suburbs and backgrounds.

It gives children routine and belonging.

It builds community identity.

It strengthens wellbeing.

It provides connection, not just competition.

If governments and councils are serious about health, participation and community cohesion, then sport cannot continue to operate out of facilities built for another era, alongside attitudes that suggest we should simply be grateful for whatever we are given.

We should not be mocking changeroom upgrades.

We should be asking why community sport has been expected to tolerate neglect for so long.

Yours sincerely,

Victoria Morton

Hobart

About the author

I’m Victoria Morton. I’ve spent 20 years in Tasmanian football as a volunteer, club leader and advocate.

I’m writing a personal record of what I’ve seen, what I’ve learned and what Tasmania’s football community lives every week.

👉 Read more about me here: About Victoria

Stop Telling Football to be Grateful: Follow up- This is What ‘Apply for Grants’ Looks Like

Photo: Kingborough Lions United Facebook Page

A quick follow-up to Part 3

After publishing Stop Telling Football to be Grateful, Part 3: OMG the Money! I want to add a short follow-up.

Not to re-run the stadium debate.

Not to pick fights.

Simply to add a real-world example that landed this week that perfectly illustrates what I mean when I talk about Tasmania’s funding culture.

Sherburd Park is getting an upgrade (and that is good news)

The Tasmanian Premier, Jeremy Rockliff, announced funding for new changerooms at Sherburd Park in Blackmans Bay.

I want to say this upfront.

This is good news.

Sherburd Park has been a poor facility for a long time. I have visited it many times over the years. Anyone who has spent a wet winter afternoon there understands exactly why this upgrade is needed.

Modern, inclusive changerooms are not “nice to have”.

They are basic sporting dignity, especially for women and girls.

So yes, I’m pleased to see this happening.

What the funding actually looks like

Sherburd Park’s upgrade has been funded through the Tasmanian Government’s Active Tasmania – Active Infrastructure Grants Program.

The funding for Sherburd Park is:

$463,575 in grant funding

with the Premier stating the total co-funded investment is more than $925,000

because it is being matched by Kingborough Council

That co-contribution matters.

Because when people read “government grant”, they often imagine money simply arriving.

But that is not how it works.

A small pool, spread thin

This year’s Active Infrastructure grant pool was $5 million, split across 30 projects.

That is the entire pot.

Statewide.

Across every sport.

Across every region.

And that works out to an average of around $166,000 per project.

It is not hard to see why so many clubs have ageing toilets, unsafe changerooms, no lighting, poor storage and worn-out surfaces.

Not because clubs aren’t trying.

Because the infrastructure need massively exceeds the money available.

The hidden reality: grants require capacity (and cash)

Behind every successful grant announcement is a huge amount of work.

Quotes. Designs. Budgets. Risk documentation. Support letters. Planning. Reporting.

Need isn’t enough. Clubs and councils also need capacity.

And in community sport, capacity usually means volunteer hours.

Capacity is not evenly distributed across Tasmania.

These grants also come with requirements that quietly shape who can even compete.

The program guidelines allow grants in the range of $25,000 to $500,000 and require a minimum 20% co-contribution.

So clubs don’t just need.

They need money.

They need people.

They need time.

This is the point that never makes it into the press releases.

Football people are not just running teams.

They are writing grant applications at night.

They are chasing quotes between work and children.

They are doing governance paperwork so kids can train under a light that actually works.

And what clubs are chasing isn’t glamorous

This matters too.

Most clubs are not applying for luxury items.

They are applying for the unsexy basics:

lights

toilets

changerooms

drainage

storage

safe access

warm, dry spaces where players can get changed with dignity

The things that make weekend sport possible.

Full disclosure

Full disclosure, South Hobart Football Club applied for lighting funding in this same round and was unsuccessful.

That isn’t a complaint.

It’s simply reality.

This program is competitive because the need is enormous and the pool is limited.

The point (and why this follows Part 3)

Sherburd Park getting an upgrade is not the story.

The story is what it reveals.

A funding culture built on scarcity.

A system where clubs are expected to compete for crumbs, carry the admin burden and then be grateful for whatever they can scrape together.

It’s worth saying this clearly, before anyone turns this into the wrong argument.

Football did receive one major grant in this round and Sherburd Park deserves it.

But one successful project doesn’t change the structural reality.

Even in a round where football receives a large grant, the total statewide pool is still only $5 million.

So this is not about football trying to get everything.

It’s about a system where community life, community sport and participation are placed inside a permanent scarcity model.

And scarcity produces predictable outcomes.

Most clubs miss out.

Many committees spend months preparing applications that don’t succeed.

And the infrastructure backlog stays right where it is.

Why this matters in the AFL context

This is why Part 3 mattered.

Football is told to apply for grants.

Football is told to share.

Football is told to co-contribute.

Football is told to be grateful.

AFL doesn’t live inside that same system.

AFL gets structural investment as certainty.

Locked in money.

Large scale money.

Not “if you’re lucky”. Not “if your volunteer committee can write a perfect application”. Not “if you can raise the co-contribution”.

That is the difference.

Football is managed through scarcity.

AFL is funded through certainty.

This isn’t just football (and that matters)

One of my neighbours is heavily involved in the arts.

And they made the same point.

The arts are scrimping too.

Grants. Applications. Co-contributions. Volunteers. Small pools spread thinly across massive need.

It is the same pattern.

Community sport scrimps. The arts scrimp. Councils scrimp. Volunteers fill the gaps.

And the message is always the same:

There isn’t enough money.

But what people are really experiencing is this:

There isn’t enough money for community life.

The real question

If Tasmania is serious about participation, wellbeing, inclusion and active communities, then we need to stop pretending a small competitive grant pool is a solution.

Grants help.

But they do not fix the structural problem.

They manage it.

And they normalise scarcity.

Football people aren’t ungrateful.

They are exhausted.

They are doing the maths.

And they are done being told to clap politely while their sport is squeezed into whatever space and whatever scraps are left over.

Sources / References

Active Tasmania – Active Infrastructure Grants Program (2024–25 successful applicants list)

Premier’s media release / announcement re Sherburd Park funding

Kingborough Lions United Football Club Facebook post

About the author

I’m Victoria Morton. I’ve spent 20 years in Tasmanian football as a volunteer, club leader and advocate.

I’m writing a personal record of what I’ve seen, what I’ve learned and what Tasmania’s football community lives every week.

👉 Read more about me here: About Victoria

Don’t Swear, It’s Not Ladylike. For Fuck Sake.

You are probably wondering why I have become so noisy.

Why I have become so busy in the advocacy space.

Why I keep writing.

Why I keep speaking.

Why I keep turning up.

Why I don’t just let it go, move on, step back, enjoy the quiet life.

Some people will say I am outspoken.

Some will say I am loud.

Some will say I am difficult.

Some will say I make everything about myself.

I’ve heard it all before.

But what I am doing now is not new.

The truth is, I have always had opinions.

I have always had strong instincts about fairness.

I have always noticed who holds power, who gets listened to, who gets dismissed and who gets told to be grateful.

The difference is that now I am saying it out loud.

And that shift did not happen overnight.

It took a lifetime.

This post is not directly about football.

But it is absolutely connected to football, because sport reflects culture and football reflects culture as loudly as anything.

If you want to understand why women hesitate before speaking in meetings, why they soften every sentence, why they apologise before disagreeing, why they get labelled “emotional” or “difficult”, here is one version of that story.

Mine.

I was taught to be quiet

When I was a girl, I was told to be quiet.

Not because I had done something wrong.

Not because I was being rude.

Because I “didn’t know what I was talking about”.

It’s amazing how early girls learn that speaking is risky.

That having an opinion is something you should earn.

That the safest thing to be is pleasant and silent.

I learnt it early.

And I learnt it well.

What school trained into me

At school you had to put your hand up to speak.

Even that simple rule teaches something deeper.

You don’t speak when you think of something.

You speak when you are permitted.

You wait.

You consider whether it’s worth it.

You measure whether the room will approve.

I went to boarding school.

We were made to go to chapel.

And you had to be quiet.

Quiet was not just behaviour.

It was virtue.

Quiet meant good.

Quiet meant obedient.

Quiet meant acceptable.

The kind of quiet that keeps the peace

I got married young.

Actually, more than once.

I got married young.

Actually, more than once.

And in those marriages (not Ken, he is my wonderful number 3) I stayed quiet for the sake of happiness and peace.

Not my own.

That sounds noble when you say it like that.

But it’s not.

It’s not peace if one person is always swallowing their own thoughts.

It’s not happiness if you are constantly managing yourself so the atmosphere stays calm.

It’s compliance.

It’s self-erasure dressed up as maturity.

It’s the quiet women do to survive.

“You’re loud.” “You’re outspoken.”

All my life I was told I was loud.

Or outspoken.

As if that was a character flaw.

As if it was a warning.

As if my job was to soften, not to speak.

I look back now and realise something.

“Loud” is rarely about volume.

It’s about permission.

Women are “loud” when we stop whispering.

Women are “outspoken” when we stop editing ourselves to keep everyone comfortable.

The careful years

When I became President of South Hobart Football Club, I had to be careful.

Careful not to bring the game into disrepute.

Careful not to say the wrong thing.

Careful not to upset someone important.

Careful not to ruffle feathers.

Careful not to offend a politician who might one day decide to give us money.

Careful.

Careful.

Careful.

If you’ve ever sat in leadership as a woman, you know this feeling.

You can feel the invisible line.

Speak too plainly and you’re “unprofessional”.

Speak too strongly and you’re “emotional”.

Speak too often and you’re “dominating”.

Speak at the wrong time and you’re “difficult”.

So you learn to manage yourself.

You learn to read the room.

You learn to phrase truth like a question.

You learn to use the polite voice.

And you become very, very good at it.

I was good at it.

Weaponising speech

At a Football Tasmania AGM I was told it was all about me.

Not my points.

Not the substance.

Not what I was raising.

Me.

That line is designed to do one thing.

Shut you up.

It’s a tactic.

A way to turn advocacy into ego.

To make the person speaking the problem, instead of what they are saying.

To embarrass you in public and warn others not to align themselves with you.

It is not a rebuttal.

It is not leadership.

It is speech used as a weapon.

And I have seen that tactic used on women over and over.

Not just in football.

In meetings, in organisations, in families.

You keep speaking and instead of engaging with the issue, someone says you’re “making it about yourself”.

It is a cheap line.

It works because it creates doubt.

And doubt is often enough to silence a woman who has spent her entire life trying to stay acceptable.

The fear underneath

I was afraid to speak.

Afraid to have an opinion that seemed loud.

Afraid that speaking up would backfire.

Afraid of the consequences.

Afraid of being disliked.

Afraid of being “that woman”.

I let myself be pushed around.

I heard versions of the same message over and over.

You better not do that.

It might backfire.

What will people think?

Maybe just let it go.

Maybe don’t stir things up.

And because I was trained to seek approval, I listened.

What happens when you get older

And then something happens.

You get older.

And you stop caring.

Not in a sad way.

Not in a defeated way.

In a free way.

You stop caring if your clothes aren’t perfect.

You stop caring if you carry too much weight.

You stop caring if you say the wrong thing.

You stop caring if someone thinks you’re too much.

You stop living your life like a performance for other people’s comfort.

You stop shrinking.

You stop apologising.

You stop editing.

You stop asking permission.

And at some point, you look back at all the years you spent trying to be “good”, trying to be “nice”, trying to be “ladylike”, trying to be quiet and acceptable and palatable and manageable, and you just think:

Fuck me.

I am not available for silence anymore

This is not just my story.

It’s a story many women will recognise.

Women who were raised to be good.

To be polite.

To be modest.

To not make it about themselves.

To keep the peace.

To smooth things over.

To be grateful.

And if they ever stepped out of that role, they were called loud.

Outspoken.

Hard work.

Too intense.

Too much.

But “too much” is often just what a woman looks like when she’s finally living in full size.

I’m not interested in being quiet anymore.

Not for comfort.

Not for permission.

Not for approval.

Not for peace that only exists when I swallow myself.

I have opinions.

I have earned them.

I have lived them.

And I will say them.

Football taught me many things.

One of them is this:

Silence protects power.

Stop Telling Football to be Grateful, Part 3: OMG the Money!

Artists impression of the Macquarie Point Stadium - show me the money

Follow the money (and what Tasmania funds and what it doesn’t)

Before I get into the figures, I want to clarify something.

When I say “the Government is funding AFL”, I’m not talking about some separate, mysterious pot of money that has nothing to do with ordinary Tasmanians.

Government money is not magic money.

It’s not someone else’s money.

It is our money.

It comes from taxpayers, ratepayers, workers, business owners, parents, volunteers, clubs, communities, everyone.

Sometimes people talk about “government” as if it is a completely separate entity, floating above society, handing out favours.

But it’s not separate.

It’s us.

So when millions of public dollars go into AFL facilities, AFL programs, AFL pathways and AFL priorities, that is not “AFL getting funding”.

That is Tasmania choosing, through its elected representatives, to direct our shared money into that code.

And if you are a football person, and you pay tax and you coach and you volunteer and you fundraise and you run a canteen and you pay club fees, then you are allowed to ask:

Why does one sport receive structural investment as a certainty, while another sport is told to share space and be grateful?

That isn’t bitterness.

That’s civic literacy.

Participation (so we’re talking facts, not opinions)

Football is often treated like the noisy code that should just calm down.

But football is not small.

Football Tasmania’s published participation summary (using Football Australia reporting) states Tasmania has 31,278 football participants, including 14,552 outdoor football participants.

AFL Tasmania reporting in 2024 put total registered participation at 21,002.

Participation data is never perfect, and categories are never identical across sports, but the point is obvious.

Football is a major participation sport.

AFL is a major sport too.

But in Tasmania, only one of them is treated like it deserves serious public investment.

What the Tasmanian Government gives football (soccer)

This is the number that should stop everyone mid-sentence.

A Tasmanian Parliament Question on Notice response states the Tasmanian Government provided Football Tasmania $1.85 million from 2022–23 to 2025–26. (afl.com.au)

That’s roughly $462,500 per year (averaged across four financial years).

If you break that down using Football Tasmania’s total participation figure:

31,278 participants.

That works out to about:

$14.80 per football participant per year

That is what the baseline public investment looks like for the biggest participation sport in Tasmania.

And the rest is made up by:

volunteer labour

fees

fundraising

canteens

raffles

parents topping up what the system refuses to provide

What the Tasmanian Government gives AFL (before we even talk about a stadium)

The Tasmanian Government’s funding commitment for the AFL licence has been reported as $12 million per year for 12 years (a total of $144 million). (ABC)

That is:

$12,000,000 per year

for 12 years

locked in

Now break it down against the AFL participation figure (21,002):

That’s approximately:

$571 per AFL participant per year (afl.com.au)

So, on a straight annual comparison:

Football baseline: ~$462,500 per year (afl.com.au)

AFL licence funding: $12,000,000 per year (ABC)

That is roughly 26 times higher, every year.

Not over the long run.

Every year.

AFL’s High Performance Centre (another major public spend)

AFL funding does not stop at the licence.

Reporting has stated a $105 million cap on State funding for the AFL High Performance Centre. (ABC)

In other words, AFL gets:

direct annual licence funding

plus a purpose-built high performance facility

And football gets told to share ovals and apply for a grant.

AFL infrastructure across Tasmania (the statewide pattern)

This isn’t just about Hobart.

The AFL infrastructure investment pattern exists across Tasmania.

York Park / UTAS Stadium (Launceston)

The redevelopment of York Park has been widely reported as a $130 million upgrade, consisting of $65 million from the Australian Government and $65 million from the Tasmanian Government. (ABC)

Dial Park (Penguin)

The Tasmanian Government committed $25 million (2024–2026) for infrastructure upgrades at the Dial Regional Sports Complex in Penguin (Dial Park). (Central Coast Council)

Again, not a competitive grant.

Not “if you’re lucky”.

A structural public funding decision.

And then there’s the stadium

Macquarie Point is now being discussed publicly as a $1.13 billion stadium project.

I’m not going to re-run the stadium debate here.

But the point is unavoidable:

Tasmania can mobilise a billion-dollar project for one sport.

But football people still can’t get basic rectangular field access, lighting and changerooms that respect women and girls.

The costs don’t stop at construction

There’s another point people keep missing.

These big projects aren’t a one-off cheque.

They come with ongoing costs.

ABC reporting has pointed to the stadium having substantial operating and lifecycle cost implications, with safeguards calling for information to be released on ongoing subsidy and lifecycle costs after contractor selection. (ABC)

So this isn’t just money spent.

It’s money committed.

The totals (this is what “be grateful” looks like)

Here’s the part people hate seeing written down.

If we set the stadium aside for a moment, AFL-linked government funding and upgrades include:

AFL licence funding: $144 million (ABC)

AFL High Performance Centre (State cap/commitment): $105 million (ABC)

York Park upgrade: $130 million (ABC)

Dial Park upgrade: $25 million (Central Coast Council)

That’s $404 million in AFL-linked public funding and infrastructure, before the stadium.

And if Macquarie Point proceeds at $1.13 billion, the scale becomes something else entirely.

So when football people are told to be grateful, this is what they are being asked to accept:

AFL gets hundreds of millions (and potentially over a billion) while football fights for crumbs.

Dollars per participant (the comparison that hurts)

This is where it becomes impossible to pretend this is “equal treatment”.

Annual comparison (rough but revealing)

Football baseline public investment:

$462,500 per year for Football Tasmania (avg) (afl.com.au)

31,278 participants

= ~$14.80 per participant per year

AFL licence funding public investment:

$12,000,000 per year (ABC)

21,002 participants

= ~$571 per participant per year

That’s not a small gap.

That is a policy decision.

Twelve-year comparison (so no one can argue “short term”)

Over 12 years:

AFL: $144m / 21,002 ≈ $6,857 per participant over 12 years (ABC)

Football baseline: $1.85m over 4 years = ~$5.55m over 12 years

$5.55m / 31,278 ≈ $177 per participant over 12 years (afl.com.au)

Read that again.

Over the same time period:

AFL: $6,857 per participant

Football: $177 per participant

And that’s still before HPC, York Park, Dial Park, or the stadium.

The grant myth (the rigged part nobody admits)

This is where football people start to feel like they’re going mad.

Because yes, football can apply for grants.

But so can AFL.

So AFL gets:

direct government funding at scale

elite facilities and upgrades as a default

and then still competes for the same grant pools community sport is forced to fight over

Football gets:

a tiny baseline allocation (afl.com.au)

the same competitive grant pools

minus the spare volunteers and spare time required to survive constant applications just to stand still

That is not an even playing field.

That is stacking advantage on advantage.

Why this matters (and why I’m done being polite about it)

This is not an anti-AFL post.

People can love AFL.

People can play AFL.

People can attend AFL matches.

The issue is not AFL existing.

The issue is Tasmania’s funding culture, where prestige sport receives investment as a certainty…

…and participation sport is treated like a problem to manage.

Football people aren’t ungrateful.

They are exhausted.

They are doing the maths.

And they are done being told to clap politely while their sport is squeezed into whatever space is left over.

Stop telling football to be grateful.

About the author

I’m Victoria Morton. I’ve spent 20 years in Tasmanian football as a volunteer, club leader and advocate.

I’m writing a personal record of what I’ve seen, what I’ve learned and what Tasmania’s football community lives every week.

👉 Read more about me here: About Victoria

Sources / Bibliography

Tasmanian Parliament, Question on Notice: Government funding provided to Football Tasmania (2022–23 to 2025–26), total $1.85m (afl.com.au)

Football Tasmania participation summary (Football Australia reporting): 31,278 participants (incl. outdoor, futsal, schools)

AFL Tasmania participation figure: 21,002 registered participants (2024 reporting)

ABC News (19 Sept 2022): Tasmanian Govt increased AFL licence funding offer to $144m over 12 years (ABC)

AFL.com.au (Nov 2022): In-principle agreement notes Tas Govt commitment includes $12m/year over 12 years (and HPC funding) (afl.com.au)

ABC News (3 Dec 2025): Stadium bill safeguards include $105m cap on state HPC funding; lifecycle/ongoing subsidy info (ABC)

AFL.com.au (13 Aug 2025): State contributing $105m to high performance centre (afl.com.au)

ABC News (28 Apr 2023): York Park upgrade includes $65m federal + $65m Tasmanian Govt (= $130m total) (ABC)

Central Coast Council (14 Mar 2025): Tas Govt committed $25m (2024–2026) for Dial Park upgrades (Central Coast Council)

Tasmanian Infrastructure: Dial Park major project info (Infrastructure Tasmania)

Macquarie Point stadium cost publicly reported as $1.13b

Stop Telling Football to be Grateful - Part 2 - Who Heard Us, and Who Didn’t

Who replied, who didn’t, and what that revealed

Before the Upper House vote on the Macquarie Point stadium, I wrote to every Member of the Legislative Council.

Not as a politician.

Not as an activist.

Not as part of a pro-stadium or anti-stadium machine.

I wrote as a football person.

A grassroots football person. A volunteer. A parent. A club president. A junior association president. Someone who represents thousands of families who spend their weekends doing what Tasmania always claims to value.

Showing up. Pitching in. Holding the line.

In Part 1, I said this wasn’t about the stadium.

That is still true.

This series is about what the stadium debate exposed.

Because once you strip away the politics, the press conferences and the slogans, one message kept coming through loud and clear to Tasmanian football people.

You are expected to stay quiet.

And if you do speak up, you’re expected to do it politely.

And if you keep going, you’re told you should be grateful.

Part 2 is about correspondence.

Who replied. Who didn’t. And what was revealed in the silence.

Who I wrote to

I wrote to every Member of the Legislative Council, regardless of party.

Football families don’t live in one electorate or vote in neat little blocks.

We are everywhere.

We are the sport that fills the weekends, fills the grounds, fills the car parks, fills the volunteer rosters and still somehow gets treated like we should wait our turn.

Who replied (and how)

This is the list, as accurately as I can make it from my inbox.

Thoughtful reply

Megan Webb (Independent), reply received

Rebecca Thomas (Independent), reply received

Ruth Forrest (Independent), reply received

Michael Gaffney (Independent), reply received

Dean Harriss (Independent), reply received

Reply received (Minister)

Nick Duigan (Liberal), reply received

Acknowledgement only, or triage reply

Rosemary Armitage (Independent), acknowledgement only

Joanne Palmer (Liberal), acknowledgement only

Tania Rattray (Independent), electorate priority or office triage response

Cassy O’Connor (Greens), acknowledgement only

No reply received

Luke Edmonds (Labor), no reply

Craig Farrell (Labor), no reply

Casey Hiscutt (Liberal), no reply

Sarah Lovell (Labor), no reply

Kerry Vincent (Liberal), no reply

That’s the pattern.

Not “all bad”. Not “all good”.

But a pattern.

And when you represent thousands of families who already feel invisible in decision-making, patterns matter.

The “thousands of emails” factor

I also want to acknowledge something else, because fairness matters.

Several MPs said they received thousands of emails about the stadium. One MLC told me directly they had received over 3,000 pieces of correspondence. Another office advised that because of the volume, they prioritised replies only to people who live inside their electorate.

I understand that workload pressure is real.

But it is also revealing.

Because football families don’t stop mattering at electorate boundaries. And when a grassroots sport representing tens of thousands of Tasmanians is raising a structural fairness issue, “sorry, too many emails” is not an answer.

It might be an explanation.

But it is not an answer.

The line that made my blood boil

Only one response raised the point that football has already received grants.

It wasn’t framed as a reprimand, but it carried the same implication.

That football should accept what it gets and move on.

That is exactly the culture I’m pushing back against.

You’ve received grants already.

You’ve had funding.

You’ve gotten something.

In other words.

Stop complaining. Be grateful.

That is the culture I’m calling out.

Because “you’ve received grants” is not an argument.

It is a silencing tactic.

It’s the logic you would use on a community group running a bake sale, not the largest participation sport in Tasmania.

It turns football into a charity case and casts its volunteers as ungrateful whenever they insist on fairness.

Grants are not fairness

Let’s be very clear.

Grants are not the same thing as equitable investment.

Grants are not policy.

Grants are not planning.

Grants are not infrastructure strategy.

Grants are not long-term development.

Grants are not fairness.

Grants are often what governments do when they want to look supportive without making structural commitments, and when they want community sport to keep scraping and scrambling, competing with each other for crumbs.

And football families are sick of it.

We are sick of being told we’re “lucky” to receive a one-off grant while other sports receive major, sustained, strategic investment built into the long-term planning of the State.

We are sick of being told we should smile and say thank you.

That’s not respect.

That’s containment.

This is not personal

I want to say something clearly here.

This series is not about attacking individuals.

Some people replied thoughtfully. Some engaged properly. Some clearly tried to balance competing priorities.

And I respect that.

I also want to be clear about this.

I do not want to work against people who have supported football or genuinely engaged with the issue. Tasmania is too small for scorched earth politics. Good governance requires honest relationships.

But honest relationships also require honest truths.

And one honest truth is this.

Football people are repeatedly treated like we should accept whatever we are given, quietly.

The silence is also a message

The no-replies matter.

Not because every MP is obliged to agree with me.

Not because I’m entitled to personal attention.

But because football families were polite, factual, and measured.

We raised participation numbers.

We raised fairness and equity.

We raised infrastructure shortages.

And still, many were met with silence.

That silence reinforces exactly what football families already feel.

We are seen as background noise.

We are not seen as a priority.

We are expected to keep functioning anyway.

And the reason we keep functioning is not because the system supports us.

It’s because volunteers do.

A fair go

Tasmania loves a few phrases.

“A fair go.”

“Pub test.”

“Common sense.”

So let’s apply that here.

If the biggest participation sport in the State is still short of basic rectangular facilities, still overcrowded, still squeezed, still sharing, still training in the dark, still fighting for ground space, still treated like it should be grateful for scraps.

Does that pass the pub test?

Does that feel like a fair go?

What happens next

In Part 3, I’m moving away from correspondence and into the numbers.

Because this argument is not emotional.

It is measurable.

Participation.

Facilities.

Infrastructure.

Public spending.

And the opportunity cost paid by every other sport, every weekend, in mud, darkness and over-crowded rosters.

Football is not asking for special treatment.

Football is asking for what every other code would demand in our position.

A fair reflection of our size, our load and our contribution to Tasmanian community life.

Part 3 is where the numbers begin.

And once you see them, it becomes harder to pretend this is just football people “whingeing again”.

Stop Telling Football to Be Grateful - Part 1.

Before the Upper House vote on the Macquarie Point stadium, I wrote to every Member of the Legislative Council.

Not as a politician.

Not as an activist.

Not as part of a pro- or anti-stadium machine.

I wrote as a football person.

A grassroots football person. A volunteer. A parent. A club president. A junior association president. Someone who has watched thousands of Tasmanian kids pull on boots every weekend and has also watched those same kids train on paddocks that would embarrass us if they were in any other state.

I wrote because I’m tired of football (soccer) being treated like a side issue.

And I wrote because I knew what was coming.

The vote has now passed.

The legislation is done.

The stadium will proceed.

But this blog isn’t about the stadium.

This blog is about what happened around it.

What was revealed during it.

And what Tasmanian football families are expected to accept, quietly, politely, gratefully.

What I wrote about

My message was simple.

Football is Tasmania’s most played team sport.

We are not asking for billions.

We are asking for fairness.

Funding should reflect participation and community impact.

Not tradition.

Not political convenience.

Not which code has the biggest lobby.

And certainly not some vague promise that football will “benefit later” if we just stay patient.

We’ve been patient for decades.

Who replied

Some did reply.

Some did not.

Some replied thoughtfully, and I genuinely appreciate that. Not because it made me feel better, but because it showed respect for the people I represent.

A few replies stood out because they exposed the pattern.

One MLC asked if he could refer to my email in Parliament

That was Michael Gaffney (MLC, Mersey).

He wrote to me before the debate and asked if I was comfortable for him to reference my email in his speech.

That matters.

Because it means the message landed.

It means football’s argument was heard.

And it means that, at least for some, the issue wasn’t dismissed as emotional noise.

I want to be clear about something.

This series is not about attacking individuals.

But here’s the part that made me see red.

More than one response - explicitly or implicitly - carried the same message:

You’ve received funding already.

You’ve had grants.

You’ve gotten something.

In other words:

Stop complaining. Be grateful.

That is the culture I am calling out.

Because “you’ve received grants” is not an argument.

It’s a silencing tactic.

It’s a way of turning community sport into a child at the grown-ups table, being told to stop making noise because someone slid them a biscuit earlier.

Football is not asking to be treated like a charity case.

Football is asking to be treated like a mainstream sport.

Stop telling football to be grateful

If football is the sport with the largest participation footprint in Tasmania, why are we still begging for rectangles?

Why do we still have clubs sharing the same tired facilities year after year while huge public investments are made elsewhere?

Why are we still told to “apply for grants” like that is the answer?

Grants are not policy.

Grants are not planning.

Grants are not equity.

Grants are often what governments use when they want to look supportive without making any structural commitments.

And football families are sick of it.

A note on the ugliness

I also want to say this clearly.

The abuse directed at MPs during this whole debate has been ugly and unacceptable. I know at least one MP has locked their Facebook profile because of the backlash.

That is not leadership.

That is not civic debate.

That is not Tasmania at its best.

You can oppose a decision without tearing people to shreds.

Why this is my first blog series

I am writing this as the first blog in a series because there is too much to say in a single post.

The deeper you go into sporting investment in Tasmania, the more uncomfortable the numbers become.

Not feelings.

Not vibes.

Not “football people whingeing again”.

Numbers.

Participation.

Facilities.

Infrastructure.

Public spend.

And the opportunity cost paid by every other sport, every weekend, in mud and darkness and overcrowding.

Football is not asking for special treatment.

Football is asking for what every other code would demand in our position:

A fair reflection of our size, our load, and our contribution to Tasmanian community life.

In the next post, I’m going to move from correspondence to facts.

Because this argument is not emotional.

It is measurable.

And it is long overdue.

Marina Brkic, Glenorchy Knights FC: Mud, Bonfires and Making it Happen

Photo credit: Lisa Creese

This Football Faces interview was originally done in 2022.

In football, two years can feel like ten. Coaches move on. Committees turn over. Programs change names. Roles evolve. People take a step back, or step up.

So yes, a few details in this interview may have shifted since it was first written. But the story underneath it hasn’t changed, a life spent in the game, a club carried by volunteers, and that familiar combination of mud, bonfires, chips, and doing whatever needs doing.

That’s why I’m republishing it now.

Marina Brkic, Glenorchy Knights FC: Mud, Bonfires, and Making It Happen

There are football people you notice because they are loud.

And there are football people you notice because they are everywhere, doing everything, holding everything together, usually without a fuss.

Marina Brkic is one of those people.

A Glenorchy Knights stalwart. A long-time player. A club official. A coach. A team manager. A social media machine. A youth team driver. A volunteer. A mother of three football boys.

Still playing herself, and loving it.

When I look back over the last couple of decades of Tasmanian football, faces like Marina’s are the ones that stand out. Not because they chase attention, but because they are always there, still doing the work.

This interview was done a couple of years ago, but it still rings true. It’s the kind of story that belongs on the record.

First football memories

Marina’s first football memories are not polished, glamorous, or Instagram-friendly.

They’re real Tasmanian football memories.

Doing the scoreboard at KGV with her sister, paid in the most authentic grassroots currency possible, a packet of chips and a drink.

Standing in the mud next to the bonfire while the games rolled on.

If you’ve been around long enough, you can smell that sentence.

That’s football.

Not elite. Not high performance. Not “pathways”.

Just people, cold hands, smoke in your hair and a community built around the game.

A life in football

Marina doesn’t just say she’s been around football forever.

She has.

Her dad took her to watch Croatia-Glenorchy from early on. The game was in her bones before she could properly name it.

She’s been involved for most of her life, playing for 30 years, starting with Raiders and DOSA, but with most of that time spent with Glenorchy Knights. That sort of loyalty is not as common as it once was and it matters.

Along the way she has also taken on the roles that clubs rely on:

Coach.

Team manager.

Committee member across various roles for 20+ years.

And now she’s club secretary, part of the executive, manages social media, manages a youth team, and “many other things” (which is volunteer code for too many things).

And as if that wasn’t enough, she has three boys who all play at the club, too.

This is what football looks like when you live it properly.

What Tasmania’s football used to feel like

One of the striking things Marina remembers is senior men’s football crowds.

Big crowds.

That atmosphere has faded in many places and I think most of us can admit it. We can debate why, we can blame a dozen things, but the shift is real.

Marina also points out something important about female football, girls her age simply were not encouraged to play. She was a late starter because of that cultural barrier.

And yet she’s spent years doing the opposite for the next generation.

She has pushed female football at her club and beyond it. She speaks with real pride about seeing lots of girls playing now in junior and youth teams and she notes that the quality and support for female football has improved.

That’s not an abstract achievement.

That’s a direct outcome of people like Marina doing hard work over a long time.

Heroes, anti-heroes, and what actually matters

Marina doesn’t go looking for celebrity football heroes.

She values something different, and it’s a quiet lesson in what club culture is built on.

Hard-working.

Reliable.

Club loyal.

Respectful.

She’s met plenty of those people along the way, and that’s what she appreciates.

No drama.

No ego.

No hype.

Just the people you can count on.

The ones who make football happen.

Football and family: the reality

People underestimate how much football takes from a family when someone becomes deeply involved in running a club.

Not playing.

Running it.

Marina is honest about that.

She talks about the impact on personal time. The work. The load. The constant demands. The unspoken expectation that you will simply keep doing it.

But she also says what makes it worth it.

Her whole family loves the game.

There are lows, but the highs are shared, and those shared highs are the reward that keeps you going.

I also loved her line about being supported to play herself. Especially when her children were young, it’s not easy. Someone has to hold the home, manage the logistics, make it possible.

Because women in football are often expected to sacrifice the playing part first.

Marina didn’t.

And that matters.

If she could change Tasmanian football

This answer should be printed and pinned to a wall in every governance meeting.

Marina’s view is shaped by time on the ground as a club official. She’s not theorising. She’s speaking from the trenches.

She says the demands on clubs have increased significantly and are about to increase further.

That’s the warning line.

And she makes it clear, any change that makes football easier for clubs, mostly run by volunteers with day jobs, would be welcomed.

Then she gets practical.

Not ideological. Not fluffy.

Rostering.

She points out that teams playing in different locations stretches club resources. It impacts the matchday experience. It chips away at club culture.

So she calls for something simple and sensible, consistent rostering of teams together.

It’s the kind of idea that doesn’t make for a glossy strategy document, but makes an immediate difference to actual volunteers.

That’s the kind of thinking Tasmanian football needs more of.

Her legacy

Marina doesn’t claim a grand legacy.

She says something much more accurate.

All clubs have committed and hard-working people that make it happen.

Her legacy is that she’s one of those people.

And then she finishes with humour, saying she would have liked to have scored more goals over the years, “no legacy there lol!”

That made me laugh because it’s exactly the kind of line football people write when they’ve been through enough seasons to know what really matters.

Legacy is not medals.

Legacy is being there, doing the work, shaping the culture, and helping the club survive and thrive across generations.

That is what Marina has done.

And she’s still doing it.

FOMO Isn’t Development: The Small State Pathway Problem

In a big state, a pathway program can be an option.

In a small state, it becomes a verdict.

And that is the beginning of the problem.

Tasmanian football has spent years living in the tension between club football and Federation programs. The tension isn’t personal. It’s structural.

In a small state, there isn’t enough “air in the room” for competing priorities, competing calendars and competing identities.

We don’t have the scale.

So the minute a Federation program expands, club football feels the pressure.

Not because clubs fear standards.

But because clubs fear becoming second best in the system they built.

Big States and Small States Are Not the Same

A one-size-fits-all pathway model doesn’t work in Australian football.

Not because small states lack ambition, or talent.

But because small states don’t have scale.

In Victoria and New South Wales, a pathway program sits inside a crowded ecosystem. There are huge player pools, many clubs, multiple development environments and multiple chances to be seen.

In Tasmania, the ecosystem is tight.

When one program is elevated, everything else is pushed down.

In a big state, missing one camp is inconvenient.

In a small state, missing one camp feels like a risk.

And that changes everything.

FOMO Is Not Development

One of the most damaging effects of small-state pathways is the pressure it places on children and families.

Kids should not have to live in a permanent state of football anxiety.

They should not have to agonise over every decision, wondering:

Will I be overlooked if I don’t go?

Will I be seen as not committed?

Will I fall behind?

Will I be quietly crossed off a list?

That isn’t high performance.

That is fear, pressure, and FOMO dressed up as opportunity.

It can quietly drain the joy out of football, and joy matters, because joy is what makes children return.

The Communication Gap Is Where Trust Breaks

The relationship between Federations and clubs in small states is fragile. It needs care, respect and communication.

Clubs plan training. Coaches volunteer their time. Parents organise work and family life around sessions.

Then suddenly a pathway event appears.

Not always with meaningful notice. Not always with coordination. Not always with a shared calendar that respects club environments.

Club coaches turn up to training and discover half their players are missing.

It doesn’t feel like partnership.

It feels like clubs are expected to comply.

Small-state football cannot survive on assumptions. It needs genuine two-way communication and planning that treats clubs as part of the solution, not an afterthought.

Clubs Aren’t Even Kept in the Loop

As a club President, I was often asked by parents simple, reasonable questions.

When are the TSP trials?

When are the Academy sessions?

What do we need to do to be considered?

And I would have to answer honestly.

I had no idea.

Not because I wasn’t paying attention and not because the club didn’t care. I didn’t know because Football Tasmania did not share that information with clubs.

That is not a minor communication gap.

That is a relationship gap.

It forces clubs into an awkward position, standing in front of families with no information about a program that is clearly influencing selection and opportunity.

It makes clubs look uninformed.

Worse, it makes clubs look irrelevant.

And in a small state, that matters.

Secrecy Creates Suspicion

Football Tasmania may be trying to improve communication now and if they are, that is welcome.

But when key information is kept quiet, the message it sends is not neutral.

It tells clubs that this information is not for them.

It makes it feel secretive, like something clubs shouldn’t know about, just in case clubs tell kids:

Don’t bother.

It’s a waste of time.

That may not be the intent, but it becomes the perception.

And perception shapes trust.

Acronyms Come and Go, Clubs Remain

Then there’s the churn.

We had SAP licensing requirements and then SAP disappeared.

So what will be next?

What will be the next acronym?

What will be the next “must do” program?

And when it vanishes, what happens to the kids, the parents and the clubs that rearranged everything around it?

This constant cycle of programs and terminology might look like progress from the outside.

But from inside a small-state football ecosystem, it often feels like instability.

Clubs need clarity, consistency and partnership, not the next vanishing pathway.

If Clubs Feel Second Best, The Whole System Weakens

Clubs are not the lower tier.

Clubs are the foundation.

Clubs are where habits are built, confidence is built, resilience is built, belonging is built and love of the game is built.

In small states, weekly club football is not separate from development.

It is development.

So when clubs feel like the second-best option, the culture deteriorates.

And once you lose culture, you don’t build it back by running another camp.

Do These Programs Actually Improve Results?

This is the question nobody likes being asked.

When I first came to football, the process was simple.

A coach would pick their squad. They would train together in the six weeks leading into National Championships, then they would go away and play.

It wasn’t perfect.

But clubs weren’t constantly inconvenienced.

Kids weren’t forced into a permanent cycle of fear of missing out.

Families weren’t juggling endless competing commitments.

And the results?

From where I stand, the results were similar.

So the question is fair, and it is unavoidable.

Do the current Football Tasmania programs lead to better results at National Championships than the method used back then?

If the answer is no, or even “not much”, then the next question matters even more.

If outcomes are broadly similar, why is the cost to clubs so much higher?

The Spreadsheet Would Tell the Truth

If we really want to understand why big states dominate national championships, we should put the politics aside and open Excel.

Make a spreadsheet.

One column is the number of registered players in each state.

The next column is national championship performance.

The pattern will not be surprising.

Bigger states have bigger talent pools. More depth. More competition. More specialist coaching environments.

They will almost always produce stronger squads, because they are drawing from a larger pool.

This is not an insult to small states.

It is the mathematics of scale.

Which leads to an honest question.

If a small state cannot out-number the big states, why are we pretending it can out-program them?

Small States Improve By Multiplication, Not Extraction

This is the heart of it.

In small states, the most powerful development tool is not selection.

It is coaching.

One expert coach can mentor ten club coaches.

Those ten coaches can improve hundreds of children.

That is the multiplier effect.

And it exposes a flaw in the current way we think about “development”.

If we funnel time, energy and resources into centralised programs for a small group of selected players, we might improve those players.

But we do not lift the system.

We do not lift the clubs.

And clubs are where most children will spend most of their football lives.

Imagine If That Funding Went Back Into Clubs

Imagine if the funds spent administering and delivering repeated pathway programming were redirected into club support.

Not symbolic support.

Real support.

Support that makes clubs better at what they do every week.

Support that invests in the people doing the work.

Support that reduces volunteer load rather than adding to it.

For example:

embedded technical mentoring for club coaches

subsidised coaching licences

structured curriculum support

coach education delivered inside clubs

practical planning and administration support

coordinated calendars that respect club training environments

That is how you lift a small state.

Not by creating parallel programs that compete for the same children.

Football Tasmania’s Most Important Job

In a small state, the Federation’s job is not to become the biggest and most important provider.

It is to strengthen the clubs who carry the game.

That is not glamorous.

It doesn’t always photograph well.

But it is the only strategy that works.

Because small states don’t have room for competing pathways.

They have room for one ecosystem.

And the clubs are not an optional extra in that ecosystem.

They are the system.

Women’s Football: “But No One Comes to Watch”

This week Professional Footballers Australia (PFA) released a 39-page document titled Ready for Takeoff.

It’s a long document.

But the message is simple.

Australian women’s football is at a Rubicon moment again and the A-League Women needs to relaunch as a fully professional competition, using the upcoming Women’s Asian Cup as the springboard.

Not someday.

Not slowly.

Now.

The paper makes one key argument that applies far beyond the A-League.

Progress is itself the product.

Women’s football will not grow through slogans or marketing.

It will grow when the sport embodies the advancement of women athletes.

That means standards.

And if that feels relevant nationally, it should feel even more relevant here in Tasmania.

Because in local football, standards aren’t theoretical.

They show up in the smallest details.

And they shape the whole experience.

Progress is not a vibe

There is a habit in sport of treating women’s football as something that can be marketed into importance.

A new logo.

A new campaign.

A few nice words.

But women’s football audiences can smell tokenism immediately.

Progress is not a vibe.

Progress is practical.

Progress looks like:

the same training opportunities

the same access to facilities

the same seriousness in matchday presentation

coaching standards that are not negotiable

a league structure that matches the words “elite competition”

You cannot market your way out of low standards.

“But no one comes to watch”

I remember being in a Presidents meeting years ago discussing the idea of charging a gate for women’s football.

Someone said it casually, as if it was a final truth.

As if crowd numbers were the test women’s football had to pass before it deserved standards.

I didn’t see that as the point then.

I don’t see it as the point now.

Because in women’s football, crowds are not the starting point.

Standards are.

Crowds don’t come first

If you want people to treat something like a serious product, you have to treat it like a serious product first.

Women’s football doesn’t grow because someone waited patiently for the crowd numbers to justify investment.

It grows because leadership decided the product was worth backing.

This is the loop women’s football keeps getting trapped in.

Women’s football won’t draw crowds until it looks serious.

But it won’t be treated as serious until it draws crowds.

Standards are the circuit breaker.

The gate is not just money

At South Hobart, we charge a gate for women’s games.

Some people argue they shouldn’t have to pay.

They say they’ve never had to pay before.

But what that really reveals is this.

Women’s football has never been valued properly before.

A gate is not just a fundraiser.

It is a signal of value.

A gate says:

This match matters.

This competition matters.

This is elite sport in this state.

Set the standard.

Raise the bar.

Celebrate the product.

The quiet hypocrisy

There are people who sneak in before we are even set up, just so they don’t have to pay.

They will talk about supporting the women’s game.

Then they won’t hand over $12 at the gate.

To me, that is totally pathetic.

Not because the club needs their $12.

But because it exposes what they really believe women’s football is worth.

If you can’t pay $12 to watch women athletes competing at the top level of the state game, then your support is performance, not principle.

Classification drives standards

This conversation connects directly to one of the most important issues in Tasmanian women’s football.

Women have not always been classified and treated the same as men.

Here is the truth.

If the women are not classified as NPL, they are not treated as NPL.

Classification is not symbolic.

It is a lever.

It creates:

minimum standards

compliance expectations

resourcing decisions

matchday requirements

seriousness in delivery

When standards are optional, women’s football becomes optional.

And optional always means last.

Women’s football cannot grow on leftovers

In community football, inequality rarely arrives as policy.

It arrives as default.

It shows up in hundreds of small decisions.

Later training times.

Smaller spaces.

No full-sized goals.

Facilities that are “good enough”.

Then months later, someone asks why more people aren’t watching.

That isn’t analysis.

That is sabotage.

Local football is nuanced

Sometimes inequity is not malicious.

Sometimes it is simply invisible.

I remember complaints coming to me as President that could have been fixed instantly if someone had spoken earlier.

No full-sized goals.

No access to a full field.

Sorted.

Often with one conversation.

But sometimes those concerns arrive months later.

And by then, you’re not fixing a problem.

You’re repairing trust.

Silence becomes a survival strategy for many women.

But silence is expensive.

Why FT hesitates to call it NPL

Calling the women’s competition NPL is not just a label change.

It changes everything.

NPL triggers standards.

Standards trigger consequences.

Once you attach the NPL badge, you are promising minimum expectations around facilities, training access, coaching quality, and matchday professionalism.

That means compliance.

And compliance means enforcement.

Enforcement means saying no.

Some clubs would not meet the standards.

So the governing body has to choose.

Lift standards and enforce them.

Or keep standards negotiable.

Negotiable standards allow everyone to say they support women’s football without ever having to prove it.

That is the blunt truth.

A fair note on volunteers

Volunteer clubs are stretched.

People are tired.

Raising standards does increase workload.

That is real.

But this is exactly why the governing body has to return to basics.

Not by charging clubs more each year.

But by actually helping them lift standards.

Practical support.

Clear templates.

Shared services.

A governing body that serves, not just administers and invoices.

“The way it has always been” is not an argument

This is the most common defence in football.

Someone challenges the standard.

The reply is tradition.

But tradition is not a reason.

It is a habit.

And women’s football has spent decades on the wrong end of convenience.

If Tasmanian football wants women’s football to grow, it must be built through standards.

Not excuses.

Progress is the product

The PFA paper is national.

But its logic applies everywhere.

Progress does not happen because we post the right graphic.

Progress happens when we act like women’s football matters.

On the field.

Off the field.

In facilities.

In standards.

In classification.

Women’s football is already good enough.

What’s missing is the will.

When the Pathway Breaks

I woke up this morning to the kind of football news that lands like a thud.

Not a result.

Not a rumour.

Not a coaching change.

Administration.

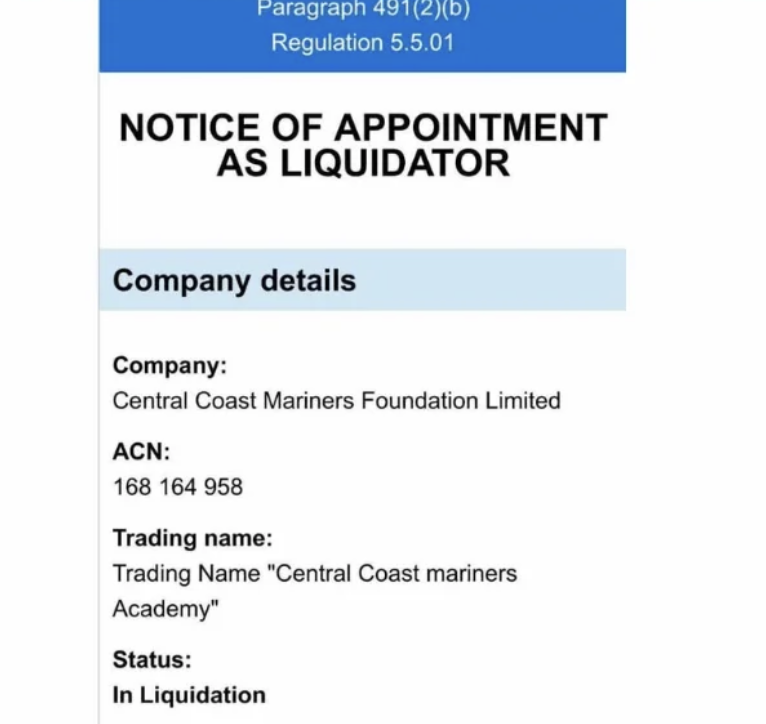

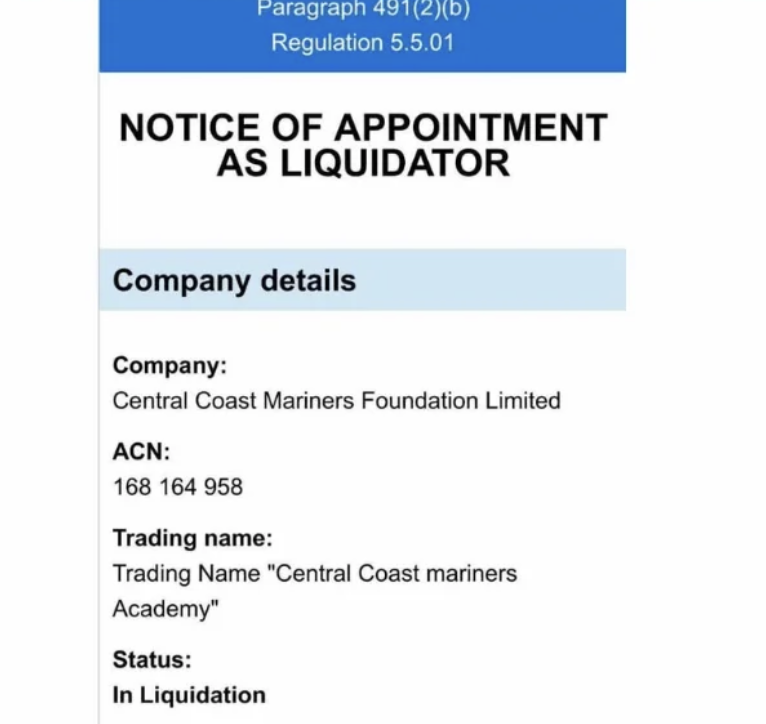

The Central Coast Mariners academy has been placed into liquidation.

Western United has been fighting for its survival.

Two clubs in the A-League system, both shaking at once.

And the story most people will tell is the business story.

Debt.

Governance.

Ownership.

Stability.

Sustainability.

But that isn’t where my mind goes first.

My mind goes to the children.

My mind goes to the parents.

Because they are the ones who live inside the dream.

And when the dream collapses, it doesn’t collapse gently.

The pointy end of the pyramid

Australian football is a pyramid.

Grassroots at the base.

Clubs and associations holding up the middle.

NPL and state leagues building the structure.

And at the top, the A-League.

That pointy end is the dream.

It is the finish line kids can picture.

It is the summit parents cling to when they are driving in the dark to training, packing lunches, paying fees and watching their child give everything.

Academies exist because the dream exists.

They are the bridge between hope and reality.

They are the part of the pyramid that tells children: this could be you.

And for the families who are inside A-League academies, it stops being a concept.

It becomes their life.

Tasmania sits outside the summit

And to be clear, Tasmania doesn’t even have an A-League team.

We are not part of that top layer and realistically won’t be.

So for Tasmanian kids, the pyramid is not just narrow at the top — it is also distant.

The “pointy end” sits across Bass Strait.

It exists in a different weekly ecosystem of eyeballs, metrics and opportunity, where scouts watch, data accumulates and pathways are visible in real time.

Here, we build our football in the margins.

We produce talent and we lose talent.

We ask families to commit and then, if a child is good enough, we often ask them to leave.

That’s the Tasmanian truth.

And it makes the instability at the top of the pyramid even harder to stomach, because the dream already asks more of our kids than it asks of most.

What A-League academy life actually looks like

A-League academy football is not “extra training”.

It is a lifestyle.

It is early mornings, long commutes, gym programs, recovery sessions, injury management, physio, school juggling, fatigue.

It is families rearranging work rosters.

It is holidays planned around football calendars.

It is birthday parties missed.

It is the quiet intensity of teenagers trying to behave like professionals.

And most of all, it is belief.

Belief that it is worth it.

Belief that the system is real.

Belief that the pathway is stable.

Because families don’t commit like this if they think the pyramid can simply fall down.

A note on where I sit in this

I write this fully aware of my own position in the system.

Morton’s Soccer School provides the coaching program for South Hobart and we charge fees, because coaching, grounds, equipment and administration all have real costs.

But philosophy matters.

Our role is not to sell professional dreams to children.

Our role is to help kids love football, train in a quality environment and stay in the game for decades, whatever level they eventually reach.

When the adults fail, the kids pay

Here is the part that is hardest to sit with.

The people running the top of the pyramid are adults.

They make adult decisions.

They take adult risks.

They build business models, chase licences, sign deals, borrow money, spend money.

But the ones exposed when it collapses are not the adults.

It’s the kids.

The academy kid who has built their identity around being “on the pathway”.

The teenager whose confidence rises and falls with selection.

The quiet hard worker who is not the star but is hanging on.

The goalkeeper who knows there are only two positions on the team, and one mistake can erase them.

The parents who have poured years into this.

Time.

Money.

Energy.

Hope.

And then it’s gone.

Not because of performance.

Not because of injury.

Not because they weren’t good enough.

Because the adults above them couldn’t keep the structure standing.

That is a different kind of heartbreak.

I’ve heard what this sounds like from the inside

I know a little about this because my son, Max, has coached in both the Melbourne City and Western United academy systems.

I have heard his stories.

I have listened to the pain and indecision from players who genuinely don’t know what to do.

Because the choices they face aren’t normal football choices.

They are career gambles.

Stay at Western United and risk missing another opportunity somewhere else, but hang on to the professional dream.

Or step back into NPL, find stability, even get paid to play football… but maybe miss the one opportunity that matters.

The one trial.

The one contract.

The one moment when a coach sees you and thinks: yes.

That is the cruelty of it.

Young players are forced to gamble with their own futures.

Not because of their attitude.

Not because they aren’t good enough.

But because the adults above them have built a system where the dream can collapse without warning.

And these are teenagers trying to make adult decisions with no safe answer.

The scramble for 2026

This is the reality nobody says out loud.

Season 2026 is now a scramble.

Families will be chasing alternatives.

Players will be looking for placements.

Parents will be sending messages, making calls, searching for opportunities.

And it won’t be neat.

Because there are only so many spots.

Only so many squads.

Only so many coaches.

Only so many programs.

And when A-League academy players flood into the market, the impact doesn’t stop with them.

It ripples outward.

Kids already in NPL teams may be pushed down.

Some may be pushed out.

Some will lose minutes.

Some will lose confidence.

Some will quietly quit.

Not because they hate football.

But because football has stopped loving them back.

This is what people miss when they talk about “pathway reform”.

It isn’t just the academy kids who get hurt.

It’s every kid underneath them too.

It makes me relieved we don’t have an A-League team and this can’t happen in Tasmania.

The pathway becomes pressure

A-League academies are supposed to develop players.

But at times they also create something else.

Pressure.

Adult pressure, applied to children.

Selection.

De-selection.

Rankings.

Benchmarking.

Constant comparison.

A belief that the next session matters more than joy.

A belief that a child’s value is measurable, sortable, replaceable.

And now, with clubs collapsing and academies destabilised, the pressure becomes heavier.

Because the pathway no longer feels hard.

It feels unsafe.

It feels like the ground can move beneath you even when you are doing everything right.

That is not sport.

That is stress.

These are children

This is where I keep coming back to the simplest truth.

These are children.

Football should be fun.

Not easy.

Not soft.

Not without disappointment.

But fun.

Because fun is what keeps people in the game for decades.

Fun is what creates lifelong players.

Fun is what builds adults who still love football at 30, 40, 50, 60.

And if football is not fun, if football becomes something children dread, something that makes them anxious, something that makes them feel disposable, then we are doing it wrong.

Because children do not have the emotional armour of adults.

They carry their failures differently.

They internalise rejection.

They confuse de-selection with worth.